TL;DR–fear of poverty and hatred of categorical others were powerful root motivators behind the scenes of 19th century sectional conflict.

The summer heat in Fairfax County is oppressive. The glare of the sun pins a person down and the weight of the air holds them there. This goes on for days on end. Weeks sometimes. Forests and fields thrum with teeming masses of unseen cicadas and katydids. Fairfax retreats indoors.

Then one morning things change. Whisps of white in the atmosphere congeal. The air feels fragile. Fluffy white cotton ball clouds grow gray and distended. A playful breeze becomes a feral wind as the skies darken.

Meteorological minutiae fails in favor of folk lore. Poplars and the oaks give final warning. When the bottoms of the leaves flip up to reveal millions of white bellies, the approaching storm is no longer approaching. It is there already, sucking air into its thundering lungs.

In no more than thirty seconds big drops of summer rain drive through the heat and send a bouquet of diffused tar and earth into the heavy air when they sizzle against the scorching asphalt of neighborhood streets.

It is easy to feel invaded when the storms arrive. They seemingly come from elsewhere to attack peaceful domesticity with chaotic atmospheric power. This is an illusion.

The grand squalls that launch off the Blue Ridge and barrel across Loudoun, Fauquier, and Prince William Counties to rattle the windows and howl through the trees of Fairfax owe their potency to close conditions.

Large storms are little more than conglomerations of locally-sourced heat and moisture. On those summer days, every little plant, mud puddle, and dry pond sweats its yield upwards. Transpiration and evaporation at microscale combine and contribute the essential preconditions for storms.

Your neighborhood dew drop becomes gaseous molecules that climb 40,000 feet above the Commonwealth of Virginia where they harden into ice and collide with one another. Every collision creates a charge. The clouds become electric and organize into something lethal. Pockets of current send charged fingers out and down, looking for their reciprocal part. The lightning that strikes the ground arrives in its point of contact because there is a receptive element at that very place. Sometimes the ground itself reaches upwards into the air with its own electrical charge.

This relationship is essential. It takes two to tango, so to speak. Huge, brawny clouds owe their strength, their capacity for violence, to powerful relationships with ultra-small-scale pockets of life.

Grand Abstractions Reign

Lincoln recognized the war it for what it was: the defining storm of our nation’s existence. It roiled on the horizon for a generation until conditions were right and then unleashed its terrible fury on the American landscape and the people that inhabited it.

We know just about everything there is to know about the flashes of white-hot current that reached down from the storm and savaged small sections of America in so many irreparable instants. You need look no further than the battle flags to recall these strikes: Gettysburg, Manassas, Stones River, the Wilderness, Chickamauga. The list goes on.

If you have the right ears, you can still make the thunder peels echoing through the land. Or maybe that’s the bark of another storm?

What we do not know and get further away from knowing every day is how individual obscure corners of the American nation fed the storm, nourished it, surrendered to it, and sent its own energies upwards to summon its vengeance down.

There exists a raft of explanations tied together with justifications that typically appear in the form of ideas. These thoughts were supposedly potent enough to drive otherwise rational men to die and, more importantly for a nation then steeped in the lessons of the ten commandments, kill.

Duty, honor, states’ rights, spirit, justice, freedom, liberty, and equity between men are lovely ideas that are powerful enough to build mighty hosts. Any one of these concepts is sufficient to explain the Spirit of ’61 and the fisticuffs on the Plains of Manassas. Here is your moisture and your heat. The stuff of storms on the horizon.

These abstractions lack a requisite immediacy. Aspirational ideas about identity and philosophy push men to combat, but they are rarely enough to hold them there. Take any private on either side and transport them out of the maw of the Muleshoe or the West Woods or the Slaughter Pen or the Deep Cut or the Widow Tapp’s Farm and ask them why they were there at that moment doing what they were doing. It would be remarkable if their answer was couched in the language of intellectualized rationalizations and not core emotionality.

No flag and no idea suffice to motivate. These events were savage. The sheer aggression and cruelty of this war was raw and personal. You and ninety-nine of your boyhood friends stand half a football field away from another tight knit social group and bore fist-sized exits wounds through one another until someone relents or everyone falls.

