TL;DR–Patterns of indigenous use etched a profoundly influential template on the landscape of the Difficult Run Basin.

Narrative Event Horizons

Roads are patterns. Habitual human behavior carves itself into the earth. We barely notice. It’s a monumental paradox.

“An axis is perhaps the first human manifestation; it is the means of every human act,” writes Le Corbusier in his Towards a New Architecture.1 Mighty important as axial roads are, they are essential to the point of invisibility. It’s a phenomenon ethnographer Susan Leigh Star studied in depth. Vital infrastructure is typically invisible until the point of breakdown.

In the case of all critical components of civic engineering—sewage flows, power corridors, and especially roads—Star hints that any study requires “looking for these traces left behind by coders, designers, and users of systems.”2

Fairfax and Loudoun Counties preserve a wealth of records regarding the formation of modern roads whose roots and traces stretch back as far as the colonial era. Unfortunately, to excavate the work of the original “coders, designers, and users” of Fairfax County roads, we need to punch through a bias boundary.

In the preface to the 1986 edition of his historic monograph on the Potomac River, Frederick Guttheim promises coverage of “the entire river basin, with its three hundred and fifty years of human history.”3 If that phrase ever made sense in 1949, it’s an especially bad look now.

The blank slate fallacy is a tired borrow from the earliest rhetoric attached to European colonization. In the publicity drive calculated to heighten participation in the pyramid scheme of near-slave labor required to make the early colonies viable, English boosters promulgated a bunk and conniving narrative of virgin wilderness yearning to enrich hard-working yeomen.4

The mythos of unifocal European creationism endures. It slants histories of design and development in Northern Virginia. Pervasive bias couples with a want of indigenous records to create an event horizon at European contact. What transpired before was formative and yet unknowable.

Still, its crucial to acknowledge that European civilization—especially in Northern Virginia was not a first build. It was a graft. Archaeological evidence in the Upper Difficult Run Basin alone suggests that as many as eight thousand years of human prehistory shaped the land.

Indigenous migrations, site selection practices, and resource acquisition patterns established the original parameters for European settlements. This largely glossed-over and wide-spanning chapter in spatial history exerted an inordinate influence on what transpired after.

