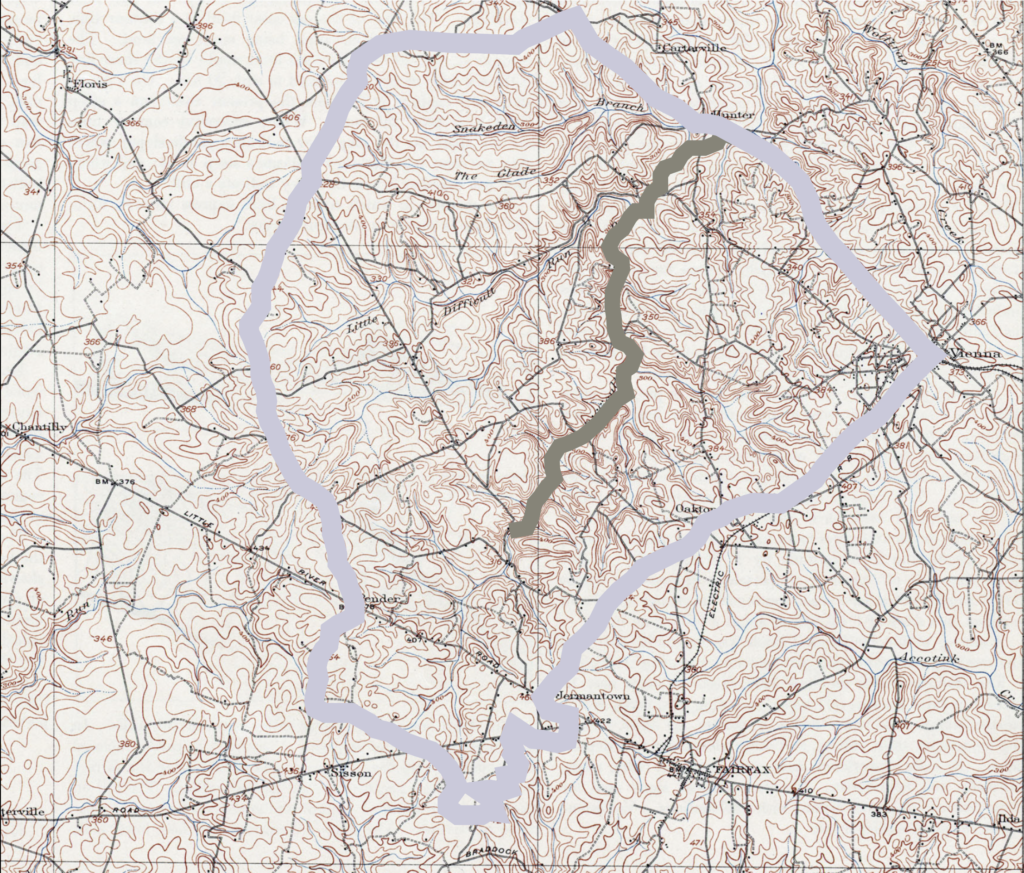

tl;dr–Mosby’s activities along Difficult Run were at their most intense between February and October of 1863 on a 4.4 mile-long line connecting Fox’s Lower Mill with Hunter’s Mill

“MOSBY” vs. Mosby

The legend of John Mosby—the Gray Ghost—sometimes has the feel of a shell of fabrications shellacked around a robust kernel of truth.

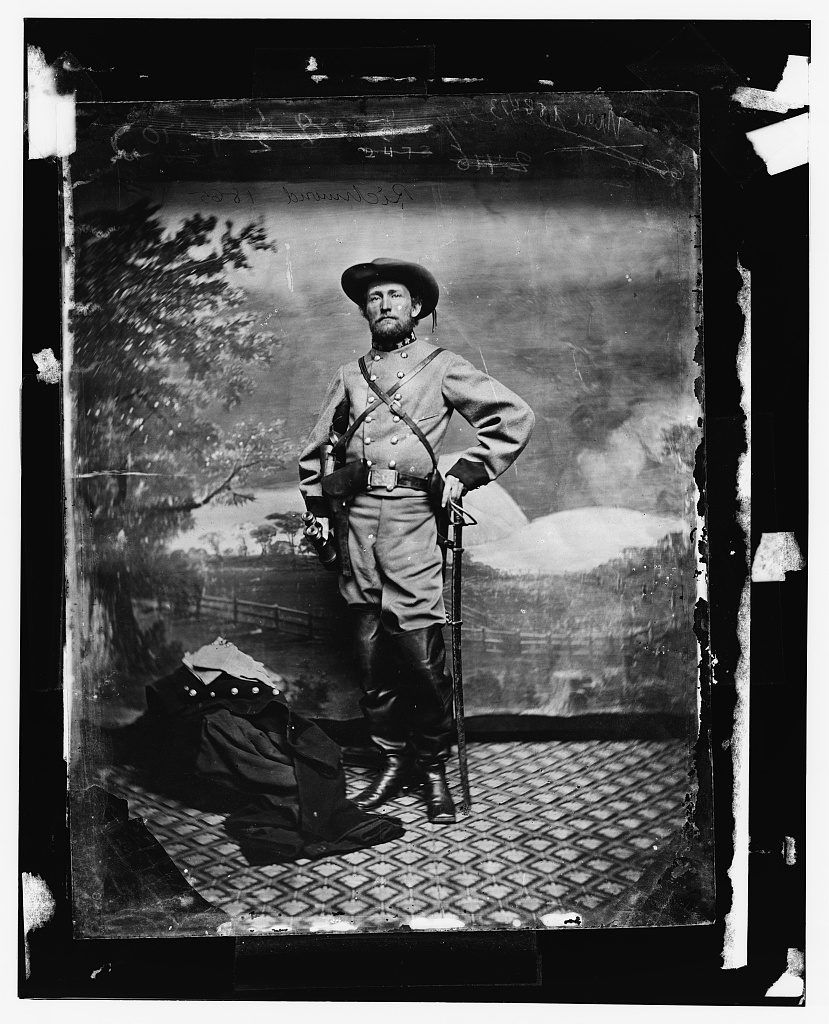

Lieutenant Colonel John Singleton Mosby was undoubtedly a brave, capable, and accomplished soldier. His actual exploits in the saddle are well-documented. For over two years, he and his band of irregular cavalry engineered a complex cat-and-mouse game designed to fix 50,000 federal troops in almost four hundred square miles of Northern Virginia where they could not contribute to the Army of the Potomac’s attempts to destroy Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

The game for Mosby scholars is to parse out what Mosby actually did from what he has been credited with doing.

It’s a phenomenon not unlike the case of the Vietcong a century later. “Charlie” became a catch-all nom-de-guerre for the efforts of a wide-ranging group of allied soldiers whose collective success lent itself to the imagination of an omnipresent enemy.

Beginning in January of 1863, the name “Mosby” functioned in much the same way for citizens and soldiers stationed in Northern Virginia. It referred less to a single man than to a wide category of hit-and-run attacks.

This broad fabric of violence often included simultaneous attacks staged dozens of miles apart. Unless John Singleton Mosby was blessed with Santa Claus-esque omnipresence, his participation in everything for which he is credited is unlikely.

It’s worth noting that the most-recent roster for the Mosby Rangers (alias: 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry) features no less than 1,881 names.1 This figure represents more men than someone in Mosby’s position could ever direct in a single battle. Especially in an asymmetrical combat environment where small groups of men gathered to initiate brief raids.

Simply put, John Mosby wasn’t present every time his men fought.

That obvious fact doesn’t even begin to account for the actions of other Confederate guerrilla units who operated in Mosby’s area and were mistaken for his men. Elijah White’s 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry, the Iron Scouts of the 2nd South Carolina, and the Black Horse Cavalry of the 4th Virginia were all active in the vicinity.2 Other units like the Prince William or Chinquapin Rangers acted independently for long stretches of time before eventually folding in to Mosby’s Rangers.

In official records and the mind’s eye of the federal soldiers that these units terrorized, the unknown assailants were none other than Mosby himself.

The distortion continued well into the post-war period. By the end of hostilities, “Mosby” was a well-known brand and having fought him was a badge of honor that carried immediate name recognition.

It’s a safe bet that many of those who trafficked in “Mosby” stories after the war had never met the man himself. In one instance, the memoirs of former Fairfax County sheriff and devoted Yankee scout Jonathan Roberts touted the unlikely distinction of having fought “Mosby’s guerrillas” ten months before Mosby’s guerrillas ever existed.3

Though premised on a wealth of untruths, the Mosby legend is an important part of historiography. The tall tales that surround John Singleton Mosby are both a testament to the efficacy with which he marauded the American consciousness and also one last cloak of secrecy veiling his true deeds.

The Critical Interval

Piercing this mythic veil is essential.

The real challenge—one that 50,000 Federal troops were not capable of achieving—is to pin John Singleton Mosby at a single point in time and space.

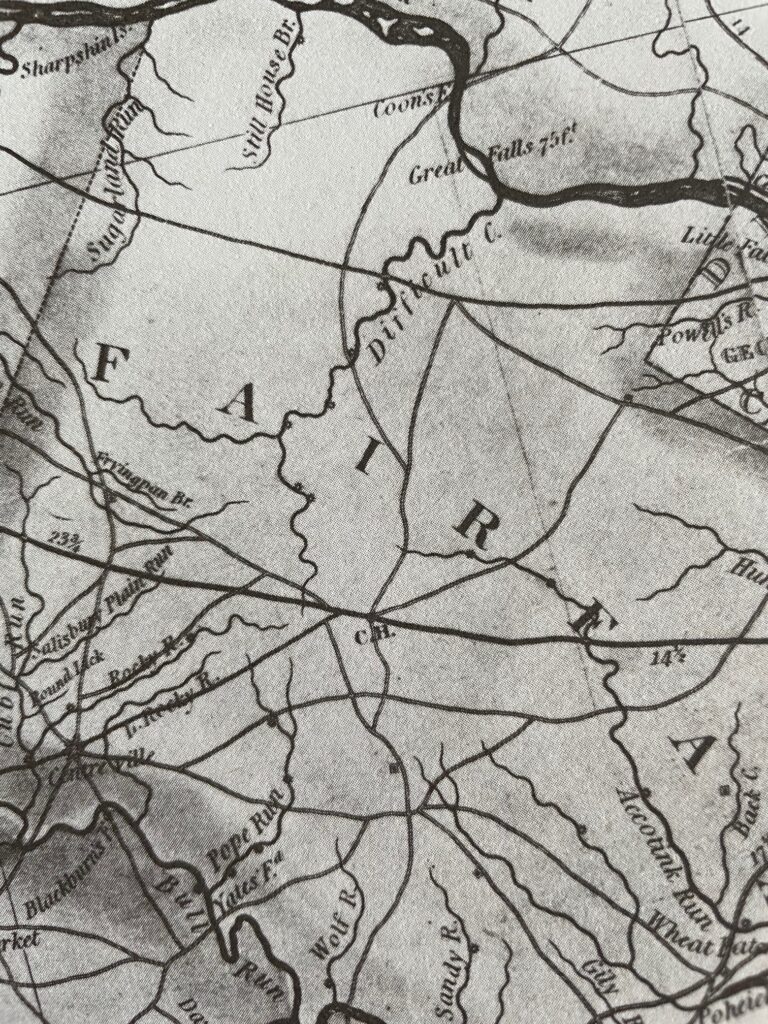

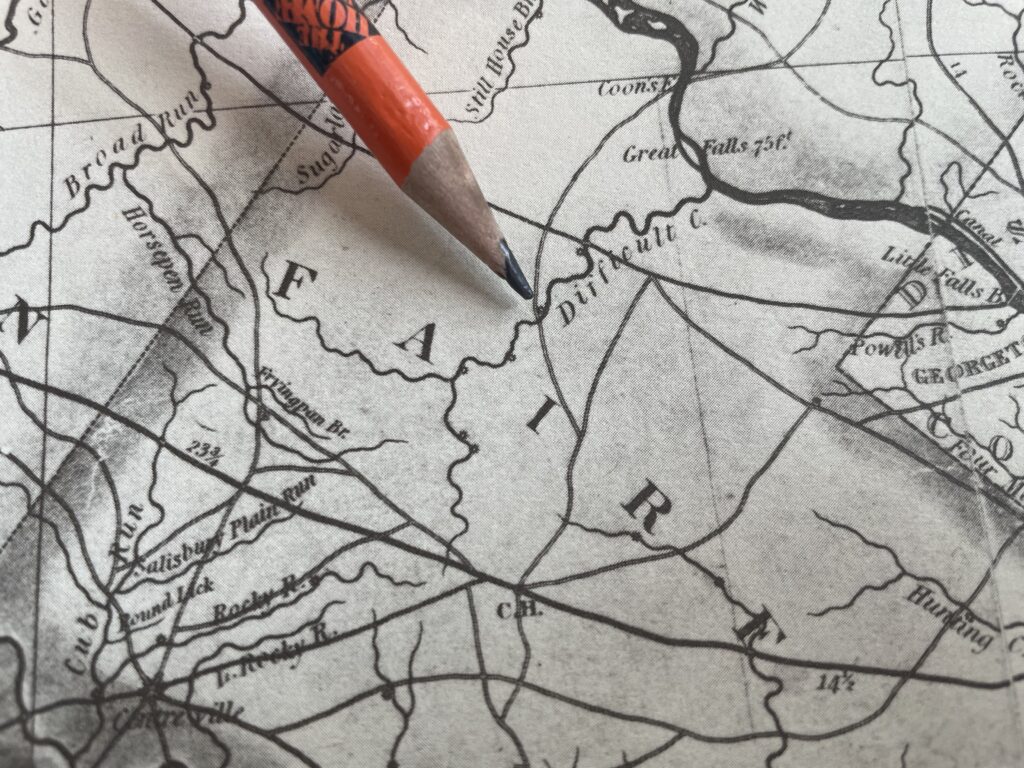

I’m looking to winnow down a massive body of geographic and temporal Mosby lore into a tighter envelope. Even in the context of this project, which deals chiefly in the time span between January of 1863 (when Mosby’s command was chartered) and April of 1865 (when Mosby capitulated) and the nearly fourteen square miles of space forming the Upper Difficult Run Basin, the coordinates are almost too broad for meaningful analysis.

