TL;DR–Heavy timber served as both venue and motivator for Mosby and his men.

In April of 1864, Moby Dick author Herman Melville—by then an expert chronicler of American tumult—accompanied his friend, Col. Charles Russell Lowell of the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry, on a reconnaissance in force against Mosby from the Federal stronghold at Vienna.1

Two years later, Melville published an epic poem account of the raid. “Scout Toward Aldie” wove a narrative from threads familiar to readers of the author’s other work. Brave, but anxious men carve their way through a dread-soaked ecology towards an inevitable battle with a cunning foe.

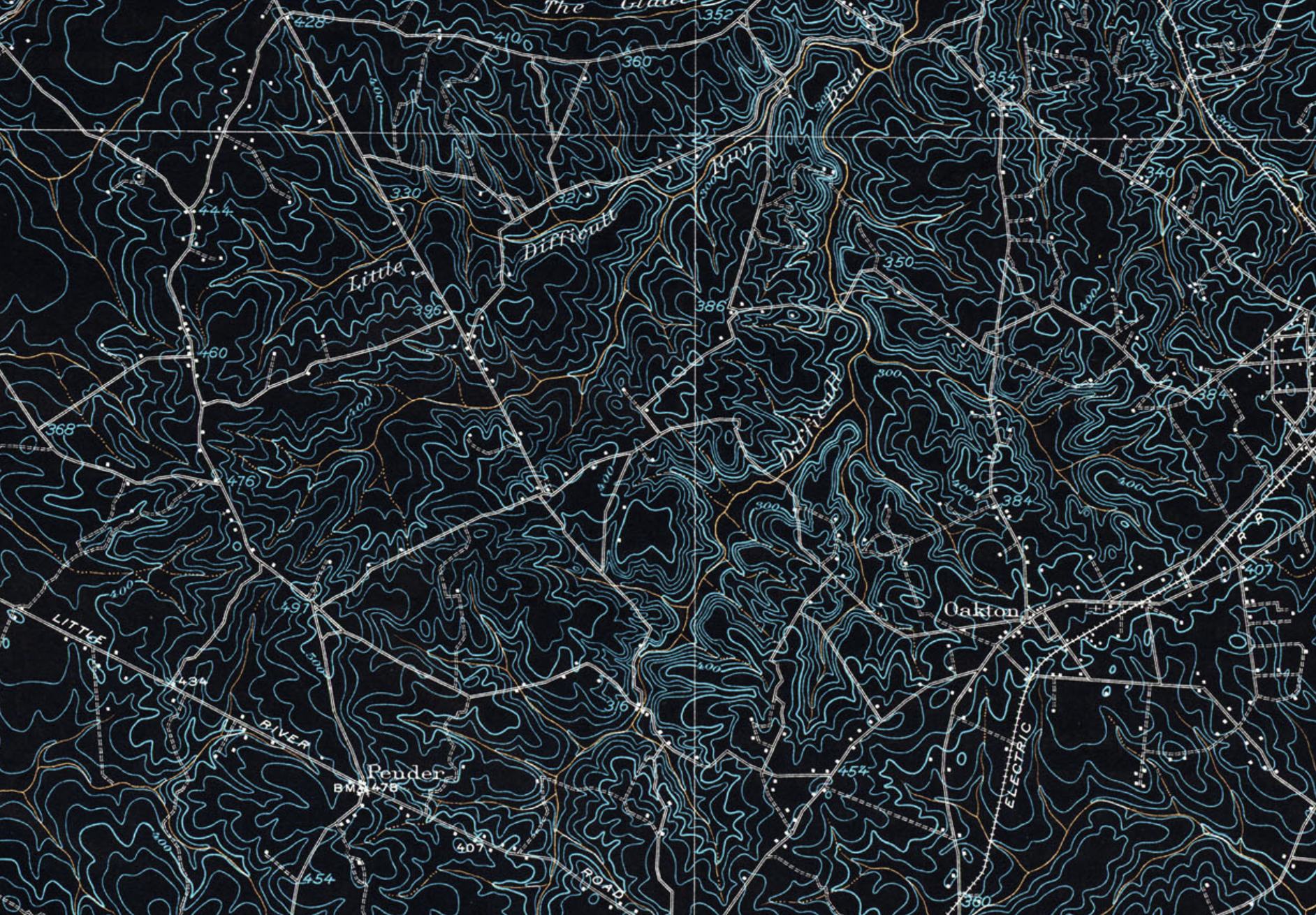

No mere fictionalization, “Scout Toward Aldie” was a high-fidelity recreation of the corridor between Vienna and Loudoun County to the west. The narrative arc of the poem itself conformed to the geography of Difficult Run, with the poet dropping breadcrumbs that identify familiar landmarks on the Federal cavalry’s trek westwards from Vienna.