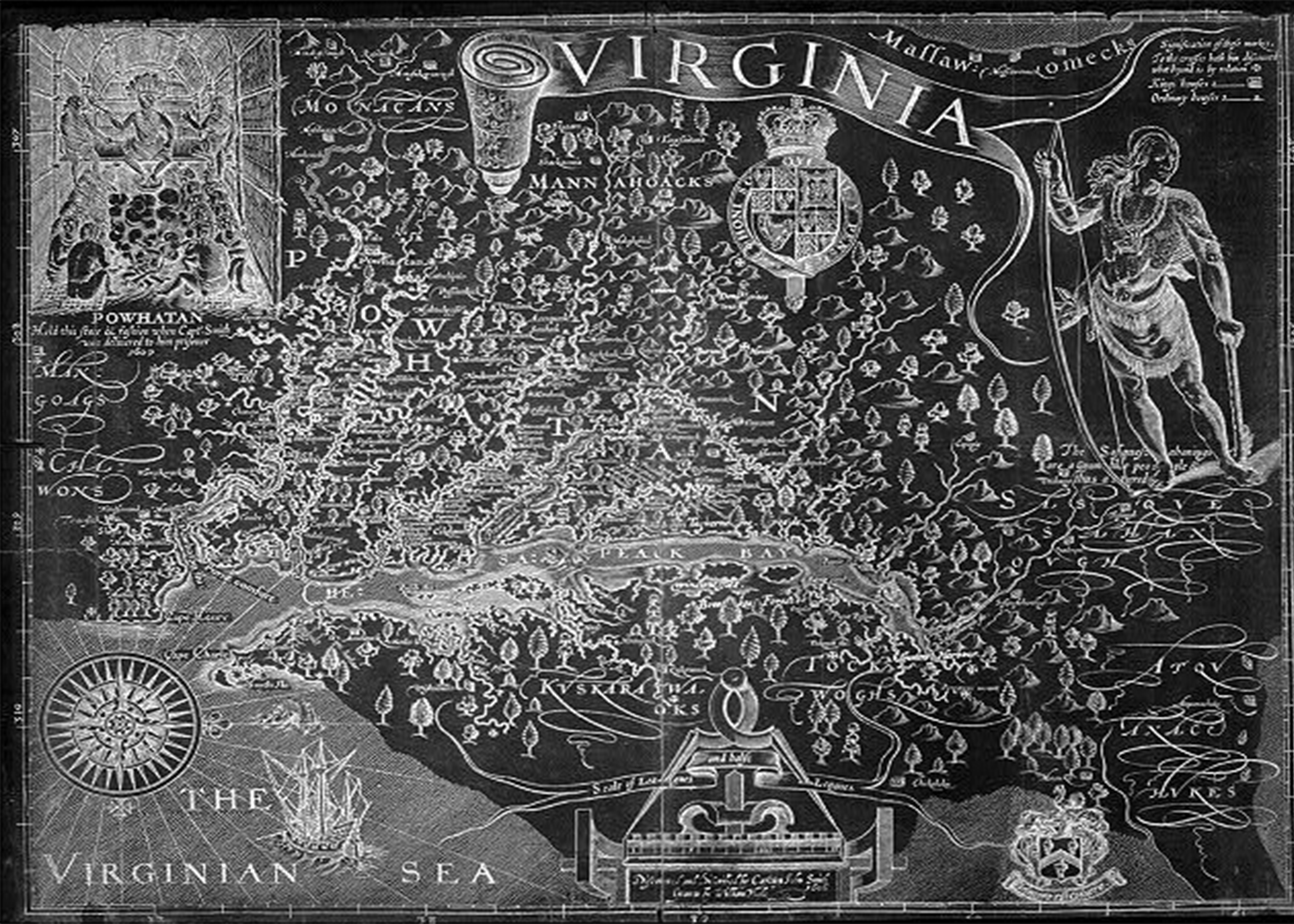

In Fairfax County, “history” begins in June 1608 when John Smith undertook an expedition up the Potomac River in search of precious metals.5 Smith spent a season exploring the Potomac. When considered against the rich body of archaeological records denoting thousands of years of lived time, Smith’s moment along the Potomac was an interval of time equivalent to a single frame of film in Lawrence of Arabia. The distortion is obvious, but nonetheless, the adventurer’s account became the definitive account of the indigenous world along the Potomac.

Smith was diligent in capturing a sense of the riverine world on which Algonquian-speaking people of future Fairfax County built their society. In this far corner of the Powhatan world—known to its inhabitants as Chicacoan—Smith recalls a society built to integrate with the great Potomac River and the many creeks that fed it.6

River People

Shellfish and lowland agriculture fed villages set just off the river on hillsides that overlooked broad creeks that flowed into the Potomac. These hydrological features were critical. In the age of the canoe, waterways were highways. This partially-true hypothesis makes sense to a transcontinental explorer like John Smith who privileged travel by boat in his own worldview. Especially given his membership in a world cut from a fabric woven together from diplomacy and wealth.

Chicacoan was nominally allied to the Powhatan Confederacy. Still, its distance from the werowance, or chieftain, afforded this district a unique set of opportunities and challenges. “Potomac” is apparently an Algonquian word for “something brought.”7 The people that John Smith encountered across the Potomac River for the future site of Washington, D.C. specialized in trade. They belonged to a confluence culture, facilitated by a marriage of river access and proximity to the fall line where Iroquois-speaking people, including the Susquehannock, similarly trafficked in specialized resources.8

This reality presents a more nuanced idea of place-use in Algonquian culture than that presented by John Smith. They did utilize the rivers for transportation, defense, sustenance, and trade. This watery-road network offered invaluable access to the south, but was hindered immediately to the northwest by the fall line.

In order to facilitate trade, the Doge and Patwomekes inhabiting present day Fairfax County would necessarily have enjoyed a built interface with the interior that was independent of river access.9

Smith himself teased a “beyond” that connected river-adjacent primary villages with resource camps in the distant hinterlands. Having communicated his thirst for rare earth, natives led Captain Smith to the site of a prominent ore quarry some seven or eight miles from the river.10

An existing network of paths and roads was apparently already cut into the landscape by the time natives utilized one to bring Captain Smith to an established resource extraction site. It is this infrastructural system on which much of the colonial English world in Fairfax County was transposed.

Land Orientation

Its most important vestigial trace could be found well into the 19th century with the common usage of the term “ridge road.”

Historian Donald Sweig—one of the much beloved narrativists who collaborated with Nan Netherton to authoritatively document the County’s past—charted Colonial-era infrastructural growth along basic criteria.