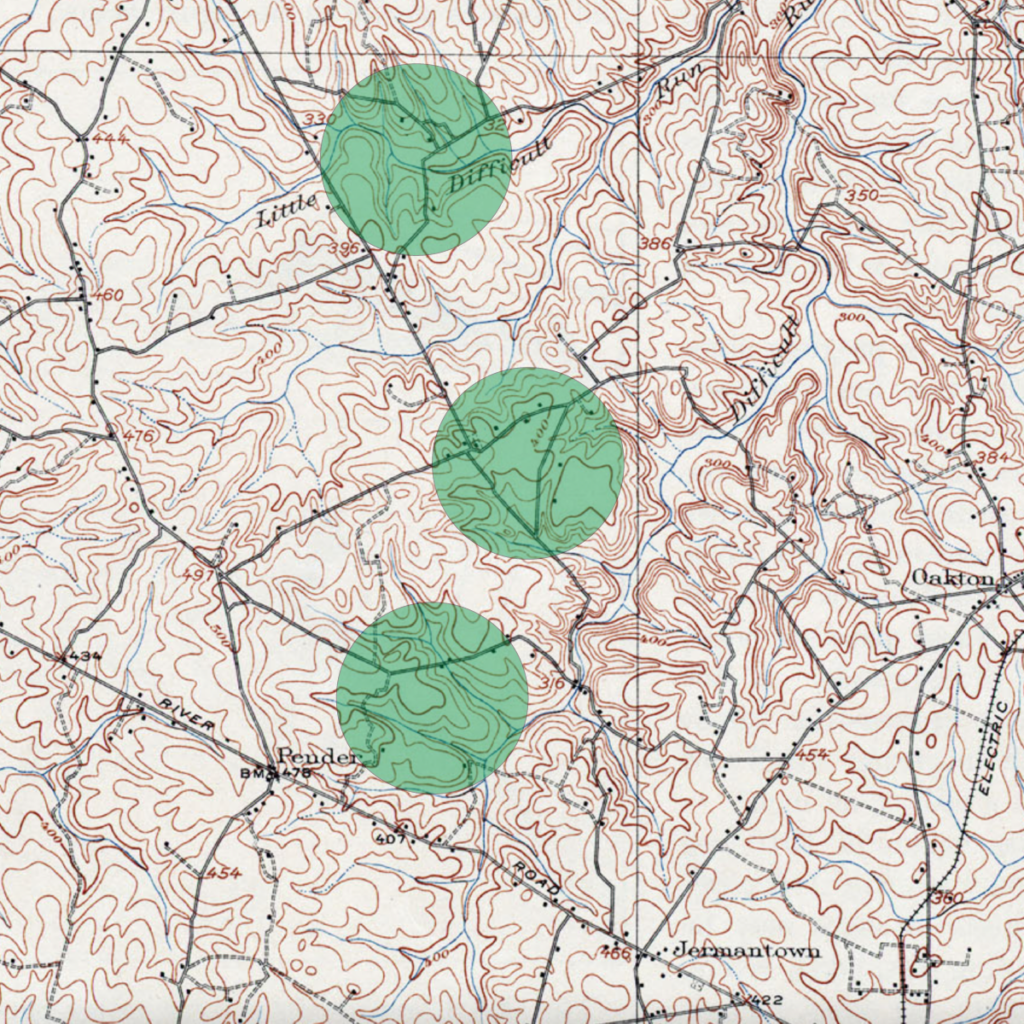

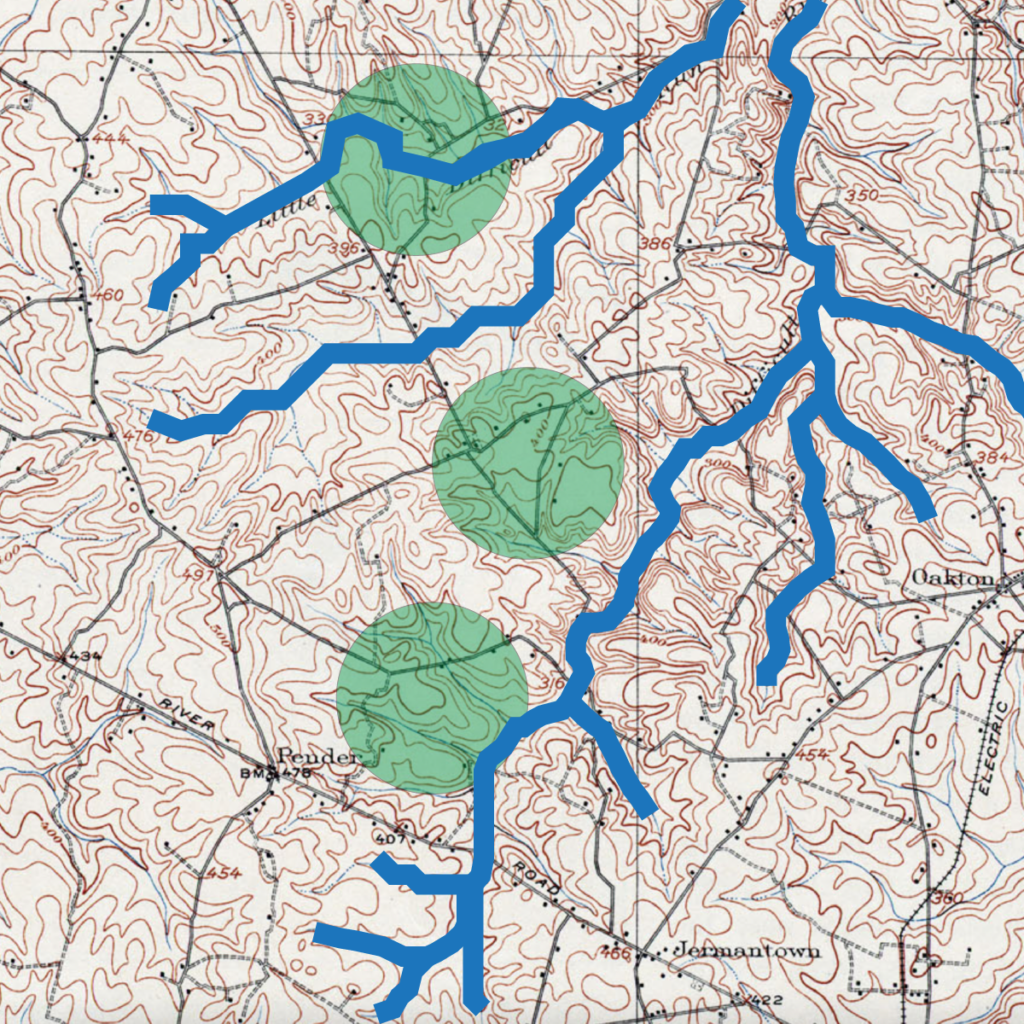

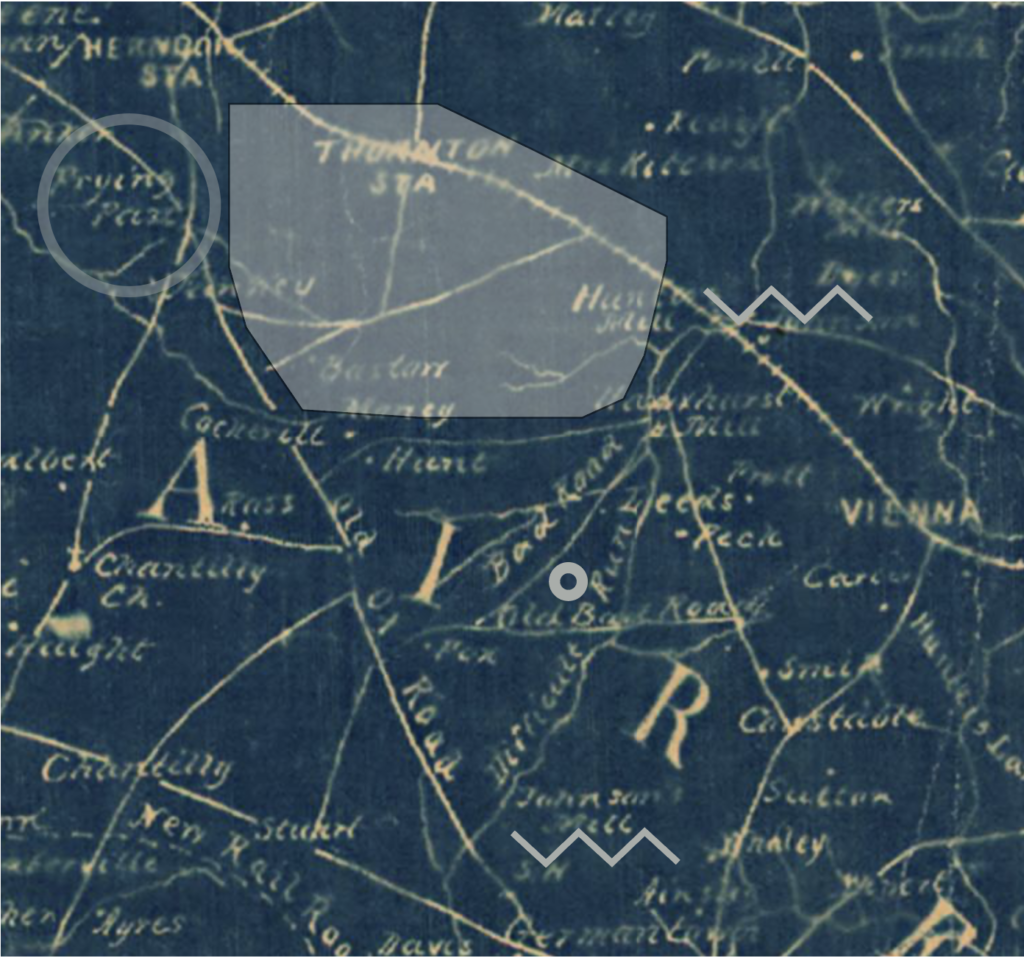

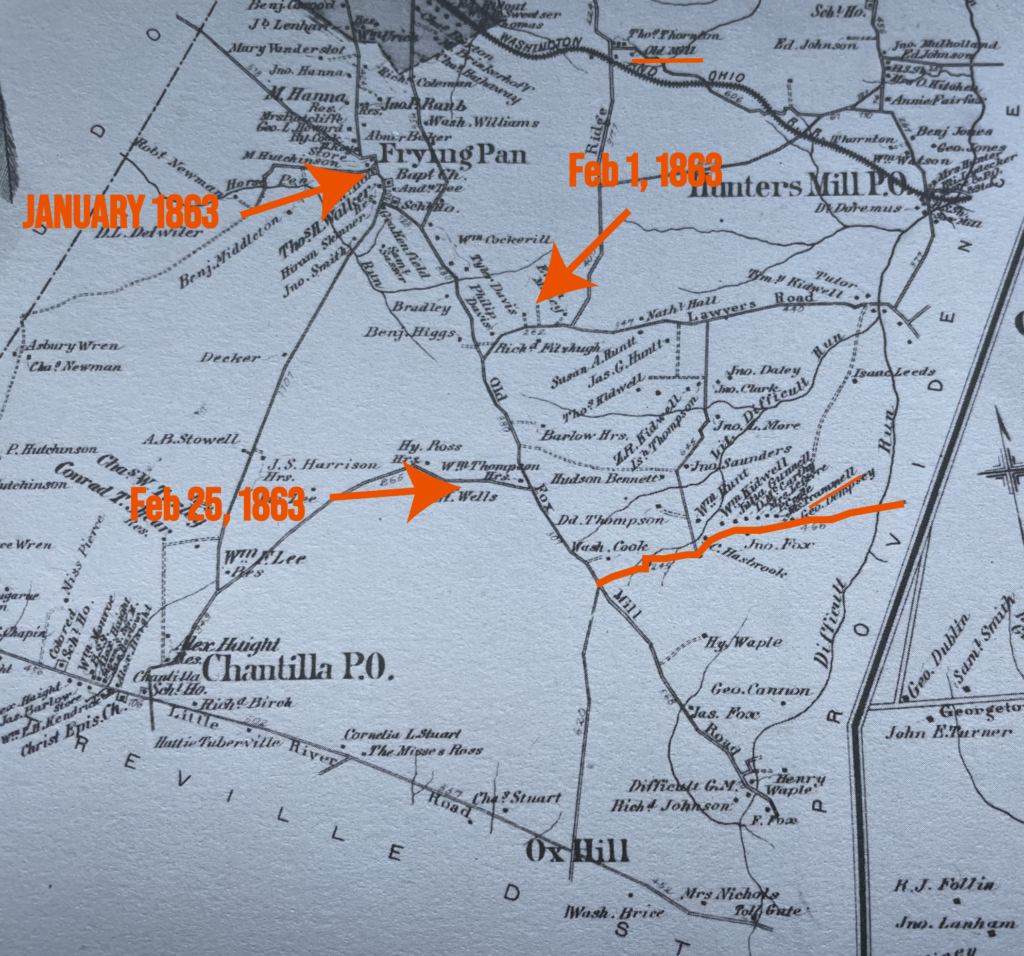

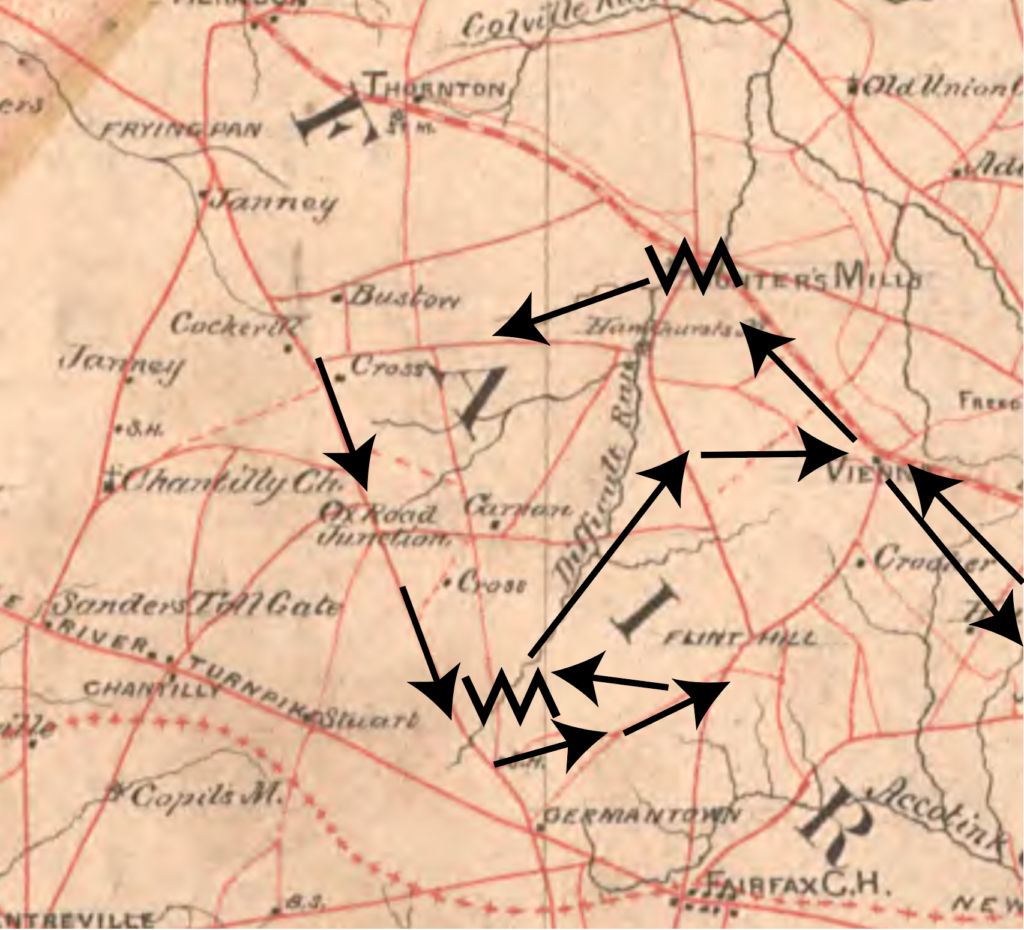

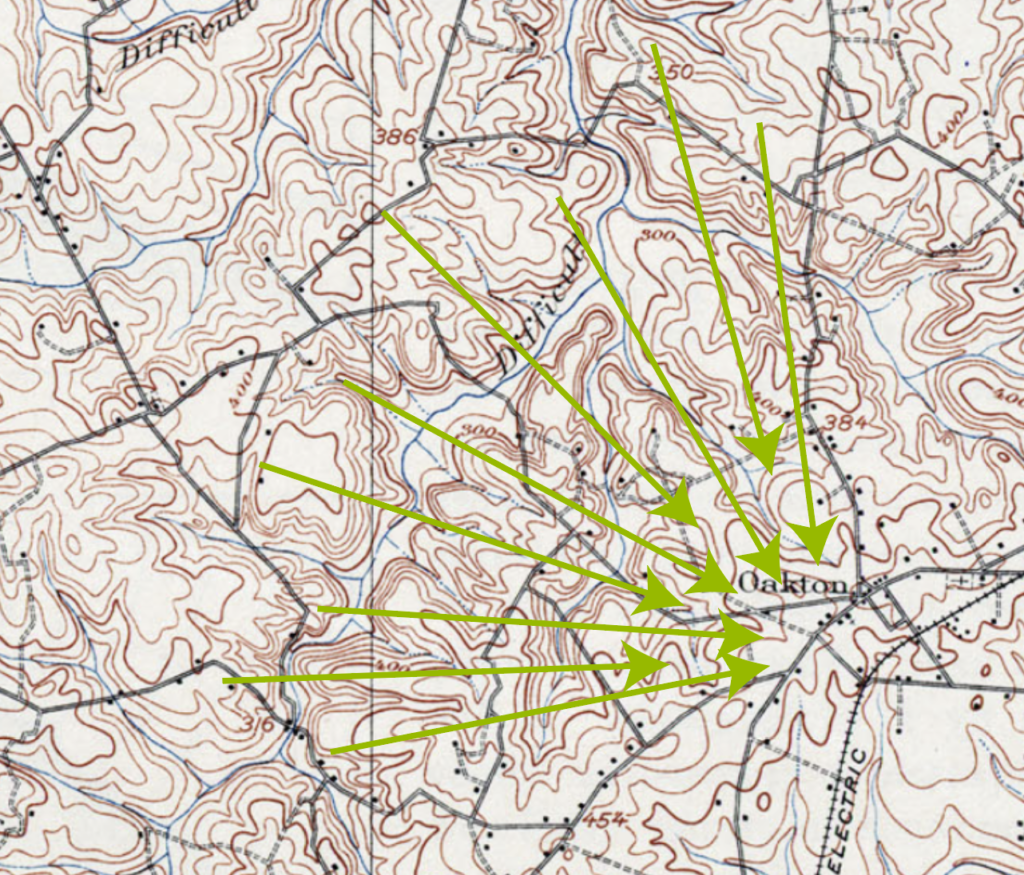

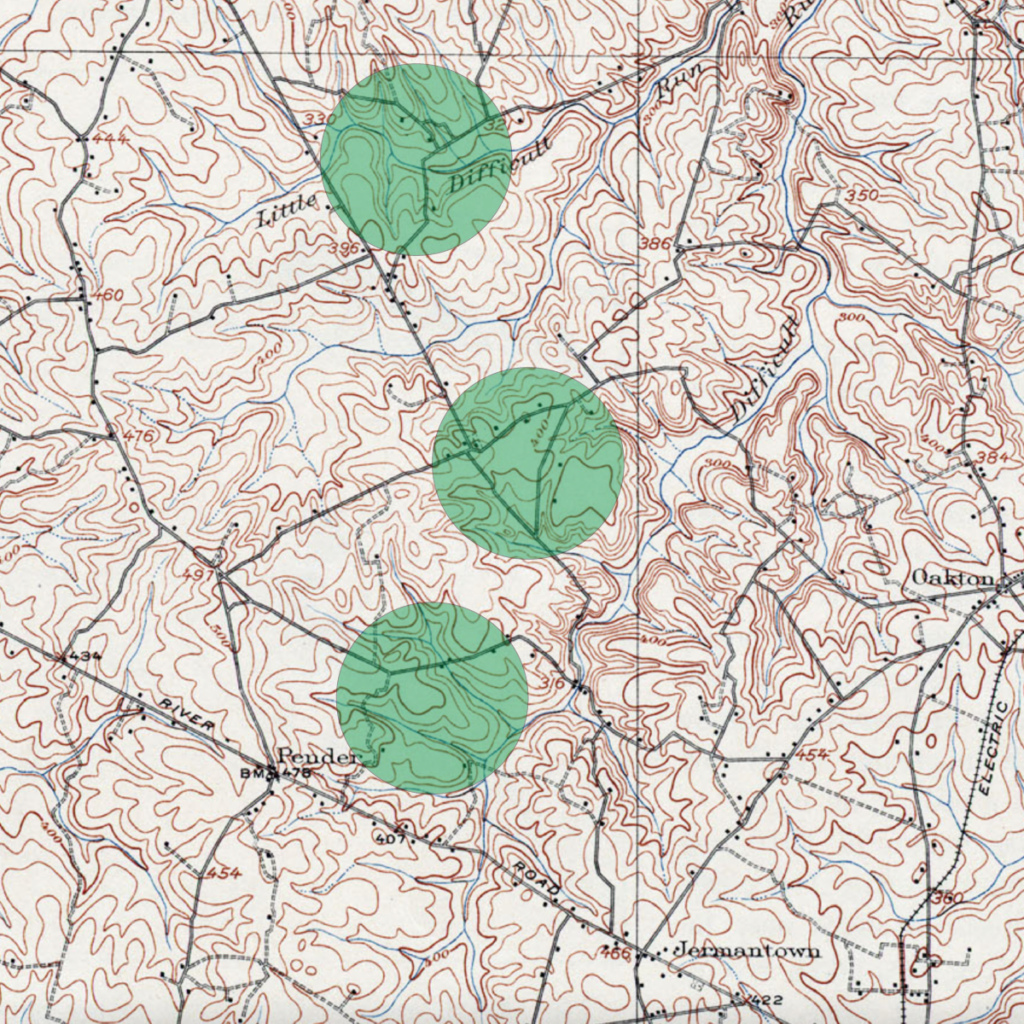

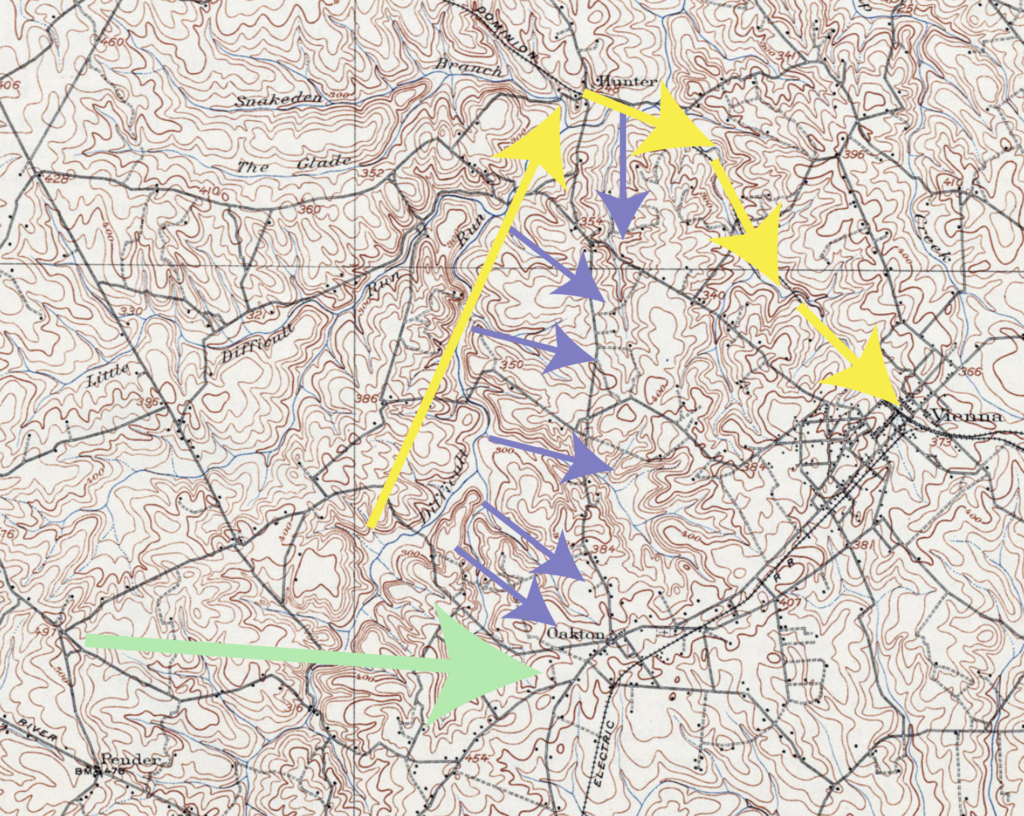

A critical interval is necessarily specific: between February 22 and October 22, 1863, John Mosby and the earliest iterations of his Rangers utilized a corridor of friendly farms hidden behind hills and thicket in a 4.4 mile span of Difficult Run jacketed by Fox’s Lower Mill to the south and Hunter’s Mill to the north.

The cult of Mosby is steeped in broad stroked assurances that can feel short on specifics at times. It’s important to rigorously defend the dimensions of the critical interval. In this case, a short and poetic passage about shadowy horsemen darting forth from unknown forests in the dead of night will not suffice.

Out of the Fire and Into the Frying Pan

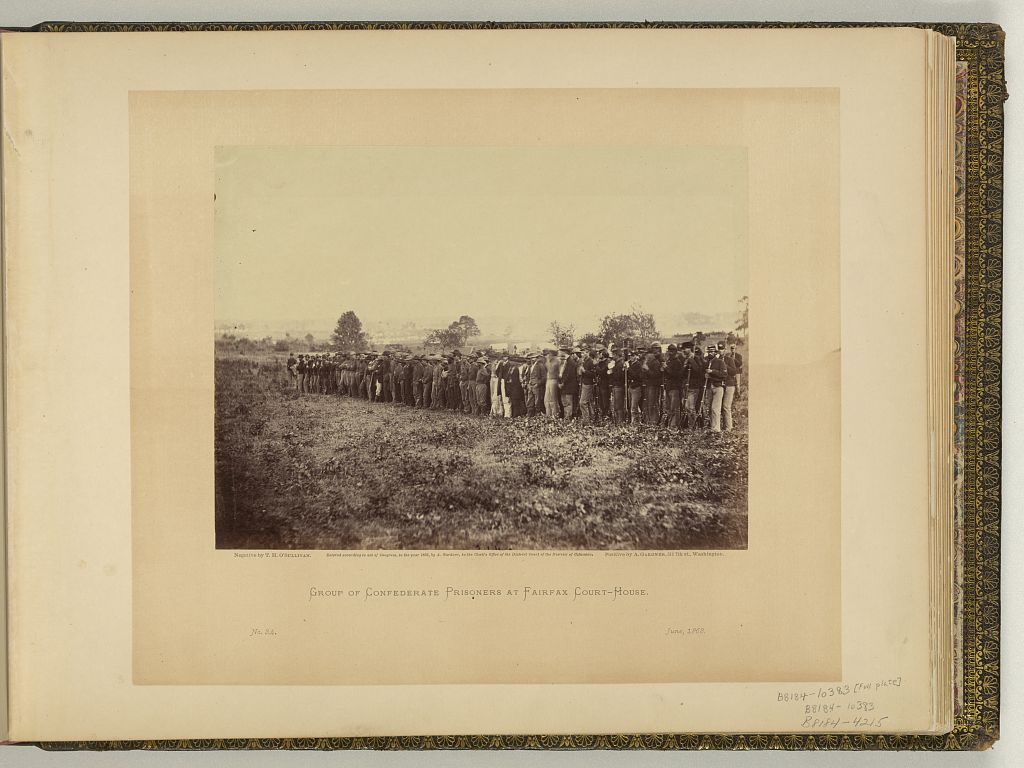

January 5, 1863 is a perfect moment to begin shelling the core of John Mosby’s wartime efforts in Fairfax County from the lore of “Mosby.” On this day, Mosby’s command—sanctioned and ordered by JEB Stuart—made its first foray into Fairfax County.

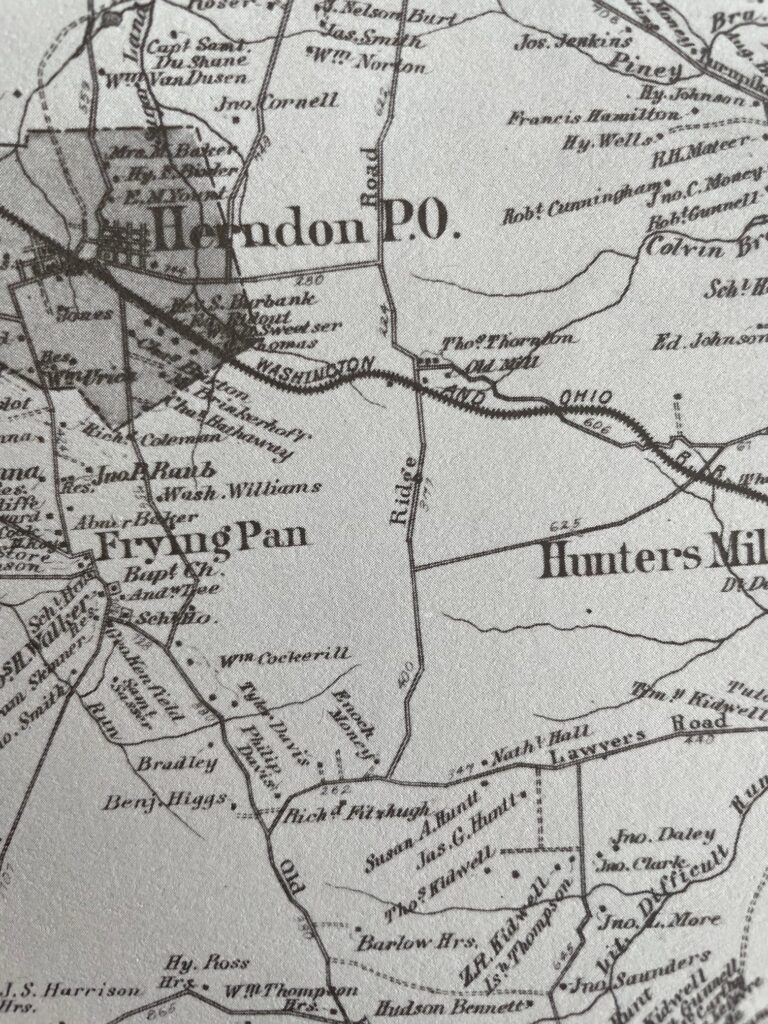

Reverend Louis Boudrye, historian of the 5th New York Cavalry regiment which was then picketing the Federal outpost line between Herndon and Centreville, recorded the loss of thirteen men captured near Frying Pan and Cub Run.4

Soon thereafter, Mosby recrossed the Rappahannock and reported to Stuart. With fifteen picked men, Mosby darted northwards again on January 18 (erroneously recorded in his own memoirs as January 24).

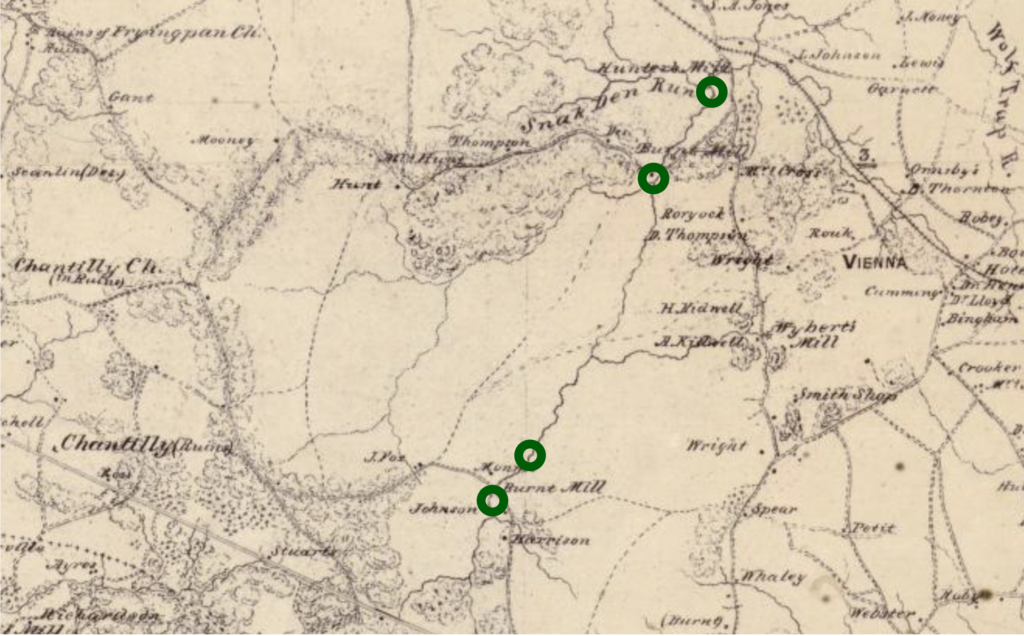

For the next month, Mosby made forays to the vicinity of Frying Pan Church and Chantilly. This is the first chapter in the story of his independent command and an important preface to the story of John Mosby in and around Difficult Run.

With successive attacks on January 26 at Chantilly and January 31/February 1 and again on February 7 at Frying Pan, Mosby began to formulate a doctrinal pattern. His obsession with Frying Pan as a first point of assault is telling.

At Frying Pan, the axis of Federal cavalry patrols (then slicing north/south along the Centreville Road between Herndon and its titular terminus) was intersected by bramble thickets and timber that hid the irregular course of Horsepen Run.