“They file out into the forest deep,” marks a point of departure, by which the Yankee horsemen ride down the Lawyers or Old Courthouse Road towards an intersection with Hunter Mill. There, “they pass the picket by the pine and hollow log—a lonesome place.” Only to “cross the freshet-flood, and up the muddy bank,” moments later as they negotiate the historically troublesome ford of Difficult Run near Hawxhurst’s burned mill.

The fire-eaten structure and its attendant decay caught Melville’s eye. A few stanzas later, he remarks “a squirrel sprang from the rotting mill.” It wouldn’t have been far from the ford to Money’s Corner (today’s intersection of Lawyers, Fox Mill, and the Reston Parkway) where an 1862 Federal map had the road from Hunter’s Mill intersecting with the Fox Mill Road that led to Frying Pan.

Melville phrases this place in ways an after-action report never could: “By worn-out fields they cantered on—Drear fields amid the woodlands wide; by cross-roads of some olden time, In which grew groves, by gatestones down—Grassed ruins of secluded pride: A strange lone land, long past the prime, Fit land for Mosby or for crime.”

A stanza later, at an interval when the 2nd Massachusetts could have been passing the Frying Pan church, a favorite target and assembly point for John Mosby, Melville describes, “Hard by, a chapel. Flower-pot mould danced and decayed the shaded roof; the porch was punk; the clapboards spanned with ruffled lichens gray or green; red coral-moss was not aloof; and mid dry leaves green dead-man’s-hand, Groped toward that chapel in Mosby-land.”

Melville’s journey into the heart of John Mosby’s Confederacy continues over 801 lines. Of these, 56, or nearly seven percent—an auspicious number for a casual poem—make explicit mention of woods, trees, leaves, thickets, or branches.

It was, apparently, Melville’s seasoned judgement that one could not tell the story of the gray ghost without depicting the scenery that shielded the Confederate guerrilla from Federal raids. Melville probably said it best: “Maple and hemlock, beech and lime, are Mosby’s Confederates, share the crime.”

TWIN NARRATIVE

Symbiotic relationships between flora landscapes and John Mosby’s operations in Fairfax County represent a crucial linkage. Abundant hardwood timber and scrub brush or pine succeeding from previous land clearance efforts were the defining features of Difficult Run circa 1863. So too, these irregular groves were an important force multiplier for John Mosby and a motivator for locals who served with him.

This inextricable interrelation between people and forests long-preceded the outbreak of war. Understanding this long-standing co-evolution is an important pre-condition for grappling with Fairfax County during the 1860s.

In the opening sections of the definitive Fairfax County, Virginia: A History, Donald Sweig contextualizes early colonial Virginia with a borrow from Richard Hofstader, in which the eminent historian recalls a 1750 account from a mariner who claimed to have smelled the sprawling pine forests of the Old Dominion as far as one hundred and eighty miles out to sea.2

Beth Mitchell, devoted Fairfax historian and expert student of early metes and bounds, titled her exhaustive study of colonial Fairfax County property lines “Beginning At A White Oak” in honor of the “king of kings” tree that served as the most common and prominent boundary marker for surveyors.3

This arbor-oriented thought was not a later graft, but a contemporaneous feature of the way the land was perceived and communicated. When a proposal emerged in 1789 to move the County Court House westwards from Alexandria to a point near modern Annandale, locals bemoaned the prospect of shifting the municipal institution “into the woods.”4

The move was a loaded proposition. Equal parts opportunity and obstacle. In a pre-modern world, forests were both asset and hindrance.

An account from the late-17th century honed in on the labor-intensive raw forests of Virginia as a selling point to citizens of the Old World accustomed to the relative deforestation of their native land.

