TL;DR–During the Civil War, a unique configuration of landform, vegetation, bad roads, micro-polities, and valuable timber created a pocket of chaotic violence near today’s Dulles Corridor

On March 7, 1865, twenty-two Yankees from the 16th New York Cavalry left their camp at Vienna on a routine patrol to Fairfax Court House five miles to the south. Not far from Flint Hill (modern Oakton) thirty rebel guerrillas emerged from the woods to the west and mauled the Union cavalrymen. Two New Yorkers were killed and three more captured. The Rebels suffered no losses.[1]

It was a small, but astonishing event. The Confederacy was, after all, weeks away from its demise. More importantly, this lopsided ambush took place less than fifteen miles west of the White House in nearby Washington, D.C.

Unannounced ambushes plagued Federal troops left to guard the capitol’s western periphery. Brief and gory episodes were de rigeur in Fairfax County, where no degree of due diligence nor surge of manpower could stymie Confederate guerrillas.

Mosby was to blame. The hyper-effective partisan leader whose notoriety was hard won in cunning pistol fights on this same line inspired a perception not unlike that bestowed upon the Vietcong. Though Mosby himself was not always present and the men who marauded through Fairfax County were not always under his command, “Mosby” became like “Charlie”: a catch-all for the pervasive fear inspired by effective guerrillas who congealed from and melted away into the forests.

The number fifty thousand has been bandied about to quantify the amount of Federal troops that Mosby’s efforts in Northern Virginia necessitated in order to ensure Washington, D.C.’s safety. On a sixty mile arc from Front Royal to Bailey’s Crossroads, Yankees that could otherwise have bolstered the Army of the Potomac were held close at hand to address potent guerrilla raids.

How is it that Confederate guerrillas were able to effectively sever a Union main supply route deep in Fairfax County a month before Lee’s surrender one hundred and thirty three miles to the southwest?

In their regimental history of Mosby’s Battalion, Hugh Keen and Horace Mewborn attach a simple methodology to the prolific guerrilla chieftan. “The command,” they write, “used back roads and little known paths.”[2] Simply, superior place knowledge and the flexibility to work with landform empowered Confederate guerrillas in Northern Virginia.

Some background worth pondering:

- The area just west of Flint Hill and Vienna above the Little River Turnpike as far west as Frying Pan was heavily timbered. These trees were both medium and motivation for local Confederates.

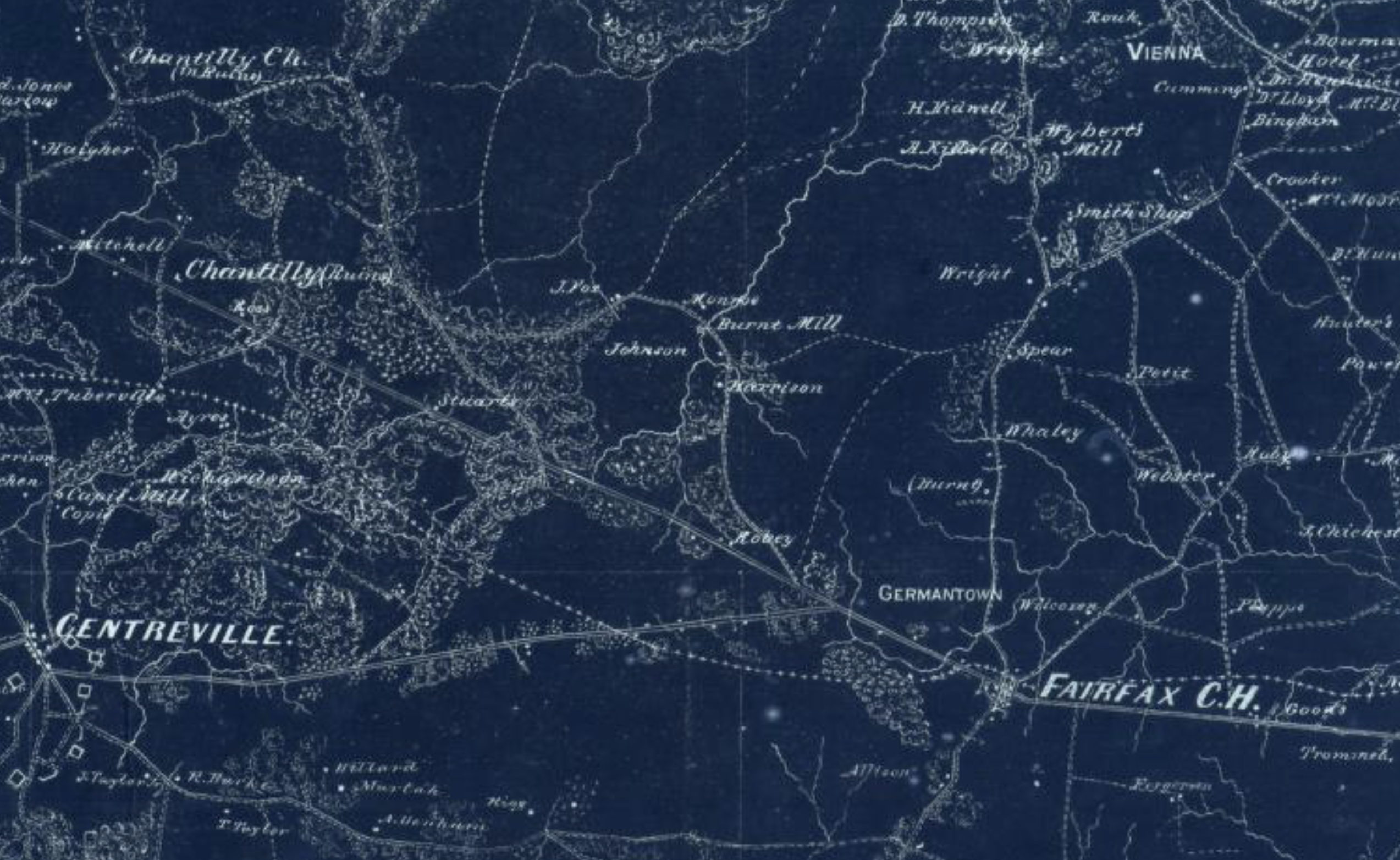

- Physical maps of the area were notoriously inaccurate. Confederate maps reflected more nuanced and accurate information. Yankee maps encouraged avoidance.