The stream was a point of integration where the broad, flat Culpeper Basin scrunched up against the crystalline ridges that divide the sprawling plains from the sunken Difficult Run basin just to the east. Here sixteen men unbeholden to roads could follow the hidden course of the creek on a direct path past and through Federal lines.

At the earliest moment of his command, John Mosby discovered great success at a point where advantageous and unpicketed water courses could be used as unorthodox roads.

So too, Mosby gravitated to the vicinity of Frying Pan on Horsepen Run because of a prior association with friendly locals. To wit: Laura Ratcliffe. A dyed-in-the-wool Southern sympathizer and a principal figure in one of the lovey-dovey, extra-marital friendships that dotted JEB Stuart’s life, Ratcliffe was a reliable source of timely intelligence for Mosby throughout his guerrilla career.

By January 1863, Mosby has a pre-existing relationship with Ratcliffe. In fact, she and her first cousin Antonia Ford (later arrested under suspicion of providing Mosby with intelligence herself) were possibly the impetus for Mosby’s first jaunt through Difficult Run when in the winter of 1861-62 Stuart tasked then Private Mosby with accompanying two women on a snowy journey from Fairfax Court House to a house “near Frying Pan.”56

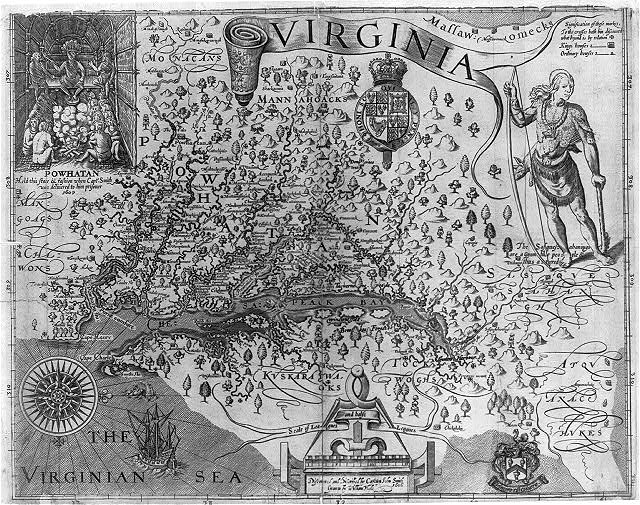

As maps of the era reflect, the path between Frying Pan and Fairfax was best served by a conglomeration of roads following the path of today’s Waples Mill Road to West Ox Road. Mosby could have taken the cousins on the longer route, but by 1862, a pocket of infrastructurally devoted Baptists living on Difficult Run at Fox’s Mill had ensured a reliable route from Jermantown directly to the Baptist Meeting House at Frying Pan.7 So prominent was the road that Federal maps mistook it for the “Old Ox Road.”8

When Mosby gravitated towards Ratcliffe in January of 1863, he invoked a prior relationship and a potential source of intelligence. Seen in another way, he was building a valuable doctrinal cornerstone by absorbing someone’s specific place knowledge into the operational capability of his command.

This pattern repeats itself frequently in the Mosby story. Rangers were recruited not just for their handiness with horse and pistol, but for their ability to provide privileged place knowledge.