“So much timber have they that they build fences all around the land they cultivate. A man with fifty acres of ground, & others in proportion, will leave twenty-five wooded, & of the remaining twenty-five will cultivate half and keep the other as a pasture & paddock for his cattle. Four years later, he transfers his fences to this untilled half which meanwhile has had a period of rest and fertilization, & every year they put seeds in the ground they till. They sow wheat at the end of October and beginning of November, & corn at the end of April.”5

These forests and the nutrient-rich virgin soil they underlying them represented a tremendous prospect and a terrible burden. George Mason and other prominent landowners of Difficult Run property drew out prescriptive leases that stipulated tenants perform a variety of intensive upgrades to raw forest. The development and construction of fields, orchards, and tobacco barns all necessitated a huge outlay of calories and time.6

With this effort came an opportunity beyond crop yield. Old-growth hardwood harvested as a matter of necessity created a surplus of materials from which vernacular architecture and productive infrastructure sprouted. Forests quickly became houses, barns, distilleries, spring houses, outhouses, and miles of fencing.

Traces of these process still exist in Fairfax County.

Just south of the once-and-former Old Bad Road, otherwise known as Vale Road, the recently remodeled Squirrel Hill was first built with early-1700s hewn oak spline floors and rafters and a 1757 addition constructed primarily from chestnut.7

At Sully Plantation just south of Frying Pan, tulip poplar beaded siding harkens back to a history of abundant hardwood.8

Nearer still in both geography and chronology, George Waples III’s 20th century memoir, Country Boy Gone Soldiering, depicts the Upper Difficult Run valley being rich in chestnut trees. Waples specifies the iconic hardwood’s practical use as a farm instrument. “Those trees (chestnuts),” he wrote, “were also used for the rail fences throughout the south in the older times.”9

Locally-sourced, locally-processed, locally-utilized timber was likely the predominant pattern for early deforestation. In a region bountiful in old-growth timber, lands like Difficult Run that were poorly served by shoddy roads were unlikely to have fostered much interest for timber exporters. Instead, wood products probably stayed close to the areas from which they were harvested.

Adding complexity to the work-cost of these efforts was a lack of mechanical sawing capacity. The hand-sawn paradigm endured in Upper Difficult Run until the late-1780s when Amos Fox opened his titular mill.10

Fairfax historiography has a fixation with grain, which became the defining agricultural product of the 19th century. Historical narratives focus on the emergence of grifting capabilities at local mills while giving short shrift to the sawing operations that often co-occupied mill spaces with grist stones.11

Fox’s Mill was known to have been fitted with a sawing operation in the first decade of the 1800s, but the substance of an 1802 lawsuit from neighbor Thomas Fairfax against Amos Fox’s son Morris suggests that extensive timber sawing occurred along Difficult Run beginning in the late 1790s.

Fairfax took Fox to court for having illegally harvested a staggering amount of trees from the boundary between their two properties. The final tally was one thousand oaks, one thousand hickories, and one thousand other trees taken, amounting to a total of $6000 in damages.12

Beyond the obvious work load of felling and milling three thousand trees, it is amazing that Thomas Fairfax didn’t notice the loss of timber until the pilfering had reached an immense scale. The case speaks to both a culture of absentee landlordism in Fairfax and the laxity with which timber resources were managed and adjudicated.

In fact, trees—the defining natural feature of Western Fairfax County—were so common and undervalued as an asset that information about standing timber was a rare addendum to area real estate listings for the first three decades of the 19th century.

When Ann Fox died in 1813, a listing for her property at Fox’s Mills included information about slaves, livestock, and even distilling equipment, but not a word about trees.13 When eight hundred acres of nearby property was advertised for sale in March of 1821, a similar silence surrounded the question of available timber.14

Simply, it was not important.

TIMBER THRIVES IN PLAYED OUT LANDS

The apparent disinterest with which land brokers and investors treated timber in the early 19th century is an artifact of an interesting plateau in the relationship between humans of Fairfax County and their natural resources.

After almost a century of extractive cultivation practices, the area was on the cusp of a crisis. “Frontier communities are, by their very nature, notorious exhausters of the soil,” writes agricultural historian Avery Odell Craven. Describing the economic pressures that shaped early colonial farms in Virginia, Craven elaborates, “the one crop with highest value in outside exchange, drives all other major crops from the fields.”15

In Fairfax and tidewater Virginia at large, tobacco was the definitive cash crop that pushed all other agricultural considerations aside, for a time. The soil simply could not support the degree of production encouraged by eager frontier Virginians who saw vast wealth in the endless horizons of virgin land. By 1800, tobacco was nearly played out as a cash crop in Fairfax County. The quality of what comparatively little broad leaf was grown paled in comparison to the harvests of a few years prior.