- Difficult Run and its tributaries defined this belt of woods. Mills sited on its lowest points were hubs in informal path networks. Some trails up draws and along the creeks could potentially date to prehistory. Guerrillas likely used these creek beds and nearby paths as roads.

- Confederate allegiance was strong in this valley. Many families located along Difficult Run sent their sons and husbands to Mosby’s Battalion. More participated in the larger Confederate war effort. Confederate forces utilized a forward base of thickets, farms, and mill marshes just west of Fairfax Court House. Hidden by hills, rife with muddy shunpikes, jacketed in trees, this area was a warren of military interior lines connecting vital routes for infiltration and exfiltration.

- This pattern continues in a broad fan to the west. Mosby men and their families controlled and understood the many hydrology basins that defined the interface where the Difficult Run watershed collides with the rolling plains of the Culpeper Basin.

These opportunities enabled Mosby and his men to occupy friendly ground that brought them within a stone’s throw of the Yankee camps at Centreville, Fairfax Court House, and Jermantown.

The most lethal edge of this guerrilla geography was its eastern limit along Hunter Mill Road where a nest of Mosby families hosted a killing spree in the woods adjacent to the Union camp at Vienna.

ADVERSITY & OPPORTUNITY

John Mosby inherited an ideal laboratory for asymmetric warfare. His arrival in early 1863 slotted behind two years of intermittent violence on the line of the Chain Bridge Road between Fairfax Court House and Vienna and the Hunter Mill Road which jutted out from the Chain Bridge Road at Flint Hill.

A rugged, undeveloped atmosphere predominated. The roads were poor and remained poor after the war. The Chain Bridge Road between Fairfax and Vienna retained its unruly, mud-drenched quality well into the 20th century. In 1915, weary locals belonging to the Fairfax County Improvement League mounted a campaign to have that stretch of history road marked with signs that read “Fairfax Folly.”[3]

One Federal map sketched after “A Rapid Reconnaissance” in October of 1861 described the Chain Bridge Road north of Fairfax as “hilly, uneven, sunk at places from 6 to 8 feet below the adjoining ground and badly drained.”

The mud alone was not the only issue. As a Federal cavalry commander who survived an ambush in the thickets near Difficult Run in 1861 phrased it, panic set in amongst his command as Confederates fired into their ranks while riding on a “very narrow” road “hemmed in on both sides with trees.”[4]

The abundant foliage bounded up the poor roads to create kill zones where marching columns would bunch up and lose both their ability to maneuver and their visibility. So ripe were the conditions for guerrilla warfare that conventionally trained soldiers reverted to bushwhack tactics near Hunter’s Mill as early as 1861. West Point graduate and old army cavalry veteran Robert Ransom, Jr. orchestrated the very same forest ambush previously described as a panic.

In an after action report eerily prescient of John Mosby’s later accounts of guerrilla warfare along Difficult Run, Ransom described guiding one hundred and sixty picked men of the First North Carolina Cavalry “by a small path through thick pines and oak woods.”

Ransom and his men assembled a half mile away from Hawxhurst’s Mill and then stalked the woods around Hunter’s Mill where they established another pattern that would become a cornerstone of Mosby’s operations.

One of many staunchly Confederate locals, Edward Johnson, relayed valuable information about a company of Federal cavalry that had passed not long before. Ransom followed and attacked this unit from the rear as is funneled through a deep cut in Lawyers Road.[5]

The Federals were routed that day and a key characteristic of Confederate cavalry tactics west of Vienna was set in stone. Friendly locals and thick vegetation incentivized Rebel horsemen to break up their columns and thread across the landscape, choosing either to pass through unseen or spring an ugly ambush on unsuspecting Federals.

Rebel forces continued to prey upon their Yankee counterparts through the Winter of 1861-1862. In February, the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry had enough. A patrol rode into Flint Hill and torched a barn where Confederate pickets were known to roost. Then they proceeded to the Peck House located on Hunter Mill Road where today’s Hunter Valley road intersects above Vale. A firefight ensued with muzzle flashes emanating from the house itself as well as “the neighboring hills and woods.”[6]

Another predictable outcome occurred in September of 1862. A Federal cavalry patrol probing northwards towards Vienna came to grief in the woods near Flint Hill. Colonel Beardsley of the Ninth New York described the action, “we got into a thick wood at the cross-roads this side of Vienna, when they gave us a volley and retired, killing several and wounding about 20.”[7]

Fitz John Porter astutely diagnosed the situation at Vienna on September 2, 1862 when he reported that “the country beyond our picket lines affords every facility for such surprises.” Much maligned Fitz John Porter had some further sage words for Federal authorities. “The commanding general must expect them (attacks) to be frequent so long as the enemy continues in large force in our front and wishes to divert attention from other movements.”[8]

Over the next two years, this reality transformed Vienna, Virginia into an armed camp. Writing in February of 1864, Herman Melville described the place in language couched on twin pillars of ecological clear cutting and dread.

“The cavalry-camp lies on the slope

Of what was late a vernal hill,

But now like a pavement bare—

An outpost in the perilous wilds

Which ever are lone and still;

But Mosby’s men are there—

Of Mosby best beware.”

STRATEGIC REALITIES

The Federal disposition at Vienna was problematic for the entirety of the war. From 1861 until March of 1865, Yankee cavalry was subject to period ambushes at points all along their line. Guerrilla units routinely penetrated their pickets, and infiltrated deep into the rear where they destabilized a Union force ten times their size.

Very early in the war, this paradigm produced a practical calculus. When Confederates withdrew from Fairfax Court House in March of 1862, Federal presence became a permanent, if tenuous, fixture of western Fairfax County. The position at Vienna was a crucial piece of the local tactical schema.