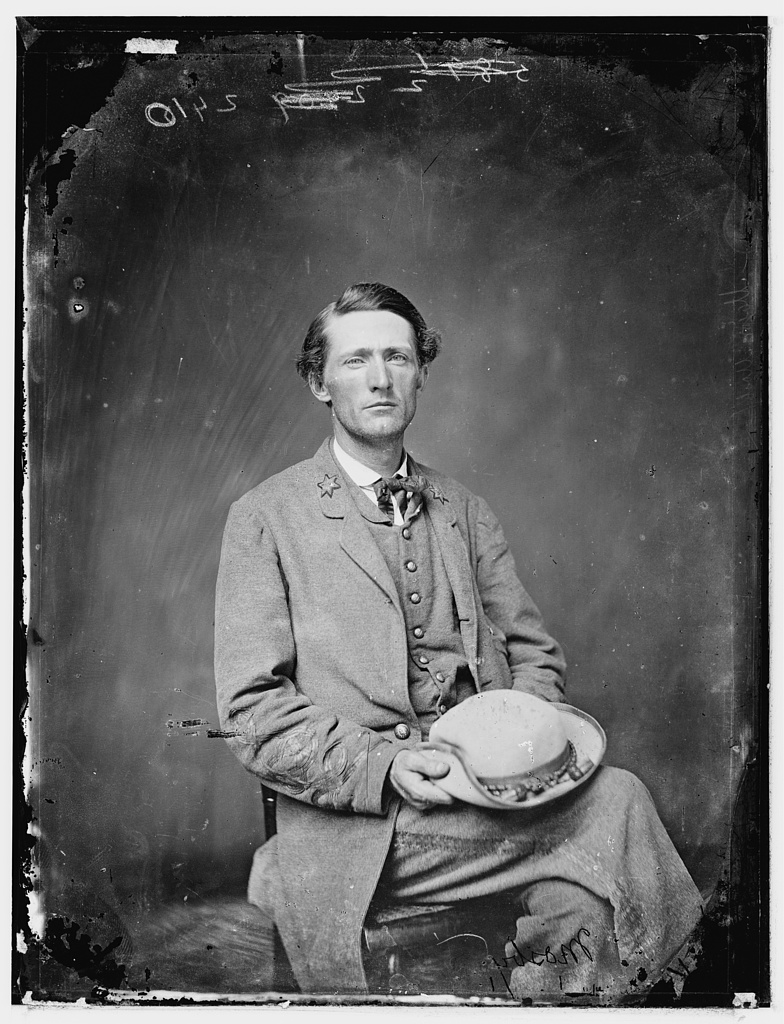

Underwood, Literally

Nowhere is this more apparent than the discovery and enlistment of John Underwood in early January of 1863. Described as “a resident of Frying Pan,” Underwood was—true to his name—a woodsman engaged in the timber industry.9 Virgil Carrington Jones said of Underwood that he “knew paths not even rabbits had found.”10

Mosby is said to have literally happened on Underwood in a thicket one day. A keen and immediate contributor to Mosby’s agenda, Underwood led Mosby into his very first engagements along Horsepen Run at Frying Pan.11

John Underwood was no one trick pony. The place knowledge he brought and integrated into the Mosby command was sprawling and priceless. As fellow Ranger John Munson would say of the company’s first and most prominent scout and his brother, Bushrod, “These Underwoods knew that country better than the wild animals that roamed over it by night or by day, and they were Mosby’s guides on many of his scouts and raids and never led him astray. By night or by day any of these boys could thread his way through any swamp or tangled forest in Fairfax County, and personal fear was a thing unknown to them.”12

Though a resident of Frying Pan, Underwood’s profession made him intimately acquainted with the belt of heavy timber that stretched along the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad on a line eastwards through Hunter’s Mill and Vienna—prime locations along Difficult Run where Mosby and his men would eventually lurk.13

Underwood’s local knowledge extended beyond the professional into the personal. Shortly before the war, John Underwood married Margaret Trammell.14 His second wife, Margaret was part of a broad kinship network that once handled much of the milling along Difficult Run.15 Sons of the Trammell family and interwoven Gunnell families would eventually form important aspects of Mosby’s command. It’s worth noting that in 1860, much of the land still owned by the Trammells sat along Hunter Mill Road. Some of these parcels were located just above Difficult Run along Old Bad Road.16

In a very real sense, Mosby was able to gain a foothold at Frying Pan and begin projecting into Difficult Run because of the illuminating influence of John Underwood’s unique spatial history. On April 19, 1863, Underwood and fellow ranger Walter Franklin captured Lieutenant Robert Wallace of the 5th Michigan Cavalry while scouting the woods near Hawxhurst’s Mill (just west of Hunter’s Mill Road on Lawyers).17 In June, Mosby tasked Underwood with initiating an ambush intended to draw federal forces into a larger bushwhack somewhere north of Fox’s Mill. Underwood chose a position along Lawyer’s Road where he could slip away in familiar thickets that were prohibitively dense and unnavigable to his pursuers.18

Both of these vignettes occur in the critical interval, but say more about Underwood than Mosby. Each is a superlative individual effort play executed by a skilled and brave woodsman who returned to his old professional stomping grounds and the haunts of his in-laws to do his dirt.

More telling than John Underwood’s ability to scout and snipe alone in Difficult Run is the centripetal influence he exerted on Mosby’s command at large. The area access and path knowledge he brought to the table enabled Mosby to traverse the upper reaches of Horsepen Run. Here, Federal cavalrymen were strung out in a loose array of pickets and patrols on prominent North/South ridge roads perched above the timber tracts in Upper Difficult Run.

With clear access and superior bridle-path intelligence, Mosby and his men began to undermine the Yankee position guarding Difficult Run. On February 1, the Gray Ghost and his men compelled the assistance of a neutral local, Ben Hatton, to thread through a Union ambush and stab at a picket post near the Tyler Davis house in the vicinity of today’s Fox Mill Shopping Center on Reston Parkway.19

On February 25, 1863, the command dominated a 50-man Federal picket relief post at the Thompson Farm. Located just under a mile north of Ox Junction where the road to Fox’s Mill, Old Bad Road, and the Ox Road intersected on the heights above Difficult Run, the Thompson’s Corner raid was a dominant victory for Mosby and an important milestone for his command.20

February 25 marked the opening of the critical interval. Bruised by two months of blind dust-ups against a determined and apparently informed rebel force, Federal cavalry commanders were beginning to waver in their defense of the phase line just to the west of Difficult Run. By early March, the Federal line protecting Frying Pan on the Herndon/Centreville road was found to be porous and poorly maintained.21 Requests to vacate the posts west of Difficult Run were beginning to circulate amongst the Federal command. Though not approved until late March, these documents speak to demoralization and disorganization that essentially unlocked the roads into Difficult Run for John Mosby.22

At this critical date, Mosby achieved a path of ingress from the Culpeper Basin, up Horsepen Run, and down Ox Road to a position overlooking both the Little River Turnpike and the Difficult Run/Lawyers Road/Old Bad Road axis. More importantly, secessionist-inclined men in these neighborhoods were beginning to flock to the successful guerrilla and offer up place knowledge that interlocked with that provided by John Underwood.

Enter James Ames and Jack Barnes.

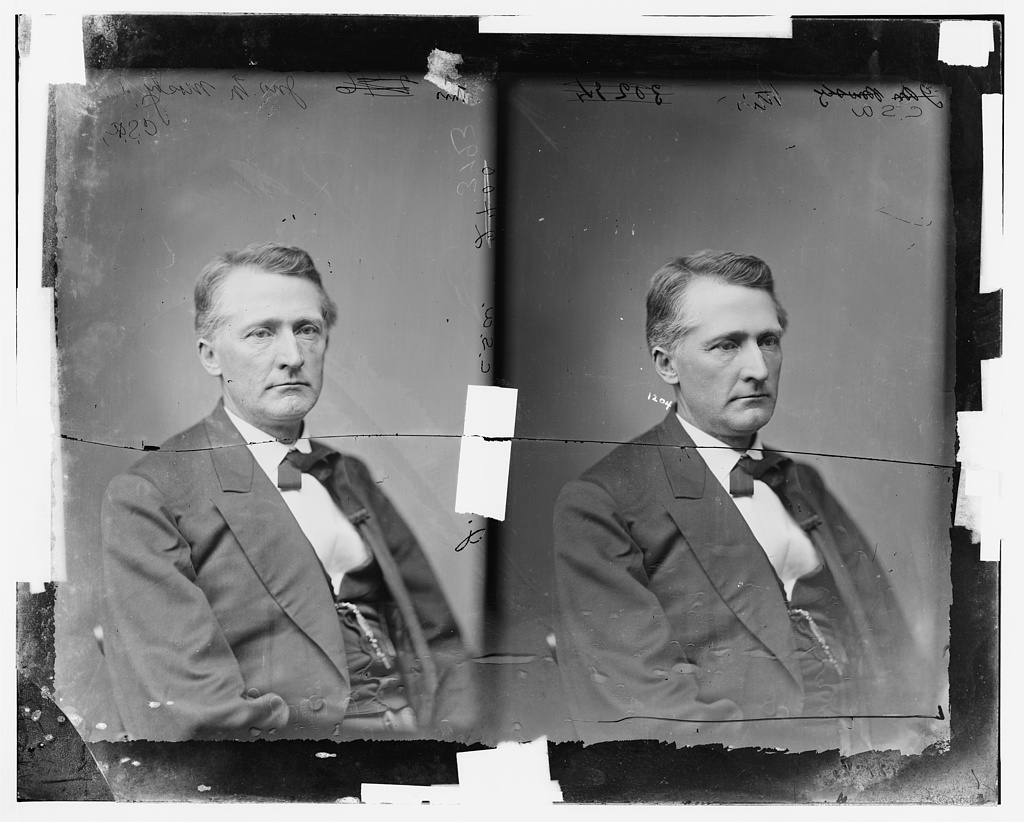

Big Yankee

One of the most compelling features of John Mosby’s early-1863 intelligence profile is the place information gleaned from “Big Yankee” Jim Ames.

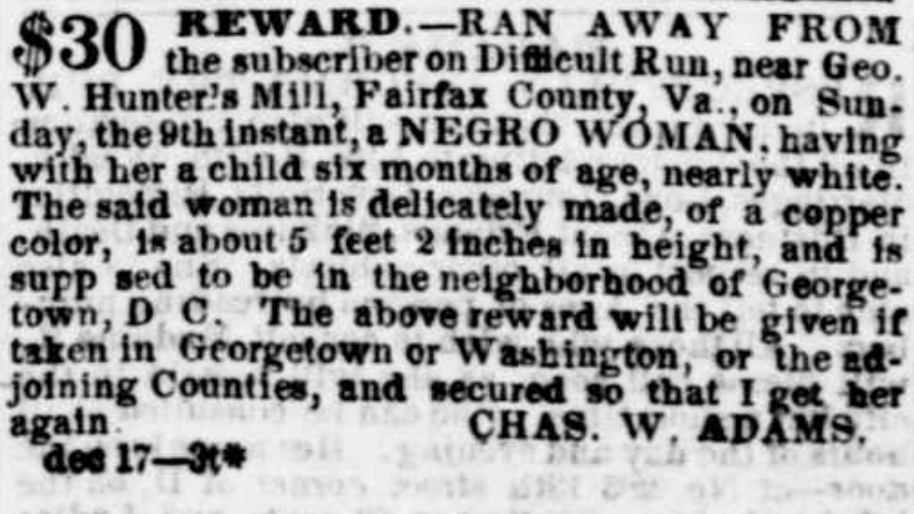

Multiple historical accounts agree that Ames was a substantially-proportioned man hailing from Bangor, Maine. He enlisted in the 5th New York Cavalry, which brought him to Jermantown. Ascending to the rank of Sergeant, Ames took leave of his blue-coated colleagues on February 10, 1863. Horseless and unarmed, the massive Yankee sauntered into Rector’s Crossroads twenty eight miles west of his post the following morning, much to the surprise of Mosby and his men.23

`Ames’ desertion from the Union Army and zealous conversion to Confederate service has never been satisfactorily explained. “Big Yankee” was involved in an unfortunate friendly fire incident on a dark road near Piedmont, Virginia in 1864 that laid the Galvanized Rebel in his grave, removing any possibility that he could clear ambiguities regarding his origin story.24

In his Memoirs, Mosby offered of Ames’ motivations, “I never cared to inquire what his grievance was.”25 Others were apparently less tactful.

Virgil Carrington Jones presented a story that Ames’ was inspired to switch sides primarily out of disgust for the Emancipation Proclamation. “The war had become a war for the Negro instead of a war to save the Union,” offered Jones in uncited quotes.26

Whatever the impetus, Sgt. Ames brought a wealth of knowledge about Federal dispositions and protocol to Mosby’s camp. Specifically, Ames was intimately familiar with the vicinity of Jermantown.

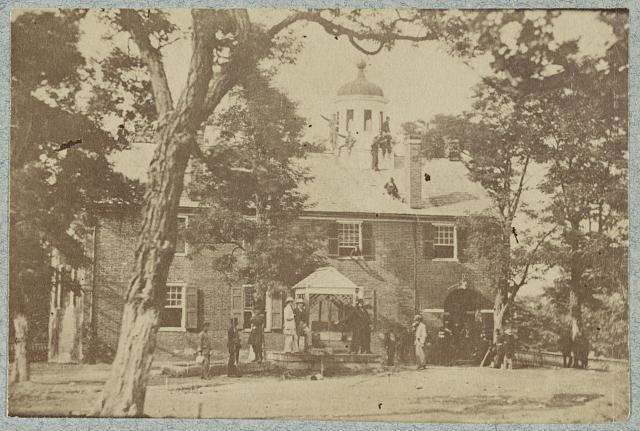

Frequently stylized as “Germantown” by wartime sources of both sides, Jermantown’s name paid homage to the Jerman family farm once located near today’s H-Mart. The town-sized neighborhood of Fairfax Court House sprouted on a commanding ridge one and a half miles west of the court house proper.

Before the war, Jermantown was a hodgepodge of independent small farmers, merchants, and mechanics.27 The latter trade is especially important. Jermantown hosted the confluence of two major regional roads—the Warrenton and Little River Turnpikes—and was the wartime conduit for the Ox Road running through Difficult Run to Frying Pan, Herndon, and the Leesburg Pike beyond.

Jermantown was a prominent tactical objective of Stonewall Jackson on the last day of August 1862 in the lead up to the Battle of Chantilly. During the Battle of Ox Hill on the following day, John Buford’s federal cavalry used the intersection a headquarters.28

Properly occupied, this fortified ridge jacketed a critical intersection and shielded Fairfax from marauders. More importantly, it was an essential staging area for the projection of power into Difficult Run. The western-most limits of Jermantown peek out into the watershed, control the roads along its headwaters, and overlook the swampy valley near Fox’s Mills—only a mile north.

Jim Ames offered a key to unlocking this corner of the Difficult Run Basin. Mosby later wrote of his first encounter with the Yankee deserter, “The account he gave me of the distribution of troops and the gaps in the picket lines coincided with what I knew and tended to prepossess me in his favor.”29

Still, Ames’ tenuous position as a potential double agent inspired a want of confidence from Mosby’s Men. The newcomer was forced to earn their trust by ordeal.

On February 28, 1863, Big Yankee Ames and Walter Franklin, a recently dismounted member of Mosby’s command, set out on foot per Mosby’s explicit instruction to steal horses from the Federal camp at Jermantown.30

The near-thirty mile trek from Rector’s Crossroads took multiple days and necessarily involved the negotiation of Federal picket posts in the Difficult Run Basin. Eventually, Ames and Franklin found themselves in a stand of pine near today’s Katherine Jackson Middle School, where the two went unchallenged as they stole prime Yankee horses for Confederate operations.31

Ames’ knowledge and faith in Ames guilded together into a powerful resource for unlocking the interface where the Difficult Run bottoms intersected with the otherwise strong Federal position at Jermantown.

Within ten days of Ames’ jaunt through enemy lines into Jermantown, his worth as a place scout was proved conclusively with the success of Mosby’s most daring and enduring act—the Fairfax Raid of March 9, 1863.

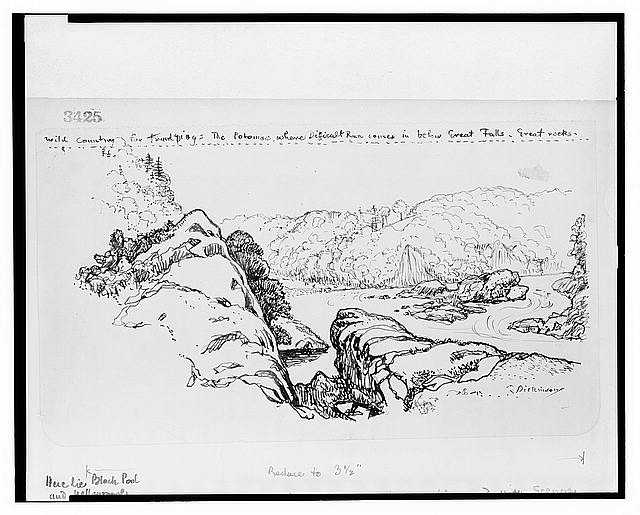

It was an audacious operation. Mosby and a few dozen men struck out along the Little River Turnpike before slicing south to an unguarded avenue between Centreville and Chantilly where the command proceeded undetected toward and across the Difficult Run Basin.32

Mosby and company entered the village of Fairfax Court House from the south and began to pick their way through the town’s finer houses that quartered high-ranking Federal officers. The target of their raid—Ames’ once and former commanding officer, Sir Percy Wyndham—was nowhere to be found. Instead, a handful of prominent Yankees, including Brigadier General Edwin Stoughton, and a few score horses were snatched from their respective beds and stables and brought back to Confederate lines.

The success of the raid owed a significant debt to the place knowledge of Big Yankee Ames. Still, it was a group effort. One that quietly and immensely benefited from the presence of John Barnes.

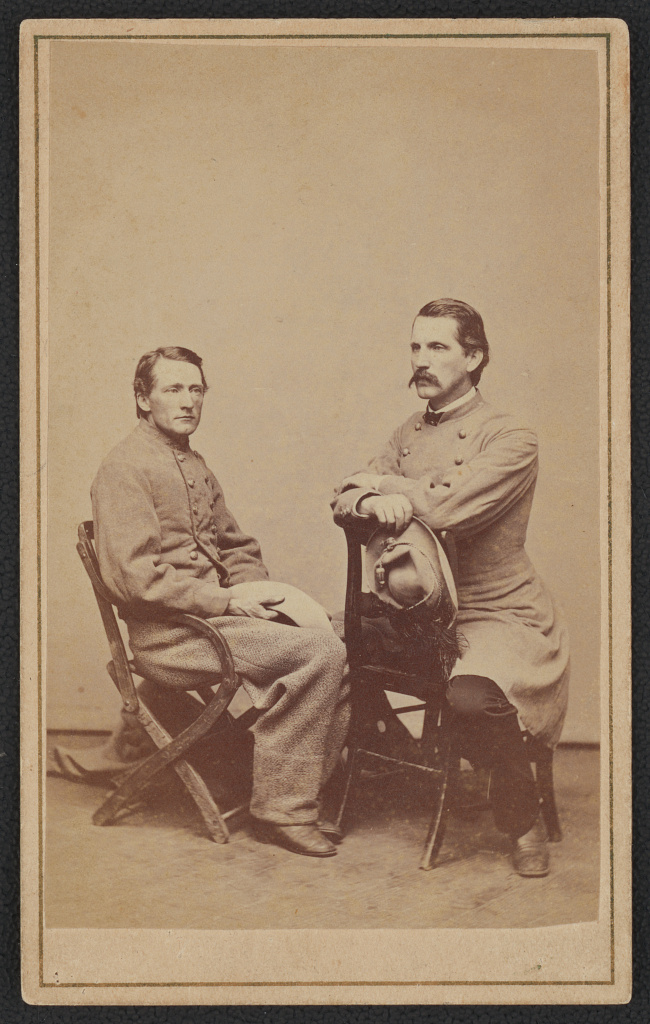

Jack Barnes

It is an interesting testament to Mosby’s litigious mind and sense of discretion that the men who he credited most for their valor and significance died during the war. Though never confirmed, it’s reasonable to believe that precedence was given to the dead as an honorific and a hedge against post-war retribution. Men of Difficult Run who performed valuable service in negotiating Federal lines that survived the conflict were rarely given the same weight as pillars of Mosby lore like John Underwood and Big Yankee Ames who died during the war.