With a quick stroke of ingenuity, Fairfax farmers replaced tobacco with wheat. Grain could be grown successfully on land too nutrient-sapped for tobacco.16 Alexandria quickly pivoted from tobacco hub to a leading wheat port. Those who segued into the new cash crop were handsomely rewarded as macroeconomic conditions in the Atlantic Basin created a strong international demand for Virginia grain. At its peak in 1811, Alexandria wheat merchants exported two million dollars worth of Virginia grain and flour.17

Many of the Civil War-era landmarks and much of the transportation infrastructure in Western Fairfax County were developed in the wheat years. Turnpikes were financed to bring Loudoun, Prince Willian, and Fauquier County granaries into alignment with Alexandria’s wharves. Innumerable mills represented enterprising attempts by savvy merchant middle men to intercept raw grain and process it for a premium.

The defining ecological feature of the early wheat years was a continuance of tobacco-era land use strategies. For wheat as with its noxious leafy predecessor, trees were both hindrance to the plow and competition for sunlight. As Fairfax County farmers rode the wheat wave, it behooved them to seek out well-cleared, well-lit, and largely flat parcels of land that demanded the least amount of effort to bring a profitable crop to market.

Hence, in 1813 flaunting available stands of timber in a real estate listing was not necessarily a wise strategy.

As before, the market for this cash crop settled at more modest demand (and price) levels. A historic culture of over-production encouraged further soil exhaustion. Expensive sub-industries developed around practices designed to elongate plantability and increase yields.18 Clover and Timothy cover crops, gypsum soil-amendments, and the application of expensive, but effective Peruvian guano helped Fairfax wheat farmers continue producing wheat, but at a heightened cost.

Large-scale gentlemen planters, like the owners of Sully Plantation, successfully kept their heads above water.19 Many others slipped into a cycle of asset liquidation and unceasing annual debt.20

Plenty of Fairfax farmers could not keep up with either the debt nor the onerous burden of planting increasingly unproductive land. From 1800 to 1840, the County’s population fell by thirty percent.21

The economic panic of 1837 and a subsequent money shortage in 1842 capped off this precipitous decline with a liquidity crisis that pushed many owners of used-up land past the brink.22 Land in Fairfax County depreciated rapidly. Five to fifteen dollars was fair asking price for an acre. For comparison, the rate for a similarly sized plot of land in New York at the same time was between forty and seventy dollars.23

As banking tumult and agricultural decline undercut the Fairfax farming community, timber suddenly began to factor heavily in real estate listings for land along Difficult Run.

Dogged by a lawsuit in the final year of his life, Fox Mill owner Gabriel Fox attempted to sell 203 acres of land along Difficult Run in January of 1843. Assurances that the property’s acreage was “a large proportion heavily timbered” figured prominently in the listing Gabriel took out in the Alexandria Gazette.24

Three months later, the owner agents for a two hundred acre property located between Fox’s Mill and the Little River Turnpike promised would-be buyers that the “greater part” of the farm was in “heavy timber.”25

“An ample quality of Wood and Timber” was the verbiage used to accompany the 1847 auction listing for a similarly sized plot of land west of Difficult Run near Frying Pan.26

The inducement was clear. Gabriel Fox’s 1843 land listing put it most astutely: “timber will always find a ready sale at the Court House.”

For a community pinched in a liquidity crisis, timber represented an incredibly salable asset. Once harvested, timber became chattel. Like slaves, cut hardwood timber was one of the best liquid assets one could own in a monetary crisis. Easily sold, appreciating constantly, and requiring no upkeep—stands of old growth timber were a savvy way to convert existing resources into quick value.27

As with tobacco and wheat before, microeconomies enveloped this fresh cash crop in tendrils of infrastructure that brought the resource to market. The 1850s found local investors and merchants reconfiguring to embrace and exploit this readily available timber into a network of demand.

An 1853 announcement from timber dealers along Accotink Creek in Fairfax Court House emphasizes both the abundance of white oak and red cedar timber and its suitability for the “ship timber and plank, wharf timber, millwrights, or wheelwrights.”28

Three years later, the Engineering Office for the then under-construction Alexandria, Loudoun, & Hampshire Railroad put out a public call for rail-road cross-ties “to be delivered in lots of about 2700 to each mile or section.” A hint at the available supply can be gleaned from the specificity of the request. The engineers sought only “perfectly sound White Oak, Post Oak, Chestnut Oak, Chestnut, or Locust timber, cut into lengths of 8 feet.”29 Modern carpenters will never know what it feels like to be this picky.