“As the roads developed,” Sweig wrote, “they frequently followed old Indian or animal trails or the line of least resistance along the top of natural ridges.”11

Precise, but tautological to the max, Sweig’s formulation neglects to mention that Indian trails, animal paths, and “ridge roads” were often one in the same. Elsewhere in the historical record, in fact, the term “ridge road” is used almost synonymously with Indian path. We are meant to understand that indigenous people and their animal predecessors cut the first crest line paths trails that English colonists used to inject themselves into the countryside.

In 1952, Katherine Snyder Shands assembled the theory from abundant folk knowledge and oral history for a piece in the Historical Society of Fairfax County’s Yearbook.

Shands offers the interspecies theory of road origin as follows, “The inland roads began as the trails of the buffaloes going from their pasture lands along the river, over the Blue Ridge, and into the Valley. Over these trails went the Indians, and after them the earliest explorers and fur traders. As men and animals instinctively seek the course of least resistance, the trails followed the ridges of the hills by the easiest grades, and later the roads followed over them. These roads were used by the new settlers, who, finding no room along the rivers, went to the Piedmont and over the mountains; and it is these same roads which carry over Fairfax County the swift traffic of today.”12

Later sources more oriented to the immediate confines of Difficult Run are more explicit in conflating native paths with geographic opportunism.

D’Anne Evans’ history of the hamlet of Vale—a mostly forgotten post office-designated community in the heart of the Upper Difficult Run Basin—treats both Hunter Mill Road and Chain Bridge Road as “two Indian ridge trails.”13

Patricia Strat, Evans’ successor and an eminently qualified and prolific historian in her own right, identifies Ox Road (today’s West Ox Road) as an Indian trail and ridge road in the appendices to her monograph on the community of Navy.14

The Hopkins Map of 1879 depicts a section of today’s Reston Parkway that unites with the once and former Ox Road as a “Ridge Road.” This thoroughfare bridges the gap from the northwest edge of the Difficult Run watershed through Dranesville all the way to the Potomac.15

We’re left with an understanding that the area surrounding Difficult Run was bounded by high ridges which were already established as transportation corridors before the arrival of European colonists. Curiously, all three of these Indian ridge roads—West Ox with its later northern Ridge Road corollary, Hunter Mill, and Chain Bridge—connect known stone quarries with the Potomac River.

Lithic Determinism

In 1728, Robert “King” Carter patented land at a site known as “Frying Pan” in the western reaches of Fairfax County. It sat on a plain accessible by both forks of the known Ridge Roads that ran along present West Ox Road. In fact, the designation “Ox Road,” by which this avenue came to achieve colonial prominence, denoted the path as the axis of outflow for the Carter’s mining operation at Frying Pan.16

Originally thought to be a rich vein of copper ore, the rock discovered at Frying Pan was assayed in London as little more than green sandstone. A worthless asset in the alchemy of trans-Atlantic mercantilism, but part of a rich complex of triassic sandstones whose use bridges prehistoric Virginia with colonial extraction and contemporary Washington, D.C.

Local natives utilized that category of stone in carvings.17 Colonists attempted to mine and monetize it. Modern architects privileged its use in monumental building for structures in the nation’s capitol.18 The particular seam of viridescent stone at Frying Pan was largely a bust, but one that is not coincidentally connected via established pathways to a trans-Potomac world build on the trade of rare or alluring resources.

More intriguing still is the case of modern Chain Bridge and Hunter Mill Roads, both of which follow courses from known fords over the Potomac to an intersection point half a mile from an important deposit of stone that native people prized for its use in tools and points.

What came first? Knowledge of the discovery of strong vein of white quartz near modern Marbury Road in Oakton, Virginia, or the ridge roads that led there? By the time English settlers arrived, the pocket of valuable igneous stone was well known. To the point that the town of Oakton first assumed the name “Flint Hill,” a name it carried through the Civil War, because Europeans mistook the already well-quarried stone for valuable flint.19

They were mistaken and disappointed. What’s critical here goes beyond the disappointment of metallurgically-aware Europeans. A complex of indigenous people whose archaeological record is strewn with white quartz tools built two separate axes connecting trade routes with a quarry site rich in white quartz.2021

Prehistoric records are very difficult to document and much more challenging to speculate about accurately. Nonetheless, the high ground surrounding Upper Difficult Run presents an interesting theory about indigenous lithic determinism and the roots of place development.

Valley Roads

This world of high roads and heavy stone and its predominance over road creation theory in Fairfax County has flaws. Chiefly, it owes much to the original John Smith theory of riverine people. Their world and our imagination of it privileges high ground on which trade parties could perhaps snatch valuable rocks to trade across the river.

It’s only half of the story.