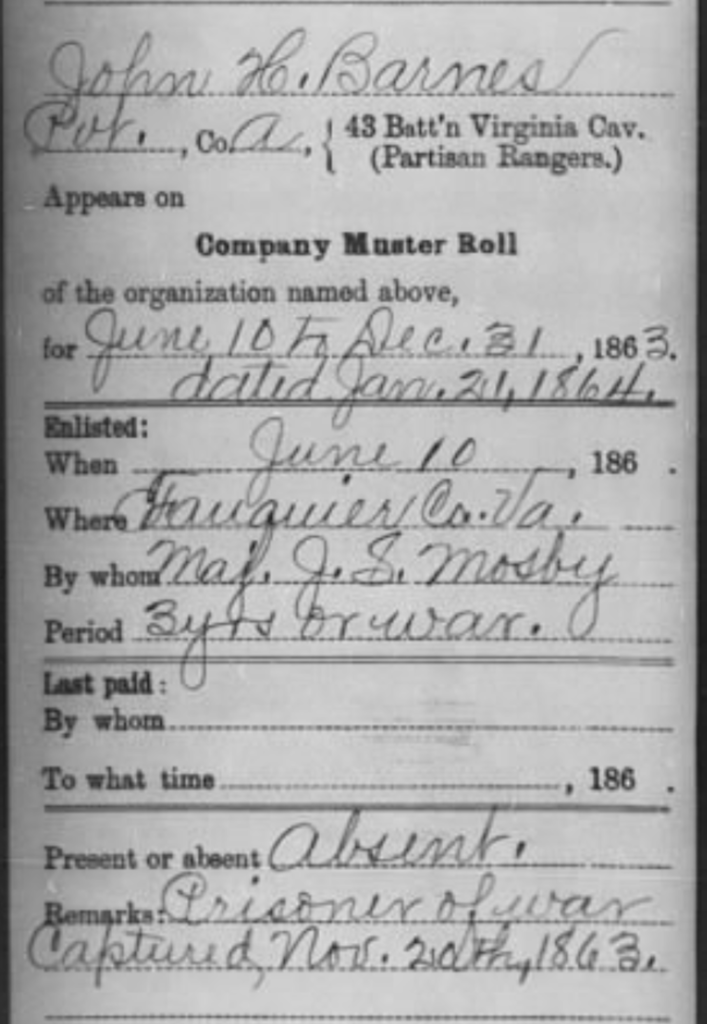

John Barnes survived to be barely a footnote.

Upon further examination, Barnes was an early and important instrument in the facilitation of Mosby’s dominance of Fairfax County. In a very real sense, Barnes’ marginalization in the story of the Mosby organization mirrors the neglect that has been shown to Difficult Run as an area of operations.

John Barnes accompanied Mosby on the Fairfax Raid and suffered for it a week later when he was arrested on rightful and potentially correct suspicion of having guided Mosby and his men into the village. We know that Ames and Frankland were prominent in this process, but Federal authorities immediately targeted John Barnes—a paroled Confederate soldier whose family was concentrated at Hope Park, just south and west of Fairfax along the route Mosby used for ingress and egress.33

Barnes was indeed a known quantity in this stretch of Fairfax County. In 1853, he inherited the Piney Branch Mill near Popes Head Run.34 This thread of professional association was potentially enough to knit one milling family into another. In the early-1850s, Barnes married Mary Isabella Fox, the eldest daughter of Gabriel Fox, the deceased owner of the Fox Mill complex that dominated Upper Difficult Run.

So it is that Barnes came into part ownership of Squirrel Hill. Today, this piece of remarkably resilient mid-18th century vernacular architecture has been integrated into a larger modern home on Lyrac Court in Oakton, Virginia. In the pre-war landscape of Difficult Run, Squirrel Hill was a prominent landmark.

Millers occupied unique roles in localized micro-economies of pre-industrial America. The Fox family of Difficult Run was no exception. They not only processed raw materials for distribution to wholesalers, but they themselves likely purchased raw grain and timber before it had been processed. They were necessarily of means and importance.

When he died in 1844, Gabriel Fox was described as enterprising and industrious, but also charitable. “Instead of speculating on the necessities of the people,” read his obituary, “he would forego an extra profit to supply the poor with bread.”35

This focal existence radiated outwards from a constellation of mills that integrated with Squirrel Hill—the Fox family home. War-era maps show trails arcing up from the Ox Road through modern Willow Glen Court to the homesite off of Old Bad Road with similar routes carving their way to the lower mill on a path that traversed old native sites, crossed Difficult Run, and intersected with the Ox Road near Jermantown.

Rich in ad hoc road connectivity, but reasonably distant from major thoroughfares, it’s no wonder that family lore connected to Squirrel Hill identifies the place as having served as a headquarters for John Mosby at some point during the war.36

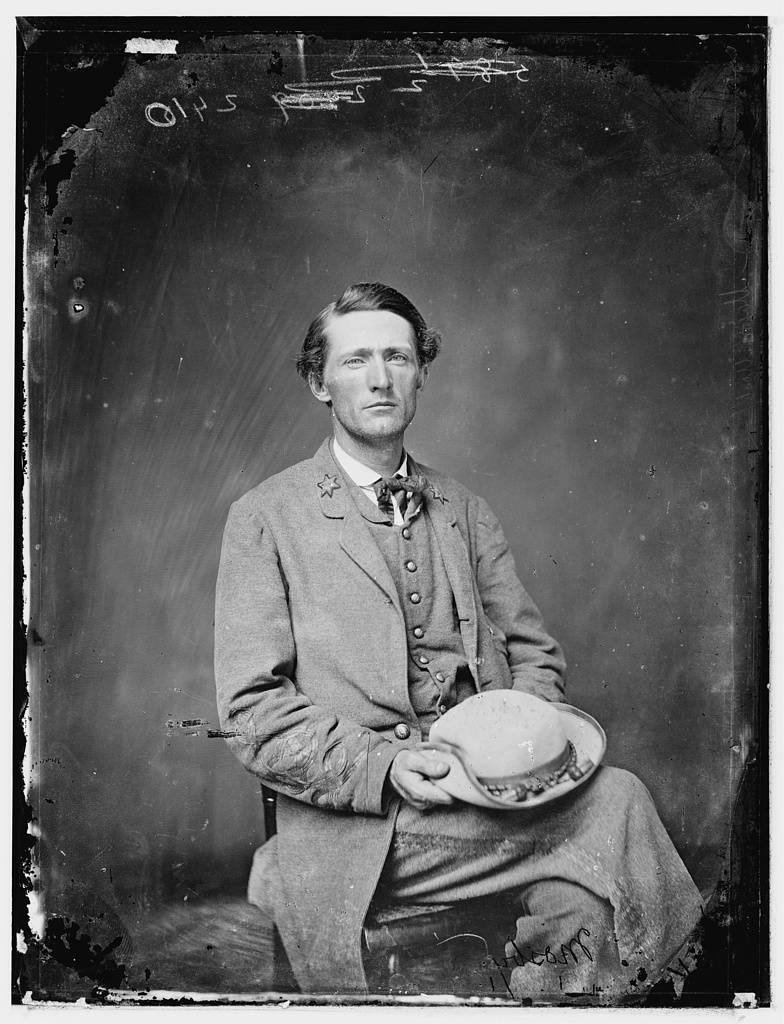

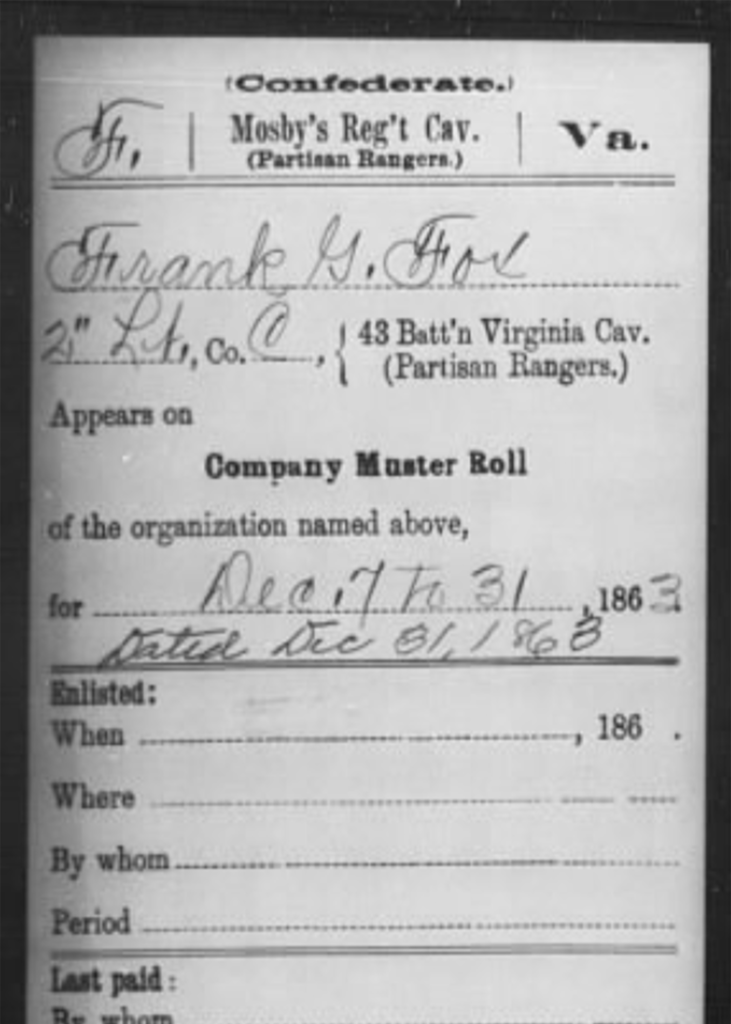

Jack Barnes, his wife Mary, and his brother-in-law, fellow ranger Frank Fox, sold the home in 1855, but the place knowledge likely never evaporated.37

After the war and potentially before, Barnes kept a small house near 11321 Waples Mill Road.38 The critical hint here is that Barnes joined the Mosby command at exactly the moment when the Confederates began to push south on the Ox Road (modern West Ox Road) toward Little River Turnpike. If Barnes were at Hope Park south of Fairfax, he would not necessarily have been privy to Mosby’s operations. However, Barnes was in Mosby’s ranks in time for the Fairfax raid and just after the fight at Thompson’s Road.39 This signals that he was living somewhere in and around Ox Junction at the time and would have been available to flesh out knowledge of Old Bad Road. In this way, Barnes was very likely the holder of connective place knowledge that united the spheres of Big Yankee Ames and John Underwood.

Friends and Family

Geography aside, John Barnes knit the social fabric of Difficult Run with the fate of John Mosby at a critical juncture. In the immediate aftermath of Mosby’s Fairfax Raid, Federal authorities cast a broad net for potential Confederate sympathizers in a wave of arrests.40 The neighborhood of Fox’s Mills on Upper Difficult Run was targeted with special zeal.

Barnes, who was captured on March 13, found himself incarcerated with his brother-in-law Frank Fox, his step-father-in-law, Richard Johnson, their young neighbor Philip Lee, and another erstwhile neighbor, Albert Wrenn.41

Paroled (again) on March 30, Barnes rejoined Mosby near Upperville. Upon his release in April, Frank Fox rendezvoused with his brother-in-law, Barnes, and added his name to Mosby’s rolls. Fellow captives Phillip Lee and Albert Wrenn joined that day as well. By July, Frank’s younger brother, Charles Albert, had enlisted. Minor Thompson, a near neighbor who had avoided the Federal sweeps, beat them to the punch by offering his services to John Mosby on the last day of March.42

It is reasonable to propose that a cocktail of Mosby’s stunning successes against Federal cavalry, punitive Yankee arrests, and the example of John Barnes secured the support of the available young men in the Upper Difficult Run Basin.

Though no other Yankees are reported to have followed Jim Ames to the Rebel side, the influence of both Barnes and John Underwood pulled Mosby deeper into Difficult Run and drew more and more local boys to Mosby’s ranks.

Through the summer and fall of 1863, a trio of friends—Thomas I. Clarke, John Saunders, and James N. Gunnell—who lived near the intersection of modern Fox Mill and Stuart Mill Roads all made the pilgrimage west to join Mosby.43 James Gunnell’s brother, George West Gunnell, offered his services as well.44 The son of the Fox Mill school headmaster, Thomas Lee, joined his elder in service and three men of the Trammell family who were related to John Underwood by marriage joined him in Mosby’s fold.45

These “friendly locals” who had grown up utilizing main roads and ad hoc desire paths lacing through the Difficult Run Basin were the fuel for a brief golden period of operations in the area between Ox Junction and Hunter’s Mill.

Mosby Country

On March 18, Mosby observed the proposed contraction of Federal lines that walked the footprint of established Yankee pickets east of Difficult Run. They simply could not maintain the furtive posts on the Centreville and Ox Roads that Mosby had picked apart.46

For over a month, Mosby was free to operate with near impunity in the area. This time frame coincides with bold actions taken on the part of John Underwood on the Lawyers Road corridor.47

In April, the local Federal cavalry commander, Julius Stahel, was instructed to cooperate with the Army of the Potomac’s proposed thrust over the Rappahannock. Mosby’s familiar adversaries were pulled from the Federal lines in Difficult Run and replaced by two regiments of infantry, the 111th and 125th New York. Under General Abercrombie, these foot soldiers held the Ox Road between Jermantown and Frying Pan.48

Tasked with guarding the ridge line which Mosby had used to access the Difficult Run Basin from the vicinity of Horsepen Run, these Federal infantrymen experienced a number of scares as small penetrations by Confederate guerrillas became routine.

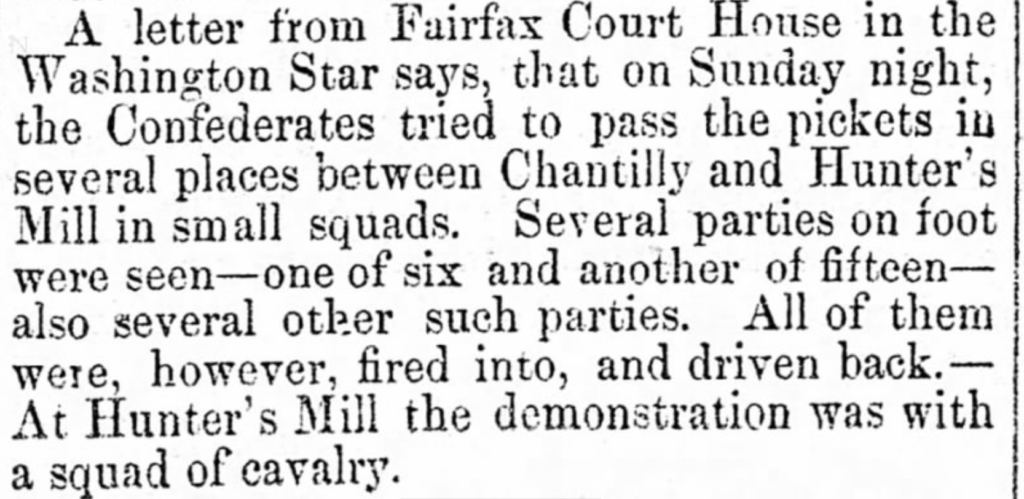

As the Alexandria Gazette reported on April 14, “Confederates tried to pass the pickets in several places between Chantilly and Hunter’s Mill in small squads. Several parties on foot were seen—one of six and another of fifteen—also several other such parties. All of them were, however, fired into, and driven back.—At Hunter’s Mill the demonstration was with a squad of cavalry.”49

Confederate partisans under John Mosby had already established the route into Difficult Run as a prime corridor for their operations.

In the last week of May and first week of June, Mosby began targeting large scale patrols on both Lawyers Road and the stretch of Ox Road that ran through Fox Mill. These operations are remarkable in both their scale and location. Grappling with and defeating company-sized elements of Federal forces required Mosby to predict his enemy’s arrival and funnel them toward a disadvantageous landform where they could be chewed up.50

Mosby was apparently secure enough in his ability to operate within Difficult Run that he initiated these ambushes. So too, the Federal command took the potency of Mosby’s heightened threats in the area seriously.

By early June, the 6th Michigan was moved from Jermantown on the ridge above Difficult Run to Fox’s Mill itself.51 The position of an element this sized within the watershed itself is an important proof that substantial guerrilla activities were known to be occurring there.

Despite earnest attempts by coordinated Federals who operated in keeping with the best established military practices of the time, the ambushes and assaults continued.

On August 2, reports of rebel cavalry east of Fairfax began percolating. Yankee Brigadier General Rufus King instructed three separate union cavalry patrols to converge on Fairfax Court House. One party from Fairfax Station by way of Burke, another from Chantilly down the Little River Turnpike east, and a third from Fox’s Mill through Jermantown. These parties got word that a party of “30 or 40, with some 20 mules in their possession” had passed by, but the Union interception groups only witnessed two or three guerrillas at a distance.52

Ten days later, Colonel C.R. Lowell, Jr of the Second Massachusetts Cavalry issued a perplexing report that chronicled John Mosby’s movements on a raid toward Annandale, east of Fairfax Courthouse.

“Mosby and White’s men—together about 140 strong—came down Little River Turnpike the day before yesterday, and passed that night near Gum Springs. Moved down yesterday forenoon through Ox Road Junction toward Flint Hill. Hearing that our pickets were there, turned to the north again, and, passing through Vienna by Mills Crossroads, to Little River Pike, near Gooding’s Tavern, captured one sutler’s train there between 3 and 4 p.m. and another about a mile farther east. An hour later, half plundered some of the wagons, took all the horses and mules, and started back in a hurry through Vienna, toward Hunter’s Mill.”53

It is plain from both accounts that the Upper Difficult Run Basin had become something akin to a forward base for John Mosby. Its paths, trails, creek beds, draws, and minor roads had been coopted into interior lines that gave Mosby the ability to disappear at Ox Junction and reappear in Vienna on the other side. Or, alternately, Mosby could dissolve into the woods at Fox’s Mill and cut efficiently cross country to avoid a sizable Federal force moving at high speed toward him from the opposite direction.