The coup d’grace in this glut of hardwood timber pouring out of the Difficult Run area came from a disgraced English wool wholesaler named Benjamin Thornton. He and his brother skedaddled from their native land in the 1840s under duress from a cloud of accusations including forgery, the cashing of substantial amounts in bad checks, and general fraud.

Thornton and his brother Joseph resurfaced in Fairfax County in 1852 with a new heap of investment capital and a vision for yet another crack at the merino wool industry. Having acquired 8,200 acres of prime forest land north of Lawyers Road in modern Reston, Benjamin Thornton apparently had a business epiphany. Sheep generally require pastureland and hardwood tree canopy generally precludes good grazing foliage. Benjamin Thornton identified an important opportunity as he cleared his land of oaks.30

An 1857 profile in the Alexandria Gazette marks the departure of the brig Wabash from Alexandria with “a cargo of 300 sons ships timber, shipped by Benjamin Thornton, esq. of Fairfax County, who has yet about 3000 tons for the same destination.”

Though Thornton was well-situated to exploit what the Alexandria Gazette called “the great scarcity (of timber) on the other side of the water,” he was not alone. The author concluded the piece by describing a network of Alexandria-aligned woodsmen who “for a year or two past…have been engaged in cutting timber and shipping it to the eastern markets, where it finds ready sale and pays a handsome profit.”31

Thornton initially used the Potomac canal to transport his timber to Alexandria. That changed in 1858 when the oak-rail hungry Alexandria, Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad began operations. Both Benjamin Thornton’s milling complex and Hunter’s Mill enjoyed stations that were no doubt planned into the rail route by virtue of the wealth of timber that was rolling out of Difficult Run by those points.32

A few short years before the outbreak of war, an authentic boom was taking place along Upper Difficult Run. All of the important preconditions had been satisfied. An existing and previously undervalued resource was identified. Domestic and international markets emerged. Infrastructure developed.

By the time a fresh national liquidity crisis emerged with the Panic of 1857, savvy landowners and eager speculators were already trading in a robust real estate market symbiosis premised on the value of timber leases.33

An 1856 advertisement for the sale of one hundred and ninety seven acres of land near Frying Pan began by addressing the target audience: “TO WOOD AND TIMBER GETTERS.” The prime selling point was a tract “very HEAVILY TIMBERED with oak and pine of large size.” Ad copy quickly doubled back to business-minded woodsman. “Wood and timber getters are particularly invited to view this property,” the broker opined, “as property so suitable to their purposes is seldom offered in market.”34

That same year, real estate investor MC Klein sold two tracts of adjoining land on Difficult Run just north of Fox’s Mills and south of Old Bad Road. A familiar pitch centered on the value of the trees that crowded the creek basin. The ad that Klein and business partner James Love ran in the Alexandria Gazette pointedly described the land as “bounded on the west by Difficult Run, on which there are Merchant Saw-MIlls of convenient access; also, abundantly supplied with timber of original growth.”35

This amounted to a turn-key business proposition. Buy the land that has the trees, fell the trees, and then drag them south along Difficult Run to Fox’s Mills or north to Hawxhurst’s Mill where you can convert the trees into supplies or specie.

Alexandria-based land speculators John and Wilmer Corse (younger brothers, incidentally, to Montgomery D. Corse—commander of the 17th Virginia Infantry and eventual skipper of George Pickett’s “lucky” fourth brigade that spent the Third of July, 1863 guarding the railroad at Hanover Junction rather than storming Cemetery Ridge), coined a phrase that appeared time and time again in late-1850’s advertisements for tracts of land in Western Fairfax County.

Quoth the brothers Corse: “There could be wood and timber enough sold off this place to pay more than the price asked for it.”36

More than a fad, the timber investment mentality had weight to it. By 1860, major lenders and investors like Tom Love, his son James Love, Lee Monroe, and Joshua Coffer Gunnell, had purchased large tracts of land on or abutting the upper Difficult Run Basin.37

FORESTS AT WAR

To say that the Upper Difficult Run has been overlooked in Civil War historiography would be an understatement. With a few choice exceptions, it has been neglected entirely. The National Park Service knows with a degree of certainty where the wood lines were at Gettysburg, but a similarly rigorous understanding of the landscape jacketing the creek beds and undulating hills north of the Little River Turnpike has likely been lost to history.

We’re left to reconstruct the wartime ecology from a hodge podge of sources ranging from tax records and real estate announcements to post-war accounts of land use and aerial surveys conducted seventy years ex post facto. What emerges is a landscape marbled with cultivated farmland and dense timber. Neither fully virgin forest nor rolling wheat fields, Difficult Run was a patchwork culmination of a century or more of extraction and processing practices writ large on the land.