The Difficult Run Basin from which Mosby frequently emerged to wreak havoc was centrally located between important north/south ridge roads. Three hugely important east/west highways—the Warrenton, Little River, and Leesburg Turnpikes—cut through the watershed. The camp at Vienna sat astride the most important of these ridge roads, the Chain Bridge Road, and covered its intersection with the equally important Leesburg Turnpike at Tyson’s Corner.

If Federal cavalry quit Vienna, they would sacrifice their advanced pickets on the Hunter Mill line and would inhibit their ability to patrol and project on a wide arc from Herndon to Frying Pan and Chantilly. Diminished Yankee presence along the Chain Bridge Road would invite increased Mosby marauding into Maryland that would jeopardize the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which was an important lifeline to Federal armies moving up the Shenandoah Valley.

Worse still, Vienna was the only position covering the broad Accotink watershed, which was already a favorite Mosby haunt despite the fact that it was miles behind nominal Yankee lines. If Mosby established himself in Accotink, Fairfax Court House would be in jeopardy and, more important, so would the vital Orange & Alexandria Rail link, which supplied Federal campaigns in Central Virginia.

Simply, Vienna had to hold to maintain both local tactical and theatre-wide strategic initiative.

The chief obstacle in maintaining this position was ecological. Abundant foliage made observation and pursuit a difficult proposition for Union forces. So too, the wealth of trees that made the Vienna line so lethal were a critical aspect of the Union war effort.

By 1862, Vienna was the terminus of the once proud Alexandria, Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad. The tracks west from there had been destroyed so that trains coming from the capitol could go no farther than Vienna.

Deeper context sprouts from antebellum history when the stretch of track immediately west of Vienna on the AL&H railroad was developed to serve a growing lumbering hub nearby. Huge stands of old growth hardwood on either side of the tracks became fodder for an emerging trade in timber exports to England.[9] On the eve of the war, the two rail stations west of Vienna—Hunter’s Mill and Thornton’s Station—were integrated into the railroad chiefly to handle bulk timber coming out of the valley.

The presence of this important timber belt and the infrastructure that facilitated its extraction did not escape the attention of Federal authorities. As early as 1862, Vienna was serving as a transportation hub for Yankee axe-men who were felling trees in Difficult Run to feed the war effort in Washington, D.C. and at large.

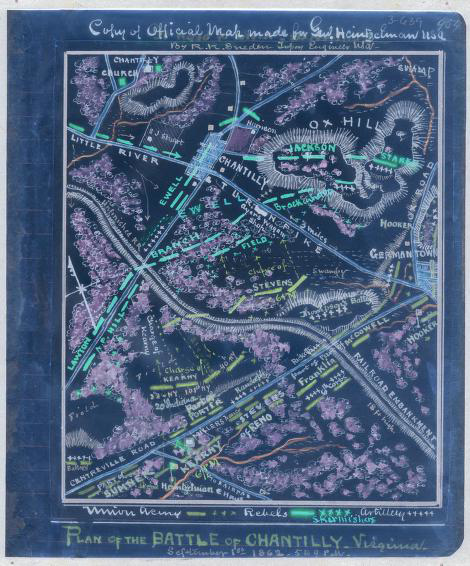

After the Yankee retreat from Second Manassas and the panic-inducing thrust of Stonewall Jackson towards Jermantown that culminated in the Battle of Ox Hill on September 1, 1862, General John Pope did a head count of Federal forces in Fairfax County to make sure everyone had tucked in behind the line of forts protecting Washington. The last unit to enter Federal lines was “the tree corps on the Vienna and Chain Bridge Road.”[10]

A May 1863 report detailing Union force dispositions in Northern Virginia describes one key function of General Abercrombie’s “moving division” of 8,600 men as “guarding the quartermaster’s woodcutters near Vienna.”[11] This pattern continued throughout the war. Just after Appomattox, a post-mortem material survey of Federal assets near Washington included a section on the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad. “The road is in complete running order to Vienna Station,” the reporting officer wrote, and “a large number of wood trains were run to transport the wood cut by Quartermaster’s Department.”

The scale of the harvest was immense. One report from Vienna dated June 20, 1863, indicates that 13,000 cords of wood were cut, stacked, and ready for transport at Vienna.[12] Assuming the timbered trees in question had a diameter at breast height of 22 inches, this figure indicates that at least 13,000 trees had already been hauled from the Vienna forests by mid-1863.[13]

Not only were the trees important aspects of the ecology, they were also economic assets. Timber was considered chattel, a very liquid instrument that could be readily brought to market. As an 1843 real estate advertisement phrased it in the pages of the Alexandria Gazette, “timber will always find a ready sale at the Court House.”[14] The loss of these trees was more than a passing concern for locals. Post-war prosperity was premised on retaining this wealth.

Equally important was the composition of the tree corps doing the actual logging.

In late December of 1863, Confederate cavalry chief JEB Stuart led a raid into Fairfax County. After looting the railhub at Fairfax Station, Stuart led his men (including his finest scout, John Mosby) north through Fairfax Court House to Vienna where they cut across Hunter’s Mill to bivouac at Frying Pan. As the Gazette put it, these Confederates captured “a large number of ‘contrabands’ engaged in felling timber in the neighborhood of Vienna.”[15]

It was the confluence of anxieties. Secession motivators in Fairfax County tapped into deep-seated fears by which economic subjugation of white southerners went hand in hand with the elevation of African-Americans. In late 1862, contrabands—freed slaves—were actively separating locals from their assets while armed Federals guarded them. This could be interpreted as proof positive of the worst fears harbored by Secessionists.

Not coincidentally, the discovery and capture of freed slaves felling hardwood near Vienna preceded the creation of John Mosby’s independent command by only a few hours. Regimental historians Hugh Keen and Horace Mewborn point to the account of John Scott who described the scene at the Ratcliffe House a few miles west of Vienna later that evening.