Nothing Lasts

The heyday of Mosby as sole inheritor of the Upper Difficult Run began to wane as 1863 continued. Events conspired to thwart the Gray Ghost’s apparent haunting of the area.

The Federal army utilized the ridge roads through and around Difficult Run as a conduit for their march across the Potomac before Gettysburg. Around June 16 and 17th, the Union 12th, 2nd and 6th Corps marched through Hunter’s Mill with the 1st and 5th following a line from Jermantown to Frying Pan.54

In making preparations for the dispositions of the various corps of infantry and artillery that would push through the area, Dan Butterfield, Chief of Staff of the Army of the Potomac, passed to his subordinates the astute observation that “the country in the vicinity of Frying Pan is full of roads.”

He was correct, and, for once, those roads were in Federal possession. Though Mosby himself slipped through massed federal corps arranged around him in a road column during this same time period, it was an inopportune season for a raid—as his boss JEB Stuart discovered.55

Less temporary than a passing formation of infantry, local commanders ordered the construction of a stockade in Flint Hill (modern Oakton) during the Fall of 1863 at the current corner of Chain Bridge Road and Blake Lane.56

Not insurmountable, the stockade and its occupants did present a fresh hindrance to Mosby’s unbridled use of hidden interior lines on Difficult Run.

What was insurmountable was the loss of irreplaceable locals who could navigate this warren of paths. The constant dwindling of Difficult Run men from hard service exacted a toll on Mosby’s ability to operate smoothly in the forests and bottom lands along the creek.

John Underwood was killed late in 1863.57 Big Yankee Ames died a year later, his knowledge of Union positions by then obsolete.58 John Barnes reentered Federal custody on October 22, 1863 during a failed raid against Annandale. Called a “celebrated guerrilla” by his captors, he remained a guest of the Federal penal system until war’s end.59

Barnes’ neighbor and prominent Difficult Run resident, Minor Thompson, was captured on June 12, 1863.60 In June of 1864, the Gunnell brothers were captured at a family home near Gum Springs.61 Then on September 5, 1864, Lieutenant Frank Fox, a capable commander and scion of the Fox milling family, was mortally wounded.62

Albert Wrenn remained in Mosby’s service and brought much of his local familiarity to bear on forward operations in Fairfax County, but the want of good fighters in leadership positions forced Mosby to leverage Wrenn’s services farther and farther westward as a second front against Sheridan opened in the Shenandoah Valley during 1864 and 1865.63

To make matters worse, a deserter from Mosby’s command—Charles Binns—began guiding Federal counter-insurgency patrols through Difficult Run. The enemy had acquired their own privileged place knowledge.64

Mosby continued to utilize the Upper Difficult Run Basin throughout these setbacks. However, the results were never as cleanly executed nor as deeply flummoxing to his blue-clad opponents as they once had been.

On September 15, 1864, for instance, Colonel Henry S. Ganseevoort of the Thirteenth New York Cavalry reported on a lengthy scout against Mosby that began with a night occupation at Fox’s Ford on Difficult Run.

Gansevoort’s group encountered Mosby, but utilized a fresh familiarity with a perviously confusing maze of roads to intercept, aggravate, and ultimately stymie Mosby’s advance.

“On the morning of the 15th of September it (his unit) resumed its march toward Fairfax, all indications and reports of scouts kept on the Centreville Road and roads to left of the turnpike tending to show that Mosby, with a large force, but in divided parties was on the left of the turnpike and between Vienna and Frying Pan. The scouts were driven from Flint Hill, but those at Fairfax reported that Mosby had been seen to pass through the Court-House toward Centreville a short time previous with two men. I dispatched five men to the Centreville Road, about three miles distant, to intercept the party, fearing that more men might fail of an approach. Near Germantown three of this number returned and reported a fight with Mosby, in which two of the men had lost their horses and had taken to the woods, and that large parties of guerrillas were now on the right. On the return of the other men it was definitely ascertained that Mosby, or a person resembling him, had been wounded and had escaped. Mosby had certainly been in vicinity of Fairfax just previous to the action and had gone toward Centreville. People on the road had seen him, and from the description of his person and recognition of his picture by parties engaged, there seems to be some color for the report that he was in the action and was wounded, as he or the person in question was seen before riding off to throw up his hands and give signs of pain. This could be observed, as the action was at very close quarters. I dispatched a squadron to the scene shortly after and moved to Fairfax Court-House, sending a party of thirty dismounted men through Vienna to Lewisville. The regiment reached camp at Falls Church after a march that day of fifteen miles from Chantilly.”65

Despite positional ambiguity, a seasoned Federal force was able in September of 1864 to do what felt impossible sixteen months prior. They identified, tracked, contained, and reversed John Mosby along Difficult Run.

Five months later, a scout in force by Mosby subalterns William Trammell and Bushrod Underwood—themselves seasoned Difficult Run guerrillas—met defeat. Both flanks of Mosby’s forward operating base were no longer as opportunity rich as they had once been.66

Even with these setbacks, the possibility of a Mosby attack was still enough to compel Federal forces to devote immense time and energy to the potential of an advance from this secesh-friendly and very dangerous corner of Fairfax County.

As late as March 7, 1865, a group of gray horsemen surprised a squadron of federal cavalry from a cut near the stockade at Flint Hill.67 Mosby was still a factor until the bitter end.

For simplicity’s sake, it’s important to hone in on the critical months between the raid at Thompson’s Corner on February 25, 1863, and the loss of John Barnes on October 22, 1863. Events as broader than these bookends, but the time between each date encapsulates a rich moment when the bridle paths of Difficult Run were masterfully manipulated in Confederate favor.

A Guerrilla’s Eye For Place

It’s worth taking a moment to consciously depart from traditional patterns of Civil War place memorialization. When we talk about John Mosby and his partisan rangers, we’re dealing with a type of warfare premised on landscape relationships that differed greatly from the locational psychology evident on typical battlefields.

Men who hid and wove their way through lightly-populated, densely-vegetated landscapes to initiate brief and savage pistol fights on a weekly basis enjoy dissimilar memory of place than men who marched for weeks over known roads to array themselves by the thousands on open fields and hillsides that were the subject of medal awards, grand speeches, and lengthy tomes.

To put a fine point on it: we’re not hunting for the place. There’s not going to be a Mosby Marker or a Mosby Trail.

What we’re searching for is an avenue, a constellation of paths, a batch of physical possibilities that account for John Mosby’s ability to disappear between Route 50 and Lawyers Road, West Ox and Hunter Mill Roads and either slink back to Frying Pan and Upperville or project farther eastward into Fairfax County.

There are quite literally thousands of places John Mosby could have been in Fairfax County at one time or another. Chronicling them all would be tedious. Understanding Difficult Run’s role in this geographic drama feels more essential, on the other hand, because of its repeated and obvious use as a staging area for prolonged guerrilla warfare in Fairfax County.

Tracing the routes that enabled John Mosby to bedevil Federal Cavalry until war’s end is akin to shoving bones into the astral body of a ghost. It adds form and structure, something tangible to a thing that is otherwise ethereal. This process also demystifies John Mosby as an apparent wizard. Tying him to specific place patterns establishes links between Mosby’s much-lauded deeds and conventional military wisdom.

John Mosby’s first hero was Francis Marion, the famous Swamp Fox of the Revolutionary War whose biography Mosby claimed was the first book he read for pleasure. In a sense, Mosby entered military service preprogrammed for the cunning use of bottom lands and bad roads.68

The area surrounding Old Bad Road ignited Mosby’s deepest affiliations. Here was a place where Federal maps essentially advised their troops not to go, a place riven with forests and marshlands where a Francis Marion fan could reenact the Revolution.

Another important consideration—perhaps the consideration—is the fact that Mosby’s career as a cavalry scout framed his brain to judge landscapes for their applicability in maneuver warfare. As he did for JEB Stuart on his ride around McClellan’s Army, Mosby looked at infrastructure in Fairfax County with an eye for achieving superior travel time and surprise with massed formations of armed men.69

Mosby’s storied career in Fairfax was received by friend and foe alike as an innovation in warfare. When in reality, he simply redressed Clausewitz, the lodestar military philosopher of the time, on a smaller scale. Slinking through Difficult Run on game paths and kid trails to appear where least expected was a tactic to maximize objective, offensive, mass, economy of force, maneuver, surprise, security, simplicity, and unity of command.

The basin offered force multipliers in all of these respects. Especially noteworthy is the idea that Difficult Run was viewed by most conventional military minds as an obstruction to achieving mass and maneuver. With a force well-served by acute place knowledge and cut down to march cohesively in single file through narrow routes, a thicketed basin such as this became a gold mine of interior lines.

If the name is strange, the principle should be familiar. If a circle encloses an area, it’s easier and quicker for something inside the circle to move to the other side than it is for something outside the circle to trace around the outline and reach the same point.

The classical application in Civil War studies is the Federal fishhook position at Gettysburg, which bent around on itself, allowing George Gordon Meade to rapidly shift forces from one far end of his line to another in order to meet attacks. The Confederates, on the other hand, were stretched on exterior lines that made the translation of men from end to end a time-prohibitive hindrance.

With enough imagination and local support, Upper Difficult Run represented a tremendous opportunity for the use of interior lines. Over a span five and a half miles long as the crow flies, the creek touches or intersects four major thoroughfares that were in steady use by both armies during the war—the Warrenton Pike, the Little River Pike, the Old Ox Road, and Hunter’s Mill Road.

If one knew and controlled the sub-roads therein, a small force could quickly dart between these four roads in a fraction of the time that a pursuing Federal contingent ignorant to those routes could lace their way around to the same point on major roads.

Criteria For A Guerrilla Base

Identifying the bridle paths that served as interior lines for the movement of John Mosby’s guerrillas requires a fine-honed set of criteria. It’s essential to grapple with the existing landscape conditions could have been readily converted to irregular military use in 1863. By balancing what was available and what was useful, we can chart a new map of the Upper Difficult Run Basin.

These five criteria are the basis of that work. Any single one of these factors could have been alluring to Mosby and his men, but the sites where multiple criteria are met deserve particular attention.

- Did the area have desire paths that connected one or more destinations not served by an exiting road or did it offer an alluring shortcut?

- Did this axis follow prehistoric dimensions where paths of least resistance connected local highland forests with marshy bottoms or lithic deposits?

- Did this path cut across Federal lines or achieve some adjacency from which men could quickly breach Yankee-held roads?

- Was the area in friendly possession? Ie: were the people that lived there Confederate sympathizers, families of Mosby men, or absentee yankees?

- Was this route invisible? Was it hidden by some feature of nature or man-made endeavor that made it a less than obvious place to hide?

The logic deserves some explanation.

Desire Paths

The bane of urban planners, desire paths are unforeseen and unsanctioned shortcuts that people choose over formal routes. Think of a foot-worn trail cutting across the corner of an otherwise pristine lawn. Landscapes are strewn with just such paths that connect people and animals with the objects of their desires.

Dan Butterfield’s observation in June of 1863 that the area around Frying Pan was “full of roads” offered unknowing clarity regarding the development of farms and roads in the neighborhood of Upper Difficult Run.70

No courts, ports, markets, or taverns were historically located within the basin. Institutions sat elsewhere, in distant places that each landowner or tenant was incentivized to reach on their own and with the least amount of hassle.

Fifty years after the war, school-aged kids living in Vale—the postwar hamlet that sprouted up on Fox Mill Road near its intersection with Old Bad Road—preferred to thread across fields and forests than take established roads to high school in Oakton.71

Widely-accepted and even encouraged, this practical place negotiation was probably a long-standing tradition in the area. In fact, the roads these students avoided were the very same routes on which Federal forces couldn’t find Mosby and his men fifty years prior. Moreover, the high school they attended was located in the same vicinity as the federal stockade on Chain Bridge Road, which was long a target for Mosby and his men.

The question then isn’t focused on the existence of desire paths in Upper Difficult Run, but charting destinations which would have compelled locals in the pre-war era to beat new paths over hill and dale.

The most obvious candidates for local, informal trail-making were the mill complexes. Beginning around the time of the Revolution, six counties of Northern Virginia were the state’s chief grain producers, accounting for 70% of wheat output.72 This infrastructure magnetized farmers across this region with both economic and social incentives.

Upper Difficult Run was nowhere near as productive a breadbasket as Fauquier County, but nonetheless, huge swaths of the local economy oriented itself to grain markets in Alexandria. From a geographic perspective, these resource flows were unlike tobacco production, in which individual farmers dried and barreled their leaf before rolling it wholesale to ports.

Instead, complex and robust microeconomics developed around local topographic minima where significant drop in creeks and capital investment collided to facilitate the establishment of grain mills.

A successful milling operation like Fox’s Mill or Hunter’s Mill inspired a radial network of informal paths on which timber and raw produce carved deeper traces with each passing harvest. Dragging timber to a milling site will leave a mark.

The explicit economic necessity of these mills represented a fraction of their allure. They were essential gathering spots—places where neighbors could gossip, collect mail, spread news, or simply leave the farm for a few minutes.

It was a phenomenon beyond the boundaries of Difficult Run.

Nan Netherton wrote of the early-1800 mill-boom in Fairfax County, “the water-powered mills often spawned new communities as other merchants began to locate near the mills. New roads were cleared at the end of the eighteenth century in the interior of Fairfax County to provide access to the mills.”73

The community aspect was complex. People forged routes to mills for a variety of reasons. One quiet motivator was stated explicitly in the obituary for second-generation mill owner Gabriel Fox, who died on August 28, 1844. Gabriel’s father, Amos, founded Fox’s Mills on Difficult Run. After his passing, Gabriel consolidated ownership over the mill and developed it into a prime property.

Upon his death, the dimensions of his success became more obvious to posterity. It is clear that Gabriel was no mere miller, but also a speculator and wholesaler who made a small fortune in purchasing raw grain directly from producers before transporting it to Alexandria and cutting his own lucrative deal with flour exporters.

The arrangement put Gabriel Fox and his family in the position of being able to both lend money and render assistance in times of need. As his obituary makes clear, Fox’s Mill was a place where the less fortunate could find relief in hard times.

His obituary in the Alexandria Gazette records that, “He will be much missed by the poorer class of people in his neighborhood.—His course toward them in many points are well worthy of imitation by those having the ability. For instance, in the latter part of the summers when corn was scarce, and the waters low, and persons of property would come to him to engage him to supply them with meal, perhaps offering him an extra price, he would tell them you have means to purchase with, go elsewhere and buy; I cannot more than supply those of my customers who have not the means of procuring from other sources. Thus instead of speculating on the necessities of the people, he would forego an extra profit to supply the poor with bread.”74

If charity wasn’t incentive enough to orient all desire paths towards local mills, strong drink was. The correlation is obvious: mills were sites with an abundance of grain that was underscored by capital liquidity and sharp entrepreneurial instincts. Of course they manufactured alcohol.

In 1816, Amos Fox posted a notice in the Alexandria Herald seeking to either sell outright his prime distillery at Fox’s Mills or hire a good distiller. The still was “within three hundred yards of two mills” and featured “plenty of water running over head” and “mash tubs.”75

Four and a half miles north of Fox’s Mills and a quarter mile east of Hunter’s Mill in a secluded and very deep micro-valley along Angelico Branch, a local rogue named Charles Adams ran a mill-adjacent grog shop that highlighted the less respectable aspects of these communities.

Hunter’s Mill and its surroundings was more rough and tumble in the 1850s than Fox Mill. The arrival of the railroad brought strangers and outward economic influences into a community that was past its prime. People also made their way to Hunter’s Mill for a variety of lurid reasons. Lethal card games, accusations of prostitution, and heavy drinking shaded the area’s reputation.

Charles Adams only added to the area’s unsavory reputation. Adams attended the secession vote with a drawn pistol to intimidate Unionists. When he was arrested two years later as a Confederate spy, his reputation as “a perfect desperado, drinking and fighting, stabbing and shooting” preceded him. Most ignominiously, his wife of four years divorced him in 1852 because he had seduced and taken up with her sister. Classy stuff.76

In June of 1860, the Commonwealth of Virginia opened a case against Charles Adams. It seems he was operating a grog shop out of his hidden home near Hunter’s Mill. There he retailed “wine, rum, brandy, and whisky” to both slaves and free blacks.77

Rough and rowdy Hunter’s Mill and its more buttoned-up competitor, Fox’s Mill, represent opposite ends of a stream valley corridor that was unserved by major roads along its long axis.

Whether for business or for pleasure, it is a reasonable assumption that desire paths sliced through this critical interval to bring locals to mill centers for a variety of purposes.

An 1856 advertisement posted by Madison C Klein to entice someone to purchase adjoining tracts of land on Difficult Run touted the use of creek-adjacent meadows and fields for fertile farmlands. More importantly, though both of these tracts bounded Hunter’s Mill Road, the selling point for mercantile accessibility was their proximity to Difficult Run itself!

“These lands are undulating, with sufficient bottom for meadows, well watered, having several never failing springs of pure water thereon, and bounded on the west by Difficult Run, on which there are merchant saw-mills of convenient access.”78

This “convenient access” could only mean desire paths or game trails or bridle paths that darted along the creek valley floor itself.

In short, there were unsanctioned, informal roads that cut along Difficult Run enabling residents in the valley between the mills to access either end.

Proof positive comes in dubious fashion in the form of the 1937 Fairfax County aerial survey of the area. Though anachronistic to Civil War studies, the territory between Fox’s Mill and Hunter’s Mill is laced with little white fissures, each a well-worn trail.

One tracks along Difficult Run, another parallels it from the comfort of shade near the treeline. Still other and more prominent paths cross these first two and connect upwards into draws that cup downwards and transition gently into the plateaus above.