The 1870 agricultural census attests to mixed ratios of woodland and improved land. Along the Little River Turnpike and west of Fox’s Mill, one substantial tract enjoyed thirty cleared acres set amongst three hundred acres of trees. Across from today’s Waples Mill Elementary School, two hundred improved acres encircled sixty two timber acres. The area around Fox’s Mill was just about a fifty-fifty split. The modern intersection of Vale and Fox Mill Roads was similarly disposed. North of Fox’s Mill in the Difficult Run valley across from the property that MC Klein listed in 1856, John Fox paid taxes on two hundred and seventy five wooded acres in 1870.38

Other such documents corroborate the abundance of timber on Difficult Run in the years after the war.

A July 1867 real estate transaction between Thomas Lee and the new owner of Fox’s Mill, Henry Waple, yielded a prolonged legal dispute centered around disputed acreage that was “being in timber.” It’s clear that there was a belt of timber at least twelve acres large east of Difficult Run and spread between the road to Fox’s Mill and Fox’s Lower Mill to the north.39

Just across Difficult Run, James Fox’s farm went to auction in 1877. The land was described as “well wooded.”40 Identical verbiage was used as enticement in the auction announcement for an 87 1/2 acre farm “near Fox’s old mill” the following year.41

In 1881, the 617 acre Whited Tract south of Lawyers Road and west of Hunter’s Mill Road went to market as a “valuable tract of TIMBER LAND.”42

Not only was the market for timber intact in the decades after the war, but the supply was still available. Timber of the quality advertised here could not have sprouted magically in the interregnum between Appomattox and 1881. These valuable trees were surely in place and fully grown during the war years.

Stands of old-growth investment trees were only part of the equation. Extensive early colonization and especially tobacco cultivation on the sandy-soiled floodplains of Difficult Run likely established a succession regime of impenetrable undergrowth. Much of the Lawyers Road line—an early colonial corridor for both transit and homesteading—was known to be densely thicketed during the war.43

Students of the Civil War in the east might recognize this description of thick undergrowth thriving where primary growth trees had been clear cut previously. The Wilderness in Spotsylvania County similarly beguiled fighting men of both armies who were pushed to the tactical brink by vision-obscuring brambles and bushes.44

Interestingly, the Wilderness was the product of patterned deforestation beginning in the late 1830s and accelerating into the 1840s with the establishment of a smelting operation at the Catherine Furnace. Trees were felled and burned to feed the pig iron fires at the facility on a scale and timeline that matches the emergence of timber production in the Difficult Run Basin.

The comparison is worth pondering. As Melville plainly describes, dense foliage unsuitable for fighting sounds consistent with a mini-Wilderness within Difficult Run.

ENTER MOSBY

John Mosby found his way through the forest of Difficult Run during the first winter of the war. On February 12, 1862, then Private John Mosby was on picket duty in Fairfax Court House when JEB Stuart ordered Captain William Blackford to detail Mosby on a curious mission. The future partisan was tasked with accompanying “two young ladies living at Fairfax Court House, acquaintances of his (Stuart) had arranged to send them to the house of a friend near Fryingpan.”45 These women were likely the cousins Antonia Ford and Laura Ratcliffe who became frequent companions and admirers of Stuart.

On that February night, Mosby likely ferried the women along today’s Waples Mill and West Ox Roads. A prominent local roadway at the time of the war, it was also the most direct avenue between the two points. This route would have taken the party within a stone’s throw of Fox’s Mill and throw the hardwood forests that crowded the banks of Difficult Run at Fox’s Ford.

Mosby would be back, and soon. In the last days of August 1862 as Confederate and Federal forces brawled on the plains of Manassas southwest of Difficult Run, Mosby was fulfilling his duties as one of JEB Stuart’s most renowned scouts. Nervous Yankee farmers who were living in Fairfax County despite the ebb and flow of hostile forces sensed a new hazard. On August 28, Alexander Haight of Sully Plantation decided to flee to the safety of Union lines.

John Mosby and a squad of Confederate cavalry interrupted Haight’s flight from Fairfax at the corner of the Chain Bridge and Hunter Mill Roads in modern day Oakton. At the iconic oak from which the town derived its name, Mosby asked Haight for his papers. Haight handed over the documents and spurred his horse on a mad dash for freedom. He escaped safely despite having to dodge seven pistol shots.