“Stuart…announced that he intended to comply with Mosby’s request to leave a few men behind to protect the loyal Southerners of northern Virginia,” wrote Scott.[16]

Over the next two months, the Hunter Mill/Vienna corridor went from contested no man’s land to an axis and venue for hyper effective Rebel guerrilla warfare. So successful were Mosby’s early raids on Frying Pan and the Ox Road that Federal cavalry commanders petitioned to withdraw the main picket line east of Difficult Run, to a position out front of the Chain Bridge Road at Flint Hill, Hunter’s Mill, and Vienna.[17]

By early June of 1863, quick scouts and sharp sniping in the woods west of Vienna transitioned into full scale fire fights. One of Mosby’s most trusted and knowledgeable scouts—a woodsman who had married into the Trammell family that had been a fixture of Hunter’s Mill for generations—orchestrated a designed ambush of the 5th and 6th Michigan on Lawyers Road.

Once drawn into a chase, the Federals unwittingly entered the box. Mosby and his main element of seventy-five men crashed through the Federal column with pistols blazing. Though encircled and outnumbered, Mosby escaped with only modest casualties.[18]

Bob O’Neill, author of Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby and Small But Important Riots, pulled the correspondence of Lieutenant Colonel Allyn Litchfield of the 7th Michigan, who described the Mosby ambush in a letter to his wife on the following day. Not content to spell out the various Yankee forces that were patrolling on the Ox Road (today’s Waples Mill Road) and Lawyers Road, Litchfield drew a map, which O’Neill copied and has graciously allowed me to use here.

When overlaid with an 1864-vintage Confederate map, the dotted path of the rebels and the X-marked ambush site on the Lawyers Road corroborate Confederate presence along Difficult Run and violence near Hawxhurst’s and Hunter’s Mill.[19]

Further evidence of privileged Confederate place knowledge and a sense of impunity with which Mosby men regarded their affairs in the woods west of Vienna came in the late-20th century when Mosby scholar Tom Evans and his son found the famed Hidden Valley camp.

The story of the site’s rediscovery is best told in Don Hakenson and Chuck Mauro’s A Tour Guide and History of Col. John S. Mosby’s Combat Operations. The father/son duo uncovered a makeshift anvil made from wrecked train rail and a number of discarded horseshoes, which corroborated oral legend that Mosby maintained a reshoeing station along Difficult Run where recently captured Yankee horses could be shod before being led back into Confederate lines.[20]

This secluded micro-valley was the venue for a notorious pre-war grog shop, which served African-American clientele. In 1860, Fairfax County brought charges against its owner, Charles Adams, a local brigand who happened to be first cousin once removed to two Mosby Rangers, Ira and John Follin.[21]

A quarter mile northeast of this hidey-hole, Adams’ property (which abutted that of his wife) bordered Difficult Run, across which could be found extensive property owned by three Gunnell siblings. One of whom, Martha Gunnell, was married to Richard Dorsey Warfield, Sergeant of Mosby’s Company B. On the night of October 18, 1864, a deep raid into Falls Church culminated at the border of these properties when a Mosby Ranger brought civilian school teacher John D. Read to his knees on the ruined railroad bed and executed him.[22]

The killing was audacious. Not just because the victim was a civilian or that powder burns to his forehead left no doubt as to the scenario of his demise, but because the murder occurred less than two miles from the cavalry camp at Vienna. More embarrassing still was the fact that Read had been snatched from his brother’s farm three miles east of that same cavalry camp. Rebel partisans had threaded their way past Yankee patrols to a place that was mere minutes away from multiple Union regiments. The butternut rangers fired two shots and disappeared into the night.

As with the presence of the hidden valley reshoeing camp, this murder could only take place in a location where Mosby men felt safe. These moments and their geographic particulars represent the culmination of a deliberate tactical methodology. Mosby men dominated the area west of Vienna because they were from that area, had family in the area. Like locals anywhere, they had a unique understanding of nearby places and shortcuts between them. Their entire pre-war lives—the chores, errands, church trips, family visits that comprised their existences—were now military intelligence.

The cumulative weight of these experiences would have been a potent asset, especially considering that the Union cavalry base was literally surrounded and at intervals directly bordered by properties of Mosby men and their families.

John Underwood married into the Trammell family that owned land on either side of Hunter Mill Road, weaving scout Bush Underwood with Rangers George West Gunnell and LB Trammell. John F Saunders and Thomas Clarke were boyhood friends who grew up and fought with Mosby together in the same woods. William E. Moore, a particularly effective scout that Federals identified as being essential to Mosby’s operations near Vienna, descended from Baptist preacher Jeremiah Moore, whose bloodline (and, hence, Moore’s cousins) spread out throughout the creek valley and up into Flint Hill. LB Hunt and Richard Dorsey Warfield lived a stone’s throw away.

East of the cavalry camp, John and Ira Follin grew up on a property abutting the future Yankee camp. Their grandmother owned 338 acres of prime land immediately adjacent to a 422 acre spread owned by Hampton Williams, father of Company B’s Lieutenant Frank Williams. Just to the west of them, the Ferris family that ranger Minor Thompson married into just before the war owned 58 acres that almost touched the 109 acre plot of William Moore’s mother, Mary.

The Hunters of Hunter Mill fame were also cousins to William E. Moore. Their sprawling properties along Difficult Run and near today’s Route 66 in eastern Vienna would have been known to Moore and their other cousins, Rangers Gus and Richard Farr Broadwater.

AJI

Capture, encirclement, maneuverability, life and death are concepts central to the game of Go. Unlike chess, Go is played on vertices where lines intersect. Individual pieces are less important than the local and broadscale “shape” achieved by positioning many pieces together in certain configurations.

Two Go terms are helpful for understanding Vienna. Moyo, or framework, hints at an individual game’s development, in which islands of occupation grow and shift as the game grows older. The initial framework is created as first pieces carve out corners and relationships with other pieces. In these groups and the pockets that develop between and around them, aji, or potential, emerges.

Depending on the player and the moyo they have built, aji can either be good or bad.

It’s not enough to say that Mosby dominated the woods near Vienna, Virginia during the Civil War. This simplifies and detracts from the greater truth: a labyrinth of formally designed and informally deigned infrastructure created a warren of potentials. In the space between Difficult Run and Vienna, an ambush could emerge from any angle and dissolve just as easily into one of many corridors or lanes that channeled guerrillas to safety.