What electrical impulse drew up from the land and into the bodies of its sons to enable the storm to strike down so many for so long?

The answers are dim. In part because the scale of the horror of our Civil War shrouded its survivors in a glory that prevented honesty. A magnificent fabric of men could not be saddled with the hard and ugly truth that they entered the war from a position of anything other than absolute moral rigor.

New evidence emerges. The puzzle reconfigures. In Difficult Run in Fairfax County, Virginia, on the eve of the Civil War, men lived in fear. They were afraid of poverty. There was a true terror that the future would be less bountiful than what they imagined their ancestral past had been. Worse, these people connected poverty to a deeper fear of enslavement.

This fear was rooted in the presence of an “other,” the Yankee farmers who settled in that section over the previous twenty years and lived amongst these third and fourth generation Virginians. People who sounded or looked or behaved or prayed or feasted or farmed in ways strange to the traditional Virginia sensibility were instruments of this pervasive fear. By their very existence, their unrelenting nature, their moral clarity, and their prosperity, these Yankees provided another crucial spark: hate.

When these insecurities merged and the prevailing wisdom posited that the men they hated where preparing to subjugate them into the world of poverty they most feared, the church-going, tax-paying, Whig-voting men of Difficult Run felt they had no choice but to secede.

The rest is history.

They Came to Take from the Land

Humans came to Difficult Run to extract resources from the earth. This is the first and most important premise. This pattern predates the arrival of English colonists by thousands of years.[1] Spruce and hemlock forests disappeared in the wake of the last ice age to make way for oak, chestnut, and hickory trees that sustained native Algonquins with gathered calories.[2] Seams of abundant white quartz along old ridge roads made for valuable trade goods along the Potomac—a river named in native tongue for its propensity to host market exchanges. The many deer that still haunt the woods here represented valuable sustenance. Eventually, the quarter mile wide floodplains that shouldered off Difficult Run, Little Difficult Run, Angelico Branch and Piney Branch would have made excellent laboratories for first forays into designed agriculture.[3]

A variety of motivations brought prehistoric humans here: subsistence, trade, and tribute for kings. The governing principle ruling all subsequent social bonds and common values sprouted from one central truth—people survived by building economies from ecologies.

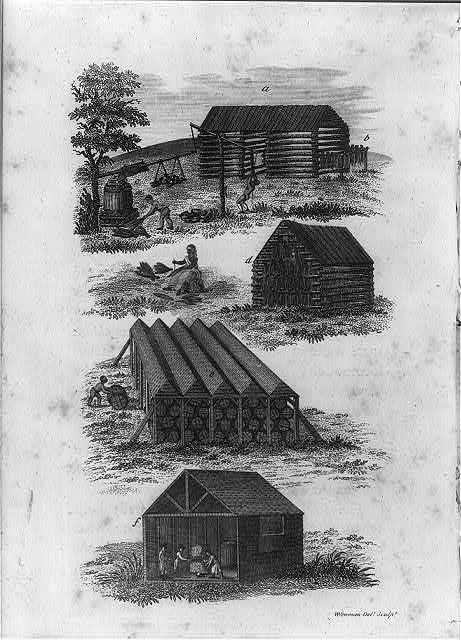

The English, too, came to take from the land. Their efforts were both more brazen and more myopic than those of their native predecessors. What indigenous people stewarded for millennia out of necessity, the English devoured within a generation.

A “frontier mentality” prevailed beneath the overarching framework of a trans-Atlantic trade that hungered for cash crops.[4]

For first arrivals, the only settlement model that made any sense was chiefly economic. Produce as much of the crop that brought the most money at market at whatever cost to the land. There was, they thought, going to be more land, forever. Endless unclaimed forests awaited the armed English transplant. Everything that became Fairfax County sprouted from this original conceit. The lowland rolling roads, the Alexandria wharves, the many churches and their generous glebes, the court houses, and the ordinaries that welcomed their many litigants on court day—this social infrastructure was an outcropping from a microeconomy premised on coaxing as much tobacco leaf as possible from the soil.