Mosby returned again four months later as the vanguard of a JEB Stuart raid that targeted Federal stores at Fairfax Station before escaping via the Hunter Mill Road/Frying Pan axis. As the Confederate force rode through Vienna, they captured “a large number of ‘contrabands’ engaged in felling timber in the neighborhood of Vienna.”46

A few hours after intercepting an illicit deforesting operation conducted by freed slaves, Stuart signaled to Mosby his intention to establish the young scout as an independent partisan ranger.47

It is little wonder that Mosby returned to the forested roads he had scouted over the prior two years. The belt of trees between Frying Pan and Vienna satisfied both conditions essential for John Mosby’s success. These forests were laced with little used paths—some ancient, others more recent, such as the timber skids that surely connected property’s like MC Klein’s to the adjoining commercial saw mills. So too, these little used paths connected plots of land that were home to families that were sympathetic or supportive of the Confederate cause.

The sons of these families swelled the ranks of Mosby’s Rangers and augmented the command with an encyclopedic knowledge of paths connecting mills to markets, highways to shunpikes. By no coincidence, an overwhelming number of Rangers from Difficult Run were connected to the timber industry.

The forest ecology was also an economy and that economic/ecologic guild was the lifeblood of Confederate families in the basin.

As sons of the family that owned a significant sawmill, Ranger Lieutenant Frank Fox and his younger brother, Private Charles Albert Fox, benefited from an obvious connection to healthy timber resources. Their brother-in-law, Jack Barnes, not only married into a milling family, but had inherited his own mill on Pope’s Head Creek. Their neighbor, Jim Gunnell, became a professional charcoal producer after the war.48

Just up the road, neighbor and early ranger enlistee Minor Thompson was a carpenter by trade. Still other neighbors, the Trammell family, benefited from the Hunter Mill timber economy. Deepening their ties to that economic sphere was the marriage of Margaret Trammell to woodsman John Underwood.

It was said of Underwood that he knew paths even rabbits hadn’t found.49 Described as a native of the Frying Pan area, Underwood likely worked the timber belt near the Thornton holdings north of Lawyers Road. As a favorite scout for John Mosby in 1863, Underwood converted his former workplace into a maneuver corridor and ambush venue.50

MOTIVATION BY THE CORD

In retrospect, secessionist thought feels like an automatic product of Southern identity. We allow ourselves to assume these sentiments were the prime motivators for Confederate service. It’s important to consider that the economic and ecologic context of their lives inspired a deeper practicality.

For men who were tied to the forests of the Upper Difficult Run Basin, independence meant safeguarding one’s family and one’s livelihood. Regular Confederate service could satisfy some abstract sense of protecting the South from the Yankees, but the reality of Civil War armies and the nature of logistics in the conflict could potentially have inspired men connected with the local timber industry to pursue a special pragmatism.

Civil War armies consumed resources at prodigious levels. More than food or gunpowder, brigades of men ate trees and wood. One estimate puts the rate of wood consumption at 400,000 acres of trees used per year of the war amounting to two million acres of trees used by the end of the conflict.51

Fairfax County, Virginia saw the worst of this process. The post-war landscape resembled a “prairie” devoid of trees and structures.52 An account of wartime Fairfax Court House printed in the New York Times painted a similarly bleak portrait of the landscape: “Farms and orchards have been made into common roads, fruit trees are uprooted, forest burned, fences destroyed, and the whole country presents a melancholy air.”53

Local records from the post-war Southern Claims Commission further attest to the scale of timber and timber products consume during the war. William Ansley of Flint Hill had an entire home consumed for firewood as well as 5000 yards of fencing. Josiah Bowman, who lived on a hill overlooking the Union cavalry camp at Vienna, claimed 2000 shingles, 38,334 rail stakes, 10,000 rail posts and 3,254 cords of wood. Flint Hill’s Squire Millard lost a paltry two cords of timber, 1467 rails and 2705 cords of wood on top of the loss of a 30’x40’ wood barn and a dwelling house that were consumed for fire wood.54 All taken by the Army of the Potomac.

No matter the affiliation, an army occupation had the potential to eat away a literal fortune worth of resources. A passing two week interlude of camp life near Difficult Run could erode the prospects of secessionist farmers and woodsmen for a generation to come. If the South won the war, but locals lost all of their timber, would they still be victorious?