This aji and its kinetic expression had a terrifying aspect for any Yankees unlucky enough to experience its potency. Upon leaving Federal lines in any direction from the camp at Vienna, Union soldiers could rightfully expect to be set upon from any quarter, including and especially the rear.

Like the Ox Road and its tributaries to the south, the Lawyers Road and Hunter Mill Road intersection west of Vienna was a complex infrastructural palimpsest. Centuries—potentially millennia–of human travel carved the desires of successive populations into axial thoroughfares that shifted and settled to suit each generation until they were paved over in the 20th century.

Hunter Mill Road, like the Chain Bridge Road that ran from Vienna to Fairfax Court House, was regarded as an indigenous ridge road—a pre-cut trace lacing from high point to high point on a line that invariably connected the rich resource belts of Difficult Run to the popular pre-historic Potomac trading interface.[23]

As modern drivers can attest, the Hunter Mill Road north of Difficult Run bobs and weaves as it did through the 20th century, the Civil War, the early republic, colonial days, and the indigenous period. This road eventually connects with the Leesburg Pike, where both Lewinsville and Dranesville and their respective road hub networks were readily accessible. Frequented by Federal cavalry during the war, the Turnpike was an unsavory option for rebel raiders. However, modern Seneca, Springvale, and Beach Mill Roads would have offered potent escape potentials across the Potomac for knowledgeable Confederates who followed the Hunter Mill Road northwards.[24]

Running crossways to this early north/south corridor was the Lawyers Road or, more appropriately, the Lawyers Roads plural. Jim Lewis, Jr., historian emeritus of the area around Hunter’s Mill, charts the development of the Lawyers Road back to Col. Broadwater’s 1740s-vintage mill.[25]

The Lawyers Road was purpose built and precisely named. Fairfax County’s first courthouse was located in modern Tyson’s Corner. In the 1740s, a road built from potentially pre-existing parts was pieced together. It sprouted southwest from the courthouse towards the western leg of the Ox Road and then across field and forest until it reached the Braddock Road and the colonial road to Williams Gap.[26]

Today’s Lawyers Road reflects a 19th century modification of the original road. Another route to Vienna, Old Courthouse Road, follows parts of the original Lawyers Road, which would have connected Ayr Hill, as Vienna was known, to the Hunter Mill Road. Both of these thoroughfares—one in formal use and the other as an informal road remnant—were writ large on the local landscape during the Civil War.

It’s worth noting that the Old Courthouse Road intersected the Chain Bridge Road and then partially paralleled it on an alternative path to Fairfax Court House that approaches the county seat from the northeast on a line consistent with modern Nutley, Regents Drive, and Blenheim Boulevard. This potentially valuable road cut across much of the Moore and Hunter family properties, to which Mosby Rangers William E. Moore, Richard Farr Broadwater, and Guy Broadwater were related.

An examination of the 1862 McDowell Map reveals a still richer web of farm roads connecting these greater thoroughfares with local enclaves. Most prominent are the two “Old Wagon Roads” that cut between Hunter’s Mill and Lawyers. Many other dotted lanes track off main roads towards homesteads and bands of noted forest.

As Greg Weaver of Vienna Virginia History and Jim Lewis, Jr. of the Hunter Mill Defense League have rigorously documented, a road at Clarke’s Crossing of Piney Branch afforded locals the ability to cut across the run below Vienna.[27] The McDowell Map also indicates a similar ford road extending off one of the Old Wagon Roads.[28] This particular path goes on to dead-end at the Old Courthouse Road. On its western limit, this road charted across the land of many Mosby families before colliding with Hunter Mill Road on a line consistent with modern Vale Road.

This route was an important gateway to “Old Bad Road.” Similarly, Lawyers Road at Hawxhurst’s Mill just west of the Hunter Mill Road fed directly into “Bad Road,” better known today as the eastern limit of Stuart Mill Road. Both of these routes were maligned on Federal maps because they crossed some of the worst sloughs in Upper Difficult Run and often paralleled the creek in geography that lent itself to superlative mud.

However, both of these “bads” were perfectly situated to support a forward Confederate base of operations. Many friendly properties were located along both. Federals were unincentivized to use the roads at all because of their names. Best yet, with skilled use of these roads, Confederate partisans in deconstructed single file or loose group tactical configurations could pass across loyalist country and reach the Ox Road and the Little River Turnpike, from which they could readily access the belt of Mosby farms that dotted the western parts of Fairfax County.

These roads are the ones we know about. The old tale told of John Underwood, Mosby scout and Vienna familiar, was that he “knew paths not even rabbits had found.”[29] This paradigm was probably most true in the 8200-acre timber forests north of Lawyers Road. Benjamin Thornton, Scottish hardwood magnate, ran a successful prewar lumbering operation here. Despite the volume of production therein—Thornton and company were said to be utilizing twenty seven perpendicular saws to process their trees—much of the land remained wooded going into the war.[30] Underwood, a “woodsman” by trade, who had moved from his native Middleburg to the vicinity of Frying Pan, a neighborhood just west of Thornton’s holdingslikely knew these timber fields intimately.[31]

Crucially underappreciated in this calculus is a whole other set of roads. Creeks were local minima—flat lands that connected citizens to the mills where they were known to gather, take their mail, process their agricultural output, and drink. Further, it can be safely surmised that the saw mills on Difficult Run were receiving local raw timber from both highland and lowland neighbors. Those living and felling trees in the valley itself would not have been calorically incentivized to drag this hardwood timber up to a ridge road when a muddy skid along the creek to a nearby mill would have sufficed.[32] 1930s-era aerial imagery of the basin reveals predictable paths paralleling the creek and splitting off in either direction to climb through draws towards high land.

These creek parallels were the epitome of local knowledge. Desire paths and cut betweens, these convenient avenues would have been well known to local Rangers. I say this as a child of Little Difficult Run who spent a chunk of his boyhood riding his bike between neighborhoods on the formal and informal trails that blossomed off the creek.