Before we find ourselves fully seduced by the oysters and spear points view of Potomac pre-history, we do well to soak in the mysteries of a duality-rich world until the skin on our fingers prunes.

From this tepid bath, an important question bubbles up from the drain: doesn’t the term “ridge road” imply the existence of non-ridge roads? Is it safe to assume there were also valley roads? Or were the first residents of modern Fairfax County too prim and proper to muddy their feet in the marshy bottoms?

The answer is complicated—chiefly because archaeological resources in Fairfax County and Virginia at large are treated as protected assets. Their is no publicly-available database of sites within Difficult Run that can be indexed, mapped, and analyzed.

We’re left to eat around the edges, so to speak, on a table set by former Fairfax County Park Authority archaeologist, Michael F. Johnson. An enthusiastic student of pre-history, Johnson festooned the public record with important breadcrumbs highlighting the indigenous past along the upper reaches of Difficult Run.

Among Johnson’s clues are tantalizing hints about an abundance of chips and flakes found throughout the Fox Mill communities, which augment sites discovered near Franklin Farms, Pender, and the triangle between Jermantown Road, Waples Mill, and Route 50.

There are also accounts of a three-quarter greenstone axe dating from the period between 2000 BC and 1600 AD discovered near Quay Road above Stuart Mill and a hunter/gatherer site from 4000 to 6000 BC found “in the vicinity of Fox Mill and Hunt Roads.”22

Johnson and others devoted an immense amount of time and effort into the study of upland “procurement sites” and “temporary camps.”23 The work is an important step in adding dimension to the “oysters and canoes” impression of indigenous life along the Potomac.

The Karell and Dead Run sites—cherished laboratories for Johnson’s work—provide an interesting case study of inland valley life. Debitage excavations reveal little in the way of riverine food stuff. Both sites are also rich in quartz points. More intriguing still, the location of each is nestled along upland hollows just off of or proximal to alluvial fans or headwater floodplains.24

This position is significant in two ways.

First, it either duplicates or anticipates the same site selection pattern documented by John Smith and his colleagues as early as 1608. To quote Strachey, a fellow explorer of Smith, regarding the location of Algonquian sites on the Potomac, “theire habitations or Townes, are for the most part by the Rivers; or not far distant from fresh springs commonly upon the rise of a hill, that they made overlook the river and take every small thing into view which sturrs upon the same.”25

Fresh water was likely not a position determinant for inland procurement sites, but strategic high ground feels significant. The sites Johnson alludes to in Difficult Run—those between Route 50 and Waples Mill, on Quay Road, and in the triangle of modern Vale, Fox Mill, and Hunt Roads—all sit on high ground where present hardwood forests overlook either Difficult Run or Little Difficult Run while still maintaining a less-than-visible posture from the creek valleys below.

By nature, temporary camps beyond semi-permanent villages balanced essential opportunity with common hazard. In an area known as a contested liminal space between sometimes rival indigenous groups, rich forests overlooking fertile floodplains would have been prized possessions.

This illuminates the second crucial hint. Sites that potentially span nearly eight thousand years of human history in the Difficult Run area also bridge two separate resource paradigms: hunting/gathering and early agriculture. Not coincidentally, the site selection practices of Algonquian people in Difficult Run situates their procurement camps at the exact interface where collection zones intersect with cultivation zones.

People Gotta Eat

Assuring caloric competency requires procurement strategies that are necessarily flexible. Rigidity in practice does not seem to be something indigenous people of the eastern United States could afford. Instead, an agile mentality woven from experimentation and innovation seems to be the norm.

Earliest sites, like the hunter/gatherer camp that Mike Johnson explored near Fox Mill and Hunt Roads, benchmark the beginning of a cultural-culinary survival complex, one that responds to broad and sweeping climactic change.

Cooler weather patterns with long, oppressive winters phased out in favor of warming periods that invoked a groundswell of change in the biome.26 A sample study conducted at the Cliff Palace Pond site in Kentucky is illustrative of larger trends in mid-latitude North American Forests. Spruce and northern white cedar trees that were dominant in the Early-Holocene some eight thousand years ago declined in favor of hemlock, which in turn gave way to eastern red cedar some five thousand years ago. Beginning around the time to which Johnson’s dates the greenstone axe found on Quay Road, mixed oak-chestnut and pine forests became dominant.27

The oak/chestnut/hickory complex is a vital hint. These trees are more fire-tolerant to their predecessors and their preeminence in forests of a certain time suggests the emergence of anthropocentric fire regimes that groomed the landscape with intention. Motivation for any would-be fire starters of the mid-Holocene is clear: oak, chestnut, and hickory trees produce mast, or nuts.28

This forage-able resource was an essential component of early indigenous diet. A hickory grove of an area 1.2 kilometers in diameter could feed a family of ten for a year.29 Beyond direct impact, mast was also an indirect boon to these people. Wild hogs and other sources of huntable meat fattened on fallen acorns and chestnuts.