By December 1, 1863, the Confederate army had occupied the area around Difficult Run twice and the Army of the Potomac had been through three times. Worse yet, the “contraband” free slaves that JEB Stuart and his men captured near Vienna in late December of 1863 were symptomatic of a larger deforestation effort. On August 18, 1864, Lt. Col. Benjamin Alexander, Chief of Engineers for the Military District South of the Potomac, provided an insight to the sourcing efforts that provided timber assets to the prodigious fort-building efforts around Washington, D.C.

Alexander wrote, “We are again in want of a considerable quantity of timber and abates for the works South of the Potomac. That obtained from vicinity of Vienna last spring will be exhausted by the structures in progress at Fort Wards and Fort Ellsworth.”55 In this case, “last spring” would indicate a time frame of Federal timbering in Vienna at some point early in 1863—precisely the time that John Mosby arrived and local men joined his efforts. This immediate pressure to valuable timber reserves cannot be understated in the motivational matrix for local Confederate rangers.

It behooved locals to assert control over the landscape by turning the basin into a no-go zone for marauding Yankees and an area whose challenging landscape and absence of enemy threats would not encourage the presence of a mainline Confederate unit. Whether intentional or not, zealous partisan warfare was possibly the smartest strategy for ensuring valuable timber remained at war’s end.

As the 1870 agricultural census and post-war real estate listings attest, the abundant timber along Old Bad Road survived the war. Fairfax County rebuilt in the ensuing decades. The many burned fence posts, railings, and structures were replaced with freshly hewn timber that was processed at places like Waples Mill, as Fox’s Mill came to be known after it was reopened in 1867.

The fact that a commercial saw mill was able to sustain business within two years of Appomattox hints at the degree of timbering occurring in the basin. Fifteen years later, the Vale area (where modern Vale and Fox Mill Roads intersect) was known as a hub for charcoal production.56 Charcoaling was typically a follow-up industry that rode the coattails of broad-scale timber harvesting to convert unsatisfactory wood products into a viable fuel product.

With an abundant supply of timber and eager local markets for both wood products and charcoal, the extensive scale of deforestation along the route once known as Old Bad Road is easy to express. In 1964, County Planner Rosser Payne connected the success of previous charcoaling endeavors to the lack of large trees in the land north of Vale Road.57

Timber sustained Difficult Run after the war as it had before. This economic incentive presents important context to the area’s role in the Civil War. Mosby’s war in Fairfax County and the fervor with which he occupied and manipulated the land along Difficult Run created a symbiotic strategy. Mosby could terrorize and maraud against Federal forces while local men could preserve an asset by fostering an enduring notion that the basin was a place best left alone.

Though woodland assets enriched the community in the wake of the conflict, this success was purchased at cost. Frank Fox and John Underwood—men whose economic identities were premised on preserving productive woodland—did not live to benefit from the arrangement. Minor Thompson’s younger brother William did not survive to partake in his brother’s post-Appomattox successes. Still others were tarnished by diseases contracted in service or the physical toll of prolonged time spent in Federal POW camps.

Human cost aside, it’s essential to consider the potent confluence of ecology and microeconomics that preceded, potentially motivated, and likely sustained guerrilla warfare on Difficult Run.

A CENTURY LATER

In a curious twist of synchronicity, the same area where a blend of forest and motivated locals played host to a successful guerrilla campaign provided a venue for an important chapter in 20th century counter insurgency.

One hundred years after John Mosby infiltrated Difficult Run, a state department employee named Robert Hilsman rode out to Hickory Hill—a tony house off Chain Bridge Road north of Vienna. Fresh from Vietnam, Hilsman pitched then Attorney General RFK on a group of strategies designed to eradicate communist Vietnamese guerrillas who fought not unlike Mosby had a century before.58

Prominent in this package was a program named Strategic Hamlets in which rural civilian Vietnamese were to be removed from the countryside and concentrated in more developed areas that could not hide guerrilla fighters. The less well-publicized corollary to this project was still another initiative, this one more sinister.

Instituted the same year as Strategic Hamlets, Operation Ranch Hand pursued the systematic deforestation of the Vietnamese landscape by chemical amendment. Incredibly toxic, this broad scale ecocide has reverberated in the genetics of all the Vietnamese and Americans who—unwittingly or not—participated in it.59

On the ridge overlooking Difficult Run, a latter-day Phil Sheridan in bureaucratic garb was attempting to process lessons learned during the Civil War. The only imaginable way to win against the VC was to parse the insurgents from the population and peel away the ecology that sheltered them both.

The key to victory in Vietnam was well known to Herman Melville and the Federal troopers with whom he rode through Difficult Run in 1864: there would be no war without the trees.