To properly understand the available routes through the valley, a map of creeks and a map of Civil War period roadways should be overlaid. Add the torn up Alexandria, Loudoun & Hampshire railroad bed and you have a stunning map of potential movement that simultaneously demystifies that omnipotent Gray Ghost myth and adds subtly and nuance to the intelligence of John Mosby’s operations near Vienna.

MURDER

The many threads of this story tie together and telegraph through the ages in the form of one particularly auspicious incident: the murder of John D. Read by an unknown Mosby Ranger (potentially Bush Underwood) on the AL&H railroad tracks two miles west of Vienna on the night of October 18, 1864.

Read’s execution is a familiar piece of Mosby lore. Early on the 18th, a raiding party of rangers under Richard Montjoy infiltrated Accotink Creek by way of Centreville. Rebuffed by Federal guns at the Union stockade in Annandale, the seventy-five man detail turned northwards towards Falls Church. [33]

Around 2 a.m. the Confederates struck near Falls Church. Read’s Brother, Hiram, owned a modest property just northwest of the modern intersection of Lee Highway and Route 7. In 1864, Hiram’s home was adjacent to that of Daniel Sines, whose barn Federal cavalry utilized as a stable for their horses.[34]

With Bush Underwood serving as lead scout, Mosby Rangers were busy confiscating the Yankee horses in Sines’ barn when they heard a horn blow in the near distance. Montjoy and Company quickly realized that the noise was not a hunter flushing out game, but at attempt by a Connecticut-born local to summon local Federals. A firefight ensued, in which a free African-American named Frank Brooks was killed.

Read and another freeman were captured and brought to the woods west of Vienna where they were summarily executed. Or so Mosby’s men thought. Read was dead as a doornail, but his compatriot survived to tell the tale. Today, a ‘Terror on the Tracks’ historical marker interpreting the event along the W&OD Trail is witnessed by a host of cyclists passing in third gear.

Lost in this narrative is the salient question of how Confederate raiders were able to lace through a network of Yankee forts and patrols, before skirting a massive Federal camp, and arriving on the other side unseen where they felt comfortable enough to fire two pistol shots.

By 1864, the Yankee line along Chain Bridge Road was reinforced with another phase line running from Lewinsville to Falls Church and down to Annandale. Finding this too to be inadequate, Colonel HM Lazelle of the 16th New York Cavalry implemented in 1864 a “secret picket-line” near Falls Church. The tactic was a sort of early LRRP methodology built on small squads of six to twelve who would take two days rations and set up concealed posts in unpredictable quadrants to surprise Rebels.[35]

Given this defensive posture, it is stunning to think that Montjoy and his seventy-five man contingent would be so successful on that October night. The mystery—and with it the supernatural allure of John Mosby himself—fade somewhat as the spatial reality of friendly civilians between Vienna and Falls Church sheds new light on the incident.

Just west of Hiram Read’s farm, the land sloped downwards into Tripps Run, a ready-made corridor for escape where silhouettes disappeared. Less than a mile north, that creek peters out into its headwaters along the AL&H railroad. From there, it would have been a quick three miles along the railbed until a party of raiders intersected Frank Williams’ family farm, where a prominent hill afforded them a view over Vienna. The Follin family owned the adjacent farm. Both properties sloped into the deepening basin of Wolf Trap Creek, which crossed Chain Bridge Road at a very opportune low point just east of the Federal cavalry base. From there, it was a few hundred yards before the run ducked into the Follin Brothers’ father’s farm, which extended all the way to Courthouse Road. Following that for less than half a mile, Mosby’s men would have found Clark’s Crossing Road. This trace was surrounded by properties of Mosby families not far from the murder site a half mile to the west.

All in, this creek and railbed heavy route skirted every major Federal outpost in the area with just under nine miles of travel distance. The record of what occurred just after the murder of John D. Read seems to corroborate Wolf Trap Creek’s central role in the evening’s events. The party rode back towards Vienna from Difficult Run then captured the Federal cavalry picket at the intersection of the Leesburg Pike and the Lewinsville Road. That location was a mere one and a half miles directly downstream on Wolf Trap Creek from the place on the Follin Farm where the Old Courthouse Road forded that run.[36]

The spatial relationships that enabled and motivated the killing of John D. Read went even deeper. Fifteen months prior to his death, John D. Read offered Federal authorities knowledge of Mosby’s “Headquarters,” which he claimed was “only about 5 miles from Falls Church.”[37] It was five miles as the crow flew between Vienna and the home from which Read was snatched.

More intriguing still, another Federal informer, Charlie Binns, was potentially the procuring cause for southern partisans to be lurking in the woods near Falls Church. Binns had been an enthusiastic 1863 enlistee in Mosby’s guerrilla experiment before drunkenness and a supposed plot to re-enslave local freed women caused Binns to flee the command or face arrest.[38] He then did an about face and offered his considerable intelligence to Union cavalrymen. Subsequently, a price was put on Charlie Binns head and a rumor has trickled through oral history suggesting that Mosby would give a lieutenancy to anyone who brought Charlie Binns back for justice.[39]

Binns was married to Mary E. Gantt Rose, who owned a farm in Falls Church less than a mile to the west of Hiram Read’s house. John D. Read may have blown the horn that alerted Rebels to his presence, but the raid that cost him his life was potentially an extra-curricular effort to see if Charlie Binns was home. [40]

A BASE IN THE WOODS

The spatial coincidences presented above are proven facts. The idea that they interconnected in specific, meaningful, routed ways are theories. These particular theories are difficult to prove. Absent the discovery of a mid-19th century era teleportation device, these ideas represent one of the most plausible explanations of the geography that enabled the murder of John D. Read.

More facts facilitate still more theories. Indisputable is the fact that spaces mattered and the social, infrastructural, and topographic sinews that governed the inter-relation of these spaces mattered more than all. The configuration of these resources and their masterful manipulation by a Confederate guerrilla created a palpable sense of fear in Vienna.

This reality goes beyond the rhapsodic verse of Herman Melville. People—to wit, Federals and loyal civilians—who had to venture into the woods near Vienna from 1863 to 1865 were rightfully terrified.