The looming disaster is obvious after the fact. Each planting season leached unreplenishable nitrates from the soil. Farms set in sandy bottom lands and stripped of trees lost inches of soil every winter. Avery Odelle Craven estimated that the height of tobacco planting in Northern Virginia found the Potomac River carrying away as much as four hundred pounds of soil from every acre in its drainage basin each year.[5]

These numbers spell disaster writ large. For planters of the age, cost mattered less than profit. Returns on tobacco created a very real sense of opportunity.

In an important sense, the first plantations that leached the soils of Virginia’s tidewater were less about hardscrabble homesteading and more about ferocious desperation. Strip these ecological-economic circuits of their mythos and you’ll see venues where England’s second sons and slum-born servants had a rare chance to escape the terms of their birth.

The first century of Virginia can be read thus as a massive jailbreak from the stagnation and stricture of the Elizabethan Age.

Heartier escapees cut loose from the Potomac after a few seasons once virgin soil began to wilt against the demands of its ongoing prima nocta beneath the English plow. Others stayed and followed a patchwork of lesser land in search of yields that would never match that first season.[6]

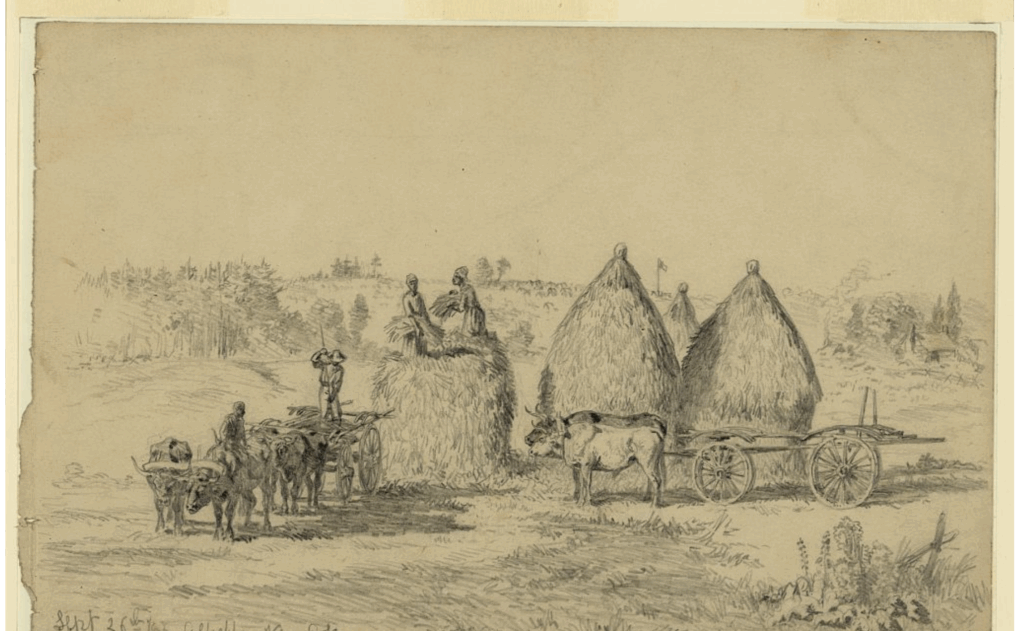

The revolution came. America became America. Soon, conflict moved to the European continent. Rolling roads cut into the earth to facilitate tobacco exports found second life as conduits for Fairfax-grown wheat—a crop that thrived on well-used land.[7]

Another boom came and times were high again. Then peace came to Europe. Plows beat from swords of the Napoleonic Wars tilled wheat in French and Spanish and German fields again. When grain prices in Virginia stabilized, the good times were gone for good.

What ensued was a season of harsh realism. Boundless opportunity and easy money in agriculture disappeared. In its place, the grand art of capitalism flourished. The gentleman farmer was a losing proposition. Instead, the millers, shipping agents, railroad and turnpike boosters, bondsmen—antebellum finance men, one and all—took over.

Wealth and its attendant status were no longer grown in Fairfax County, but acquired by implementing creative ways of processing, transporting and selling another’s crop cheaper, better, and faster.