In his memoir, Country Boy Gone Soldiering, George Henry Waple, III, who grew up around his family’s mill on Difficult Run in the 1920s and 1930s remembers an abundance of mast. He recalls collecting nuts from the many chestnut trees that lined the valley and hills around his home and also details a bounty of nuts harvested from “bushes” that he referred to as “chinkapins.” Castanea Pumila, the Allegheny Chinquapin, was itself an important contributor to pre-historic foraging diets.30

The same fire clearance strategies that thinned upland forests of unproductive tree guilds in favor of mast-producing hardwoods also facilitated hunting and eventually came to be a known pillar of Algonquian cultivation strategies. John Smith provided accounts of tree stumps deliberately set ablaze in order to both clear and fertilize eventual maize production.31

In the bottoms below these fertile forests, prehistoric indigenous groups of the eastern United States learned to lean heavily on the chaotic confluence where fire, water, and earth achieved fecund symbiosis.

Long before the gradual trial-and-error invasion of maize from meso-America, long processes of experimentation brought the floodplain to preeminence in Native resource strategies. Known alternately as the “mudflat hypothesis” or the “floodplain weed theory,” Bruce Smith’s ideas about archaeobotany center around mid-Holocene patterns of alluvial deposit. Gone were far-spaced episodes of flooding. Instead, more consistent geographic and chronological patterns of “aggradation and stabilization” created consistent river and tributary valleys.32

Routine flooding churned creek-adjacent lands and flooded them with rich silt that encouraged the production of edible weeds like squash, sunflower, marsh elder, and chenopod.33 More than fire-cleared hillside meadows, bottom lands that had been swept of vegetation and reseeded by edible weed-friendly happenstance emerged between critical foraging districts.

Where mast-bearing trees of an area 1.2km in diameter could feed a family of ten for a year, 16,000 square meters of floodplain chenopod would provide the same sustenance.34 Eventually, these patterns of foraging took on a deliberate, programatic nature, with seed selection, culling, and intentional cultivation replacing happenstance.

This is quite literally academic. On a very practical level, however, a place such as modern day Oakton, Virginia, which is named after its wealth of mast-producing trees, is also quietly littered with indigenous sites that sit astride two important patterns of life-sustaining resources. Natives spanning thousands of years set up temporary camps on wooded hillsides overlooking creeks.

With deliberate site selection, indigenous people both overwatched and integrated diversified caloric landscapes, while simultaneously maintaining a strategic eye on the main axes of travel.

Foot paths—the first roads and the essential predecessors to the “bridle-paths” of the 1860s—united resource geographies by tracing longitudinal lines along forager-friendly creeks and bisected these water ways on axes that utilized natural clefts in the landscape. The most advantageous of these routes connected native peoples to ridge roads and still more essential lithic deposits where cultivation and processing tools like quartz were readily available.

Glimmers of Proof

In Difficult Run, the earliest document of such paths arrived woefully late with the 1937 aerial survey. By this point two centuries of European influence had contaminated the purity of any original paths that may have forked from the ridge roads down into the valley. Still, interesting patterns remain.

Just west of Marbury Road where “Flint Hill” drops into the valley behind Fox’s Lower Mill, white fractures in the landscape attest to patterned footfall. Paths partner and travel along the creek at near intervals and in parallel near the edge of the existing woods—an interface where deer and other prey are known to favor. These paths fork at opportune moments. They rarely, if ever, dart up a hill at its most drastic and impregnable height.

Instead, the cross axes travel through drainage draws and cuts past and beyond nearby hillside sites that early foragers would have found suitable. In this way, fingers of opportunity dating to a mysterious past, dart across the woods and fields in ways that were and will never be rendered on maps, except in their truest form—as creeks and local minima.

The key to John Mosby’s successful navigation of this basin is found in the meanderings of pre-history. For millennia, people have come to this place to sustain themselves. They have traveled in a way that marries convenient opportunities of landform with the abundant necessity of bridging high forests and low floodplains.

These patterns repeat ad nauseam and predict other spatial requirements negotiated by Confederate guerrillas thousands of years later. Where forested heights intersect long, sprawling creeks, we find spatial opportunities that transcend any one time period.