In a county that embraced dairy farming after the Civil War, such paths must be questioned.

Did cows or horses or men or deer carve these? When?

Nonetheless, the patterns they exhibit tell a striking story of connectivity. These trails were fascia, connective tissue between meaningful places where weary farmers’ feet and drunken stumbles could have found the path of least resistance to or from home.

Prehistoric Dimension

The presence of numerous prehistoric sites within or adjacent to the critical interval between Fox’s Mill and Hunter’s Mill on Difficult Run adds literal depth to the notion of abundant desire paths facilitating Mosby and his men.

In Virginia, archaeological sites (their whereabouts, and their contents) are considered “sensitive and protected.” However, the existing public record and other less obvious sources point to a rich history of human resource extraction—be it mineral, vegetable, or animal—in Upper Difficult Run.79

Evidence suggests that indigenous people occupied the space dating back as far as 6000 BC. This prolonged timeline bridges sustenance paradigms to encompass two very different land-use strategies. Unsurprisingly, today’s Oakton once hosted seasonal gathering camps which found native people establishing themselves temporarily on local highlands overlooking Difficult Run where they could gather the acorns and nuts that fell from oak, chestnut, and hickory trees. Later advancements in caloric acquisition found the descendants of these first people utilizing floodplains to source or cultivate plants like chenopod in an early attempt at agriculture.

The Difficult Run of this era would have looked very different from the area John Mosby utilized during the Civil War. Fire regimes encouraged the ascension of mast-producing trees and cleared secondary growth to enable both hunting and some agriculture.80

Once established, natives would not have needed a John Underwood to guide them through obscure thickets. Fire would have pre-cleared the brambles. Still, a few truisms of human-landscape interaction are universal. Early human axial relationships found native people cutting across and traveling longitudinally along the same areas of Difficult Run that facilitated these same motions in the 19th century. Thicket or not, the first people to make these moves would surely have found the paths of least resistance up, down, across and through in ways that patterned, formalized, and literally terraformed the earth to create more or less permanent grooves.

Adding complexity to this theory of path genesis is the fact that both the Chain Bridge and Hunter Mill Road were both known indigenous roads that traversed the Potomac River and traced across ridges to intersect in what would become Oakton. It is unlikely that the nexus of these two prehistoric trails had nothing to do with the prominent deposit of highly sought after white quartz on Marbury Road off Hunter’s Mill Road less than a mile east of Difficult Run in its critical interval.

Tool-making stones, creekside foodstuff, forest forage, and game all incentivized prehistoric people to beat trails across the landscape between the future Fox’s Mill and Hunter’s Mill. There is a pedigree—obvious or not—to the bridle paths that laced through the area during the Civil War.

(For more on indigenous roads, see this post.)

Proximity to Federal Lines

If presence of ad hoc roads with intermixed native significance were the only criteria, then it would be difficult to eliminate any of Northern Virginia from consideration as a funnel for Mosby’s forces.

One essential qualifier to the place puzzle at hand is proximity to Federal lines.

First and foremost, John Mosby and his Rangers required cunning routes with which to bypass established Yankee outposts and patrol lines. After the initial success of his raids in early 1863, the wide net cast by Federal forces in western Fairfax County contracted to a more reasonable dimension just west of Fairfax Courthouse.81

Early ambushes along Horsepen Run near Frying Pan and along today’s West Ox Road were overlooked until John Mosby and his men penetrated Fairfax Courthouse and captured General Stoughton. In the aftermath of that raid, Federal lines seemingly acknowledged the unpatrolable nature of Difficult Run by establishing the main line of occupation just to the east on a line stretching from Jermantown up to Flint Hill, Vienna, and Tyson’s Corner beyond.

From this position, heavy contingents of Federal cavalry struck out along major corridors like Hunter Mill Road, Lawyers Road, the Old Ox Road, and the Little River Turnpike. Difficult Run intersects all of these major thoroughfares.

More importantly, the critical interval of the creek stretching between Fox’s Mills and Hunter’s Mill would put John Mosby and his men within a short ride of each of these corridors while providing easy access to the main line of Federal cavalry guarding Fairfax.

The brilliance of the position Mosby occupied on Difficult Run was its relative wealth in interior lines that were unsuitable for the bulky road columns utilized by his pursuers. Operating in single file or in a herd-like cluster, Mosby and his men could dart across fields and forests and outmaneuver Federal units who would arrive at the same place in twice the time.

This process is more than a hypothetical. It’s quite likely an operational model for how Mosby and his men seemingly disappeared at Ox Junction, made contact with yankee pickets at Flint Hill and then dipped into the woods only to cross over Chain Bridge Road at a point north.

Reciprocal proof is available in the form of multiple after-action reports that place Mosby’s Rangers east of Fairfax, near Annandale, and skulking about in the woods of Accotink Creek.

Established on October 1, 1863, Company B of Mosby’s Rangers was created in no small part to hunt into this forward operating area. Its First Lieutenant, Frank Williams, had privileged local knowledge.82

Frank Williams, grew up on four hundred and twenty two acres in Vienna right on the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad just east of Chain Bridge near where the Whole Foods is today.83

An anecdote from James Joseph Williamson in his account of his years riding with John Mosby shines light on the psychogeographic dimension of Frank Williams’ attempts to marry his sense of home with his duties as a Ranger Lieutenant.

“Thursday, October 22—Lieutenant Frank Williams was ordered by Mosby on a scout inside the enemy’s lines in Fairfax. This territory was in close proximity to the Federal capital and well guarded at the time> he selected for his companions John H. Barnes, Robert M. Harrover, Dr. T.E. Stratton and Charles Mason. They struck the carefully guarded Federal picket line along the Vienna and Fairfax Court House road, and under cover of darkness passed through without giving an alarm. They were now in the enemy’s country, but in the vicinity of Williams’ home. Feeling quite safe and anxious to learn all possible of the situation he decided to call upon an old family servant. This old slave was true to his master and the cause of the South. They approached the house about midnight. It was dark and still. They were miles from their comrades, in the midst of a hostile country. Suddenly they rode right into an encampment, not being able to see the tends until they could almost touch them. Slowly and cautiously they withdrew and attempted to reach the colored man by another road. They had proceeded but a short distance when they were met with the command ‘Halt!’ and a volley of musketry at close range. They again had to retreat, but not before Harrower gave the enemy a parting salute from his revolver, the only shot fired by Williams’ party. Being anxious to see the old colored man they made another effort to reach him, and in crossing the Alexandria and Leesburg Railroad another volley was fired at them. Under these conditions they concluded to postpone the visit and strike out across country to Annandale, on the Little River pike….From a position where they had a view of the pike they saw a number of horses grazing; also a body of cavalry not far distant. After consultation they decided to withdraw, secret themselves in the timber, return under cover of night, and make off with as many horses as possible.”

Almost off-hand, Williamson offers valuable proof of Difficult Run’s importance in Mosby forward operations during 1863. In seeking to find his way across “the carefully guarded Federal picket line along the Vienna and Fairfax Court House road” ie: the Chain Bridge Road located on the ridge just above and to the east of the critical interval, Frank Williams solicits the help of Jack Barnes, a man with intimate connections to and knowledge of the section of Difficult Run above Fox’s Lower Mill where the raiding party would slice through Yankee videttes.

The account goes on to describe a failed attempt to outride Federal cavalry on the following day, which led to Williams being unhorsed. After a day spent cutting through the landscape to dip into friendly lines, Williams arrived hatless the next morning at the nearest friendly landmark—Hunter’s Mill at the northern limit of the critical interval of Difficult Run. There he “received a hearty welcome, a good breakfast and a Yankee cap.”84

These places were familiar to Frank Williams. He wove his duty as a Confederate officer into the unique gravity of his home and existing social relationships while falling back on adjacent friendly landscapes when times got tough.

Beginning in October, Mosby and his men struck toward Alexandria on the Little River Turnpike and into Annandale.85 These bold attacks represent an integration of Williams’ place knowledge into command operations and an obvious tying of these territories into the existing adjacent corridor of advantage.

Our critical interval of Difficult Run was three miles from the home in which Frank Williams grew up. In mid-1863, a stiff line of Federal resistance separated Mosby from these happy hunting grounds. Its ultimate utilization speaks to the fact that Mosby was incentivized to find a way to exploit Federal lines in the area nearest Williams’ homes.

Still more intriguing is the notion that our section of Difficult Run provided multiple proven means of ingress and egress for small units of Confederate partisans to slip past Federal lines.

Three obvious corridors of opportunity bridge the line of desire paths along Difficult Run with Confederate objectives east of Hunter’s Mill and Chain Bridge Roads.

- A direct route from Difficult Run up and through modern Miller Road or Samaga Drive offers immediate access to the intersection of Hunter Mill and Chain Bridge Roads. Heavily travelled by Federal forces, John Mosby famously frequented the area as well. At that crossroads, a dominating oak tree rumored to be the inspiration for the place name “Oakton,” was long known as the Mosby Oak, because John Mosby attempted to capture Yankee-born Sully Plantation owner Alexander Haight there on August 29, 1862.86

- Low and slow, Mosby and his men could have ridden through the low profiles of Difficult Run or its many tributaries like Rocky Branch, Piney Branch or Angelico Branch, to achieve a custom, if cumbersome route across Federal lines.

In his poem “The Scout Toward Aldie,” Herman Melville describes the paranoia-inducing combination of dense foliage and broken terrain that made this stretch of the Federal line a nightmare to defend.

“They pass the picket by the pine

And hollow log — a lonesome place;

His horse droop, and pistol clean;

’Tis cocked — kept leveled toward the wood;

Strained vigilance ages his childish face.

Since midnight has that stripling been

Peering for Mosby through the green.”87 - Quickest still, if not less direct, was the isolated avenue provided by the defunct Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire railway. Whether the track was torn up early in the war or during the Antietam Campaign is a matter of some small controversy.88 What’s clear is that the railroad was out of operation and its bed available to other uses by the time Mosby arrived in town. Though slightly out of the way, its path would have taken a direct line to Frank Williams’ father’s property and to the host of hyper-local place knowledge that that spot provided.

Crucially, we know that Mosby Men felt very comfortable operating with impunity on the stretch of railroad bed nearest to Difficult Run by Hunter’s Mill.

During a raid into Falls Church on October 18, 1864, Captain Montjoy of Mosby’s command detected a rabid Unionist blowing a horn to alert the Federal home guard of the Confederate presence. The culprit was the Reverend John D. Read.89

The Rangers took Read and a freed-slave named Frank Brooks captive and summarily executed them by close pistol shot on the tracks of the AL&H Railroad within a few hundred yards of Hunter’s Mill.90

Though Brooks survived to tell the tale, John Read was good and dead. In their guide to Mosby sites in Fairfax County, Charles Mauro and Donald C. Hakenson describe meeting an Oakton old timer who remembered local school children jumping rope to a rhyme about John Read’s demise nearby.

“Isn’t any school

Isn’t any teacher:

Isn’t any church,

Mosby shot the preacher.”91

The larger point is that Mosby and his men obviously utilized corridors immediately east of the critical interval of Difficult Run to slip through Federal lines. Besides terrain and pre-existing path advantages, the Gray Ghost used this particular area because of another obvious fact.

Friendly Control

The proverb of the Reverend John D. Read teaches that proximity to Federal lines could be a problematic proposition for both parties. Any inkling of divided loyalties courted disaster. Rebel partisans faced capture. Unionist civilians faced possible death.

These dynamics lend weight to the theory that Upper Difficult Run was a viable corridor for Confederate partisans. This conclusion is the fruit of a prolonged spatial analysis that was only recently made possible by a wealth of cartographic GUIs, graphic design tools, and digital records.

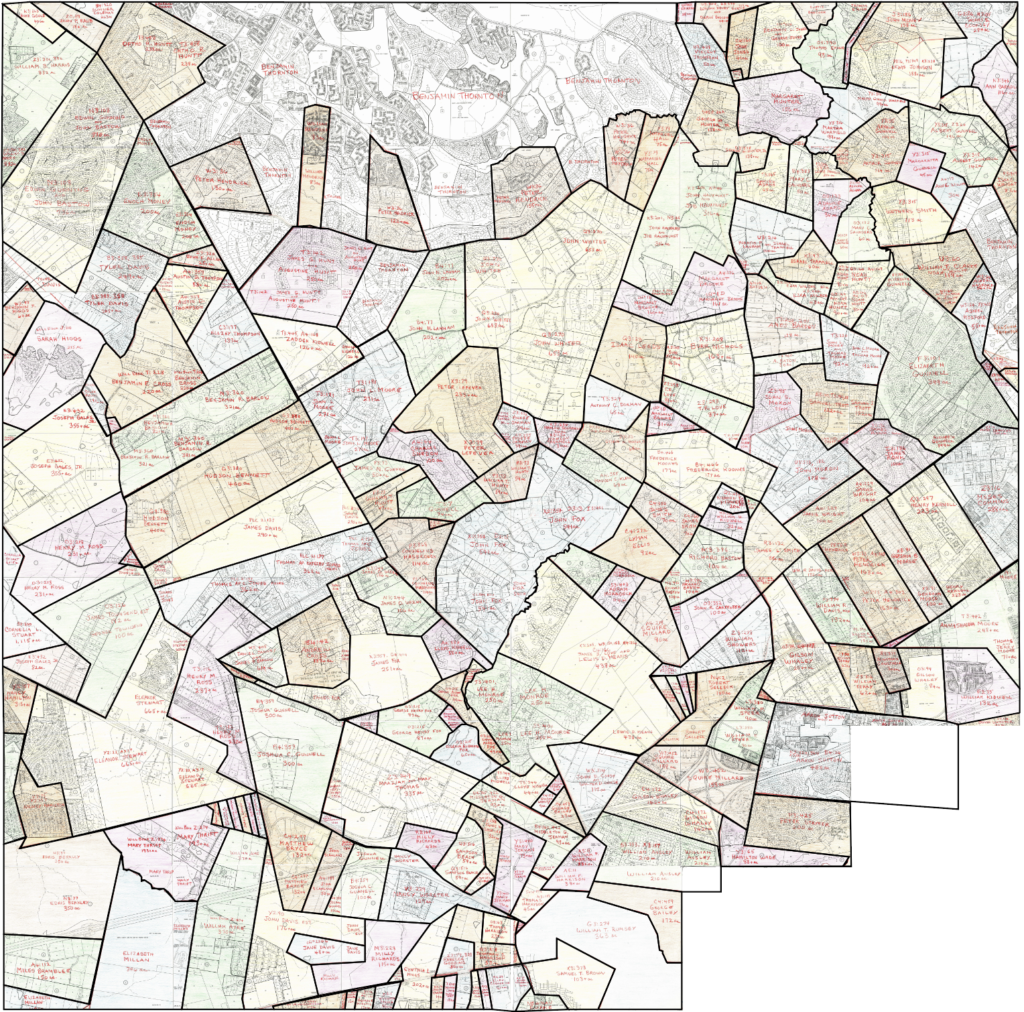

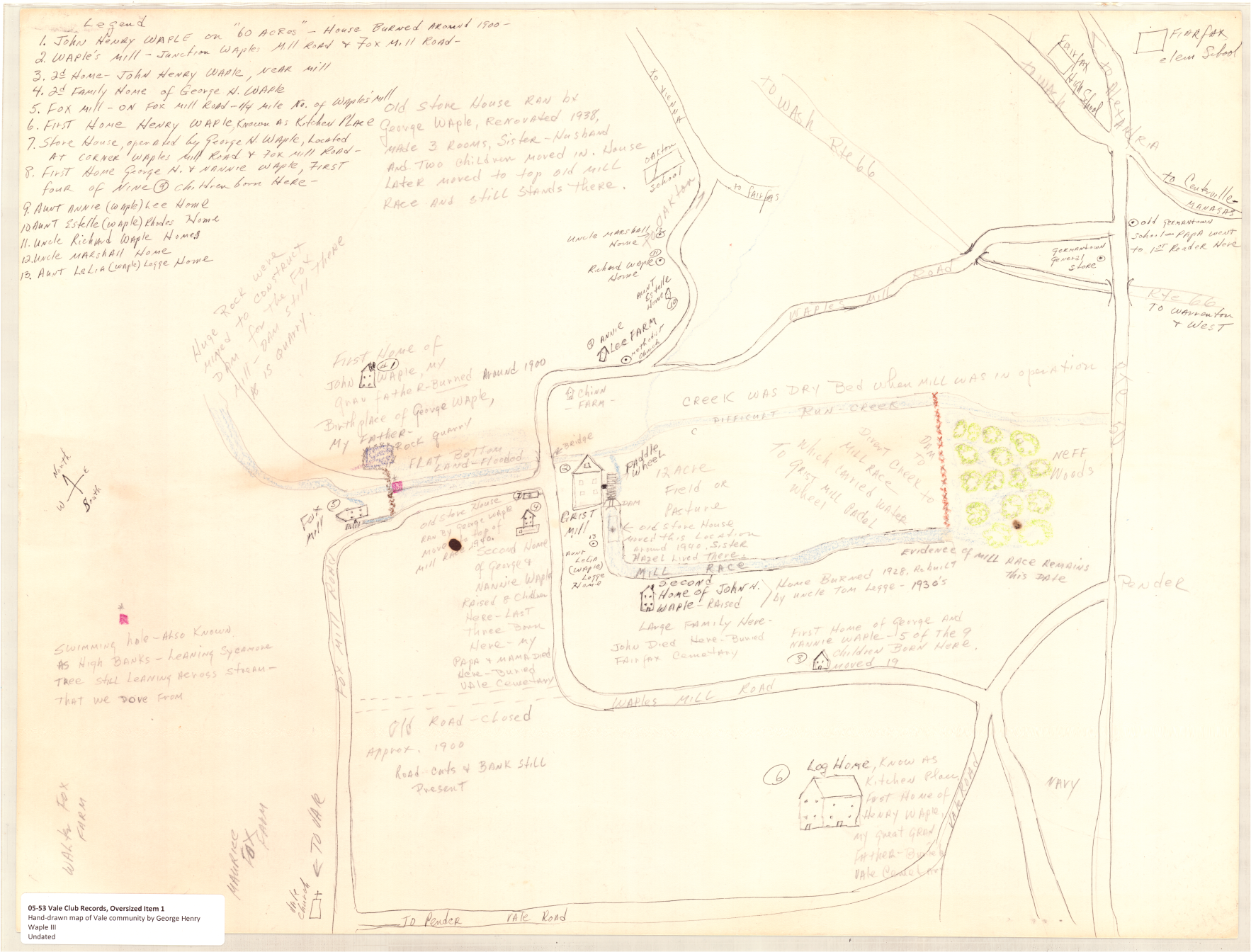

Below is a map that represents many dozens of hours of my time. Its base layer is an 1860s property map that that immensely talented and passionate historian Beth Mitchell painstakingly cobbled together by taking colored pencils to the Fairfax County 1981 Real Property Identification Map.92

The detail is so granular and the map is so large that a single working, zoomable version has never been hosted online. In December of 2022 and January of 2023, I screen-capped every individual panel in or adjacent to Upper Difficult Run, trimmed it, and pieced them together into a single map.