Case in point: on the morning after her husband’s murder, the newly-minted Widow Read went unaccompanied to search for John’s body. The fear of Rebels still lurking in the forests was great enough to dissuade armed Federal cavalry from scouting two miles west of their fortified camp.[41]

Despite the fact that the Union cavalry camp at Vienna was less than thirteen miles from the White House and was buffeted by heavy Federal presence patrolling dozens of miles of roadway to the west, the area of Difficult Run near Vienna was ostensibly Confederate territory.

Quasi-permanent Rebel presence in this valley is a theory now as it was for Federals during the war. Three weeks after Read’s murder, Federal dispatches informed the cavalry commander at Falls Church of a “reported camp of Mosby’s men at Flint Hill.”[42]

This was a logical conclusion. One supported by a counter-intuitive body of evidence. Throughout 1864, Mosby and his men were harried and hunted all across their line. Savage combat along the Shenandoah, burning raids striking the very heart of the command’s formal base in Loudoun, and increased patrolling along the western boundary of Fairfax County did unquestionable damage to Mosby’s battalion. Yet, this group of guerrillas nominally headquartered near Upperville thirty-four miles distant, consistently projected across the Vienna line and into eastern Fairfax County.

On January 8, 1864, Confederates struck a Yankee picket post at Flint Hill.[43] In March, Mosby himself brought a detachment to bear a detachment against a 14-man outpost guarding Jermantown east of Difficult Run.[44] April 22 found Mosby and William Hunter leading three dozen men from Company A in an attack on the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry at Hunter’s Mill.[45] On June 5, Mosby and a crew of rangers including Bush Underwood staged an unsuccessful rendezvous in Fairfax County from which they hoped to penetrate as deep into Union lines as the Telegraph Road in Alexandria.[46] Company B—a unit rife with men from Hunter’s Mill and Vienna—raided near Fairfax Court House.[47] Mosby personally led a fifty man detachment into Fairfax on August 28. This unit split into three marauding units. Mosby commanded one, local boy Albert Wrenn commanded another, and the third under Harry Hatcher was supplemented by Bush Underwood.[48]

The murder of John D. Read on October 18 did not interrupt this pattern. Bush Underwood and twenty men struck a Federal wagon train one mile west of Vienna on December 19.[49] Underwood returned with William Trammell on February 5, 1865. Together they laid an ambush in the forests near Vienna.[50]

As the Army of Northern Virginia withered in the Petersburg trenches and Confederate maneuver across Loudoun and Fauquier Counties became less secure, attacks did not drop off in Fairfax County. The March 7th bushwhack near the Flint Hill stockade was but a small taste of Rebel operational capacity in the Vienna sphere. On March 12, fifty Mosby men struck the Federal position where the Lewinsville Road intersected the Leesburg Pike two miles west of Vienna. This was the same location above Wolf Trap Creek where Montjoy and company appeared in the hour after murdering John D Read five months prior.[51] That very day, Bush Underwood and Richard Farr Broadwater—cousin to the Hunters of Hunter Mill—guided a Mosby unit as far east as Bailey’s Crossroads.[52]

Given the larger tactical scenario in Northern Virginia, these late-war strikes deep in Fairfax County suggest local gravity. Seventy-five Confederates were unlikely to muster in the Blue Ridge foothills, ride hell bent for leather across contested territory, thread through an immense forest and then dart across the creek valleys of Fairfax County, strike Federals, take prisoners, and then wind their way back to Upperville. Simply, the elevated presence and enduring efficacy of these rangers suggests that Difficult Run was more than a waymarker. It was a base, a safe overnight space, and a step-off place.

Few places in Northern Virginia were so ready-made to serve in this role. Hidden trails, deep creeks, and impassable thickets jacketed with hardwood forests tied friendly properties together in a web that encircled the Federal camp at Vienna.

Long-neglected in favor of pastoral Loudoun and the rough-shod Shenandoah Valley, the woods near Vienna were a vortex of violence that served as the easternmost hub in Mosby’s Confederacy.

[1] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Serial 095, Page 0546-0549, Chapter LVIII, “Skirmish Near Flint Hill.” Ohio State University. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/095/0546

[2] Keen, Hugh C. And Horace Mewborn. 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry Mosby’s Command. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc, 1993. Pg. 137.

[3] Netherton, Nan, Donald Sweig, Janice Artemel, Patricia Hickin, and Patrick Reed. Fairfax County, Virginia: A History. Fairfax: Fairfax County Board of Supervisors, 1978. Pg. 526.

[4] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Serial 005, Page 0443-0445, Chapter LVIII, “Skirmish Near Vienna, VA” Ohio State University. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/005/0443

[5] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Serial 005, Page 0446-0447, Chapter LVIII, “Skirmish Near Vienna, VA” Ohio State University. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/005/0446

[6] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Serial 005, Page 0506-0508, “Operations in MD., N VA., and W. VA.” , https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/005/0506

[7] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Serial 016, Page 0270-0272, Chapter XXIV, “Operations in N. VA., W. VA., and MD,” https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/016/0271

[8] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Serial 018 Page 0803. Chapter XXIV. Correspondence, Etc.-Union.” https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/018/0803

[9] Alexandria Gazette: 1834-1974. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov> July 10, 1857. P. 3, col. 3.

[10] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Serial 016, Page 0087, Chapter XXIV. GENERAL REPORTS> https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/016/0087

[11] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Serial 040, Page 0504, Chapter XXXVII, N. VA, W. VA, MD., PA. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/040/0504

[12] RG 393, US Army Continental Commands, Part 2, Entry 4337, Letters Sent, 5th Army Corps, April 1863-April 1864. Citation and documentation courtesy of Bob O’neill.