Then I went through this monstrosity and diligently recorded every property owner and the map codes identifying which squares of the map correspond to their holdings. For nine months, I agonized over local genealogy. Ancestry, Family Search, wedding announcements, single-family genealogical monographs in the Historic Society yearbooks, census records, deed books, chancery documents, et cetera. I hit them all more than once.

The prize at the end of this tedious process was the resolution of illusory distortion in the Mitchell 1860 Property Map. These were not discrete parcels. Rather, the property lines represented legal boundaries that blurred and morphed over time to disguise elaborate kinship networks.

Next, I parsed these kinship networks through Fractured Land, Brian A. Conley’s compilation of the 1861 viva voce secession vote.93 This allowed me to stylize individual parcels in either light gray or light blue to indicate the way the owner voted. Then I cross referenced William Page Johnson, Jr.s’ Brothers and Cousins: Confederate Soldiers & Sailors of Fairfax County, VA, as well as the National Soldiers and Sailors Database, and the roster appendices to the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry, 8th Virginia Infantry and 17th Virginia Infantry histories to determine Confederate service.94

This last detail enabled me to deepen shades of gray in instances where property owners both voted for secession and someone in their immediate family (father, son, brother) was in Confederate service.

The results are very intriguing. A deep swath of heavy gray reflecting pro-secession votes and Confederate service cuts through the Difficult Run valley between the Little River Turnpike and Hunter’s Mill. Even more noteworthy is the presence of blue marbled throughout the area.

My built-up map has problems. To wit, I cannot account for tenancy or owner occupation. It’s extremely likely that more Mosby Rangers lived in the area at the time. Specifically Clarke and Saunders, whose descendants later claimed that the two boys, along with their good friend, John N. Gunnell, all left their homes near the intersection of current Fox Mill Road and Stuart Mill Road to join Mosby.95

More noteworthy still is the presence of multiple Unionist votes marbling through the valley. In her contributing chapters to the definitive Fairfax County History, Patricia Hickin claims that “by 1847, some two hundred Northern families, averaging six members to a family had moved into the county.” The end sum of this population influx was that a third of the white male population in Fairfax County was northern-born by the outbreak of the war.96

In some local precincts like Ross’ Store or Sangster’s Station where future Mosby Rangers Frank Fox, Minor Thompson, and Jack Barnes voted to leave the Union, secession was a near-unanimous position.97 This accounts for the massive gray pocket.

However, the splotchy blue along Lawyers Road and around Hunter’s Mill was represented at the polls in Lydecker’s near Vienna where Yankee sentiment was bold enough to rebuke the southern cause and vote against secession.98

Blank spots on the map where the original 1860 property ownership bleeds through without a clear indication of either pro or contra secession sentiment speak to another distortion. A culture of voter intimidation at the secession vote may have stymied accurate representation of northern sympathies.99 Many of the names near the critical interval—Isaac Leeds, Phoebe Carman, John Whited, Richard Bastow, and Frederick Koones were known Yankees.

This last issue raises a more significant question: did anyone of Yankee birth or Unionist inclination remain in the valley during the war? The answer is most likely no.

If political intimidation at the polls was incentive enough not to vote, then the pressure-cooker of anti-yankee violence that emerged in this district of Fairfax County would have been compelling enough to encourage a rapid exit.

A news item from the Alexandria Gazette dated November 9, 1860, details the assault of a man named “Gartrel” who cast a ballot for Abraham Lincoln. The Republican voter was “seized by a party while he was coming out of the Court-house and carried a short distance from the village, where he was blacked completely with printer’s ink, mounted on his horse and started for his house.”100

Many took the hint, including Job and John Hawxhurst—the area’s most prominent Yankee landowners and staunch Quaker Unionists. John became a local delegate to the absentee Unionist government of Virginia from the safety of Union lines.101 Left untended during the war, their mill along Lawyer’s Road at its intersection with Hunter’s Mill Road became a favorite haunt of Mosby guerrillas.102 Along Old Bad Road, the nearby property of their sister’s husband, Isaac Leeds, was most likely abandoned and conceded.

Beginning with John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry, a culture of suspicion heightened. Yet, many Yankees were able to withstand the outbreak of hostilities and remain in semi-occupation of their farmers. That mostly changed with the arrival of the Army of Northern Virginia in August of 1862. Preceding the gray-clad infantry was a cloud of cavalrymen who sought to arrest anyone suspected of harboring anti-Confederate positions. Men like Sully Plantation owner Alexander Haight fled western Fairfax County “by cutting across fields and keeping to seldom-used byways.”103

Two prominent northern-born landowners who lived east of Hunter’s Mill Road between Difficult Run and the Federal lines left the area for the duration of the war. Their testimonies to the Southern Claims Commission chronicle intense material losses and a stiffer sense of urgency connected to their departures.104

In May of 1861, a pro-Union resident of Vienna penned a letter to a friend in New York, in which he described a neighborhood that had passed a threshold from harsh words to violence. “Men are persecuted and threatened with violence and even with hanging for wishing to cling to that government which has protected them in their civil and religious liberty, which has thrown over them and around them a halo of Freedom and prosperity that no other government under heaven has,” wrote B.S. Carpenter.

He went on to describe an attendant mass exodus of Unionists. “Thirty four families left Vienna in two days with what they could hastily gather up and then bid adieu to their homes for which they have toiled to make comfortable and pleasant.”105 In short, the country was quickly emptied of Yankees.

Deeper in Difficult Run, even native Virginians born into deeply-entrenched local families were likely not spared the wrath of their neighbors. John Moore, a descendent of Difficult Run Baptist preacher Jeremiah Moore and owner of the land east of Fox Mill Road immediately across from Bennett Road, voted for Virginia to stay in the Union. This made him the sole Unionist between Lawyers Road and Little River Turnpike in the area of Fox’s Mill.

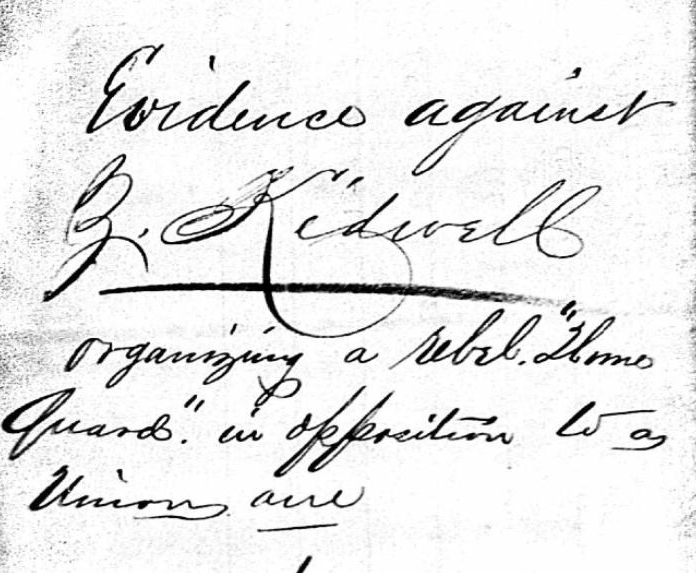

Little is known about the consequences he faced for his vote, but the arrest of his immediately adjacent neighbor, Zadoc Kidwell, for a plan to create a Confederate Home Guard and strike out against Unionists probably did not bode well for Moore. At very least, any thoughts of rendering aid to Federal forces were likely curtailed.106

By voluntary removal or collective coercion, the divided sentiments of April 1861 were well homogenized into pro-Confederate consensus by the time Mosby arrived in Difficult Run. This factor alone would have made the area appealing on a temporary basis, but an undocumented invisibility made it priceless as a Confederate asset.

Invisibility

Whatever wayward Union topographical engineer coined the name “Old Bad Road” as the wartime moniker for today’s Vale Road also initiated a culture of avoidance that cast the Upper Difficult Run Basin as either unusable or undesirable for military application.

John Mosby was able to fashion the area into a reliable forward operating base for Confederate partisan warfare because of abundant desire paths, prehistoric use corridors, close proximity to Federal lines, friendly locals, and a physical condition of invisibility that went far and beyond a simple place name.

The four and a half mile stretch of Difficult Run between Fox’s Mills and Hunter’s Mill was anchored on either end by geographic and man-made obstacles that veiled the broad meadows between behind a scrim of inaccessibility.

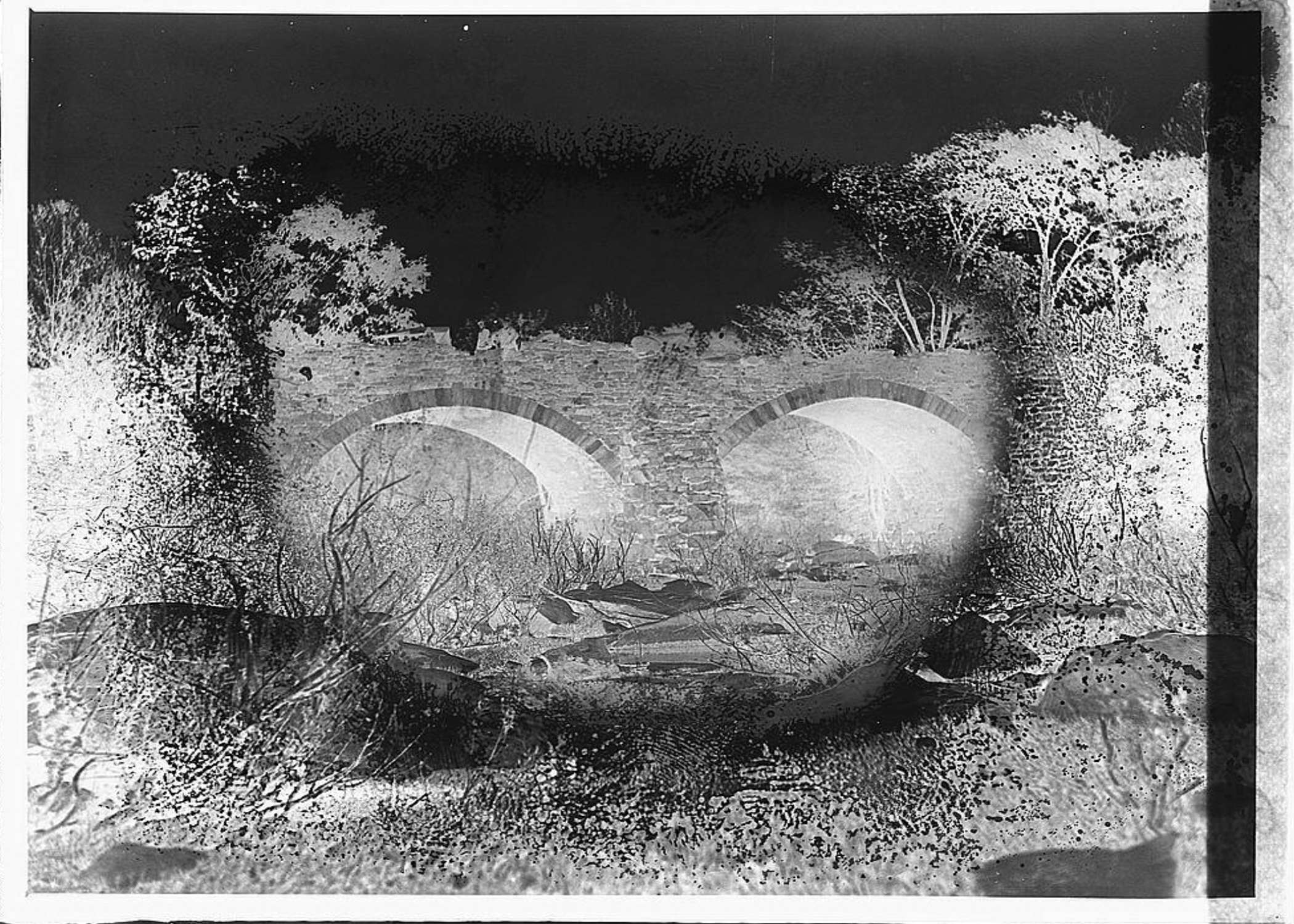

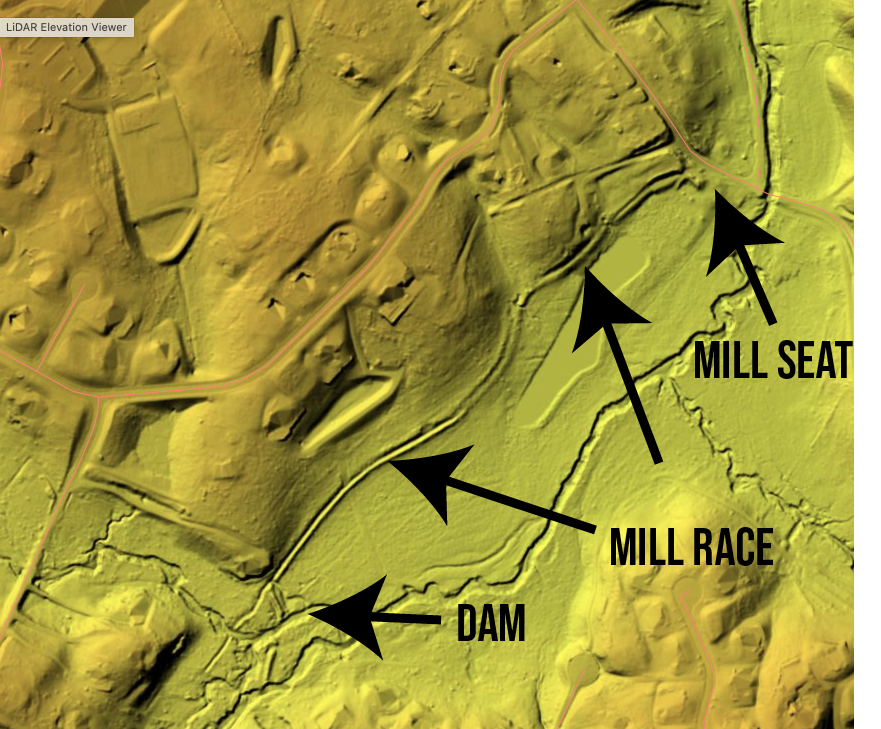

In the early 1980s, Mosby historian Thomas J. Evans and his son set out to pin down the location of “Hidden Valley,” a defile in the area of Hunter’s Mill where Mosby collected captured horses to be reshod and led back to the Bull Run Mountains.

With the help of the son of a Mosby Ranger, the Evans tandem found a micro-valley east of Hunter’s Mill Road where broken horseshoes and other relics suggesting a temporary blacksmithing operation from the mid-nineteenth century remained untouched.107

Hiding a blacksmith and a substantial herd of horses within Federal lines requires a certain confidence. Obviously the place conditions off Cedar Pond provided a certain sense of invisibility. Perhaps this is why the land’s rightful owner, Charles Adams, used the same corner of the Difficult Run Basin to run his illegal grog operation in the years before the war.108

This known Mosby haunt was a half mile west of the location on the AL&H tracks where Mosby Rangers murdered the Reverend Read. Equidistant in the opposite direction was the relative safety of the densely-wooded trees and dramatic terrain surrounding Hawxhurst’s burned out mill.

A road petition from January 1867 sheds light on the obstacles that made this section of the creek terra incognita for Federal forces. The original stretch of Lawyer’s Road running west from Hunter’s Mill Road (ie. The road as it was during the war) made an awkward dogleg to approach the mill that necessarily sat in the narrowest and steepest section of the valley where hydromotive power potential was at its best.

The petition of 1867 sought to “avoid some very steep and rough hills and a bad ford at the old mill site.”109

In the post-war rebuilding boom, the Hawxhurst’s Mill was reconstituted on a slightly different pad just to the north of its original site. However, the existing millpond, millrace, and likely dams retained their original position nestled in the “steep and rough hills” south of the burned-out mill. Unless these features were in a state of utter, unsalvageable disrepair, they would have retained water and created a marshy, impassable morass.

For all intents and purposes, the line of creek just south of Lawyer’s Road—the northern anchor of the critical interval—was impenetrable.

A similar phenomenon occurred on the opposite end of the critical interval at Fox’s Mills. Relying entirely on second hand accounts, Army of the Potomac cartographer created a series of maps of dubious accuracy meant to provide clarity to accounts of the Battle of Chantilly. These maps fail to capture the nuance of the field.

However, one aspect that they do reliably depict is a significant marsh along Difficult Run just east of the Little River Turnpike. Multiple circumstances corroborate the existence of a water obstacle here. First and foremost, Sally Summers Clarke, niece of Frank Fox and granddaughter of Fox Mill heiress Jane Fox describes the dimensions of the Fox millpond as “perhaps a quarter of a mile wide and a half mile long.”110