[13] Greg Weaver of ViennaVAHistory.com has done further research on the ecological transformation that occurred near Vienna during the war. Through soldier accounts and post-war testimony to the Southern Claims Commission, Weaver has pieced together the thorough denuding of oaks and chestnuts from the area that became the Vienna cavalry camp.[13] This process surely extended beyond that acreage. Weaver, Greg. “Vienna’s Ayr Hill in the Civil War: Photos & Context.” April 16, 2023. Vienna Virginia History. https://viennavahistory.com/2023/04/16/viennas-ayr-hill-in-the-civil-war-photos-context/

[14] Alexandria Gazette: 1834-1974. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov> January 18, 1843. P. 3, Col. 6. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ndnp/vi/batch_vi_bees_ver01/data/sn85025007/00414215725/1843011801/0065.pdf

[15] Alexandria Gazette: 1834-1974. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov> January 2, 1863. P. 2, col. 1.

[16] Keen, Hugh C. And Horace Mewborn. 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry Mosby’s Command. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc, 1993. P. 6.

[17] O’Neill, Robert F. Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby. Jefferson: McFarland & Company Inc, 2012. P. 100.

[18] Ibid 206-207.

[19] Used with Robert F. O’Neill’s permission. The Litchfield-French Papers, Clements Library, Anne Arbor, Michigan.

[20] Hakenson, Donald C. And Charles V. Mauro. A Tour Guide and History of Col. John S. Mosby’s Combat Operations in Fairfax County. Fairfax: HMS Productions, 2013. Pg. 94-95.

[21] Ira and John Follin’s mother, Jane Louisa Lanham (1826-1915) was daughter to Margaret Adams (1798-1854) was brother to Samuel Adams (1792-1864) whose son was Charles Adams (1827-1877).

[22] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War. Serial 091, Page 0414-0415. Operations in N. VA, W. VA., MD., PA. Chapter LV. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/091/0414

[23] Evans, D’anne A. The Story of Oakton, Virginia: 1758-1990. Oakton: The Optimist Club of Oakton, 1991. p. 103.

[24] Crowl, Heather K. “A History of Roads in Fairfax County, Virginia: 1608-1840. Masters Thesis, (American University, 2002). Pg. 95. https://aura.american.edu/articles/thesis/A_history_of_roads_in_Fairfax_County_Virginia_1608–1840/23878788?file=41875287 This thesis has been an important touchstone for understanding the way that contemporary Fairfax roads are actually snippets of larger systems that ran through current developments to reach distant destinations.

[25] Lewis, Jr., James, and Charles Balch with Kenneth Jones. Forgotten Roads of the Hunter Mill Corridor. Oakton: Hunter Mill Defense League, 2010. Pg. 9.

[26] Crowl, Heather K. “A History of Roads in Fairfax County, Virginia: 1608-1840. Masters Thesis, (American University, 2002). Pg. 53.

[27] Weaver, Greg. “Clark’s Crossing Road West of the WO&D: A Short History.” Vienna Virginia History. March 5, 2023. https://viennavahistory.com/2023/03/05/clarks-crossing-road-west-of-the-wod-a-short-history/

[28] Map of n. eastern Virginia and Vicinity of Washington. General Irwin McDowell. 1862. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3881s.cw1009001r/?r=0.284,0.257,0.438,0.262,0

[29] Jones, Virgil Carrington. Ranger Mosby. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1944. Pg. 90.

[30] “Ship Timber.” Alexandria Gazette. April 20, 1857. Pg. 3, Col. 3. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ndnp/vi/batch_vi_drive_ver01/data/sn85025007/00414215968/1857042001/0522.pdf

[31] Source for John Underwood as a woodsman: Seipel, Kevin H. Rebel. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983. Pg. 78. For the family’s move from Loudoun to Fairfax, see the disparity between the 1840 and 1850 census.

[32] Probably my favorite rendering of this informal path-making process comes from an 1856 real estate advertisement. MC Klein marketed his property on Difficult Run in the valley west of Hunter Mill Road as “bounded on the west by Difficult Run, on which there are Merchant Saw-Mills of convenient access; also, abundantly supplied with timber of original growth.” Alexandria Gazette: 1834-1974. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov> March 3, 1856. P. 3, col. 7.

[33] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War. Serial 091 Page 0414 Operations in N. VA., W.VA., MD., AND PA., Chapter LV. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/091/0414

[34] Mitchell, Beth. 1860 Fairfax County Maps. 1977. This story is often muddled to suggest that John D. Read was snatched from his own home, which was not, in fact, true. John lived at Bailey’s Crossroads. Hiram, his brother, lived in Falls Church, adjacent to Daniel Sines.

[35] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War. Serial 071 Page 0387-389 OPERATIONS IN N.VA., W.VA., MD., AND PA. CHAPTER XLIX. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/071/0387

[36] Keen, Hugh C. And Horace Mewborn. 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry Mosby’s Command. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc, 1993. Pg. 202.

[37] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War. Serial 049. Page 0026. OPERATIONS IN N.VA., W.VA., MD., and PA. Chapter XLI https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/049/0026

[38] Johnson II, William Page. Brothers and Cousins: Confederate Soldiers & Sailors of Fairfax County, VA. Athens: Iberian Publishing, 1995. 16-17.

[39] Hakenson, Donald C. And Charles V. Mauro. A Tour Guide and History of Col. John S. Mosby’s Combat Operations in Fairfax County. Fairfax: HMS Productions, 2013. Pg. 119

[40] Mitchell, Beth. 1860 Fairfax County Maps. 1977. https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/history-commission/sites/history-commission/files/Assets/documents/1860CountyMap/50-1.jpg

[41] Lewis, Jr., James, and Charles Balch with Kenneth Jones. Forgotten Roads of the Hunter Mill Corridor. Oakton: Hunter Mill Defense League, 2010. p. 22.

[42] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War. Serial 091 Page 0539 Chapter LV. CORRESPONDENCE, ETC. – Union. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/091/0539

[43] The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War. Serial 060 Page 0365 Chapter XLV. CORRESPONDENCE, ETC. -Union. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/060/0365

[44] Keen, Hugh C. And Horace Mewborn. 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry Mosby’s Command. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc, 1993. P. 116

[45] Ibid 119.

[46] Ibid 131.

[47] Ibid 147.

[48] Ibid 167.

[49] Ibid 234.

[50] Ibid 244.

[51] Ibid 250.

[52] Ibid 251.