Meanwhile, Fairfax’s farms fell into disrepair and the grain interests in Alexandria sent their tendrils farther afield to find new suppliers in Fauquier, Loudoun, and the Shenandoah beyond.

The death knell of first Fairfax came in 1837 when a national banking crisis produced a liquidity shortage. Scarce money spelled ruin for short-on-luck farmers who borrowed in spring to float their operation until harvest.

Many more left. From 1810 to 1840, the population of Fairfax County fell by thirty two percent.[8] Land prices plummeted in deference to the ruined condition of the soil. The writing was on the wall for Virginians: leave or be left behind.

The Yankees Arrive

Meanwhile, all was not well in Upstate New York. If Virginians felt the crush of diminished returns and darkening prospects, young farmers of the Empire State felt equally vulnerable for very different reasons.

Farmers of the Hudson Valley planted for longevity. Shorter growing seasons and soil unsuitable for tobacco encouraged early forays into crop rotation and cover methods that nurtured soils. Early sustainability efforts provided a sense of stability to established farmers while simultaneously kneecapping young men who aspired to farms of their own.

In the mid-19th century, an acre of land in Dutchess or Ulster County, New York was worth between forty and seventy dollars.[9] Few could afford to enter this real estate market as it was. Families that rented farms were subject to further shock when previously lenient landlords refused to absorb the full shock of the 1837 financial crisis. In 1839, rent hikes and cash calls for outstanding debts stoked a frenzy along the Hudson. The Anti-Rent Wars, as they came to be known, featured disgruntled farmers who obscured their identity in “Indian” costumes while they marauded through the landscape tarring and feathering landlords and their agents.[10]

The outcome was not different from the agricultural crisis in Fairfax: many who couldn’t eke out a winning hand chose to leave. In the spring of 1840, fifty-six such families from Dutchess County, New York arrived en masse in Fairfax County.[11]

What could go wrong? Land was cheap. Ruined parcels sold for between five and fifteen dollars an acre. Proximity to the Federal City ensured a ready market for crops. Competition was low and the growing season down south was long.

A chorus of local southern voices greeted the northern interlopers with open arms and round applause. “The Yankees are doing wonders,” wrote one commentator.[12] Agricultural reform was a quickly growing pet project of numerous Virginians who wisely tied their state’s future prosperity to near term efforts to reclaim the soil.

With the arrival of over one thousand Yankees in the ensuing ten years, Fairfax was primed for large-scale agricultural reform. The New Yorkers brought new crops, rotation strategies, deep plows, and dairy farming to Fairfax County. Their skills and knowledge represented a once-in-a-generation opportunity to restore the convective relationship between ecology and economy.

Perhaps there is an alternate universe where the Virginia farmer saw the error of his ways and accepted the gracious wisdom of his Yankee neighbors. Together, they forged a prosperous and stable Fairfax County that served as a shining example of regional collaboration that averted civil war and laid the foundations for a present-day American utopia.

Unfortunately, that’s not the way our world works. Equal resources and unequal ability extrapolated over the span of two decades will result in a massive inequality of returns.

In Fairfax County between 1840 and 1860, one group stagnated and another grew ascendant. Inhospitable farming conditions and anemic markets fostered an evolutionary crucible. It was a red queen paradigm. Every family in Fairfax County had to run just to stay in place. The race was one premised on advanced agricultural precepts. Yankee-born farmers had been running this particular race since childhood. Their Virginia-born neighbors and competitors never really learned how to run.

If the disparity wasn’t obvious in the moment, its tell-tale traces have stained the historical record. The effect of diminishing prospects and lowered status on the Virginia psychology screams out in the ongoing cycles of seasonal debt and court records for spurts of drunkenness and sometimes murderous violence.[13] Both of which were almost exclusively southern pastimes. The predominantly-Quaker New York Yankees are scantly represented in debt suits or court cases pertaining to violence and drink. It would seem they were busy improving their property and buying up local infrastructure.[14]

One of the biggest remaining questions about Fairfax County in the lead up to the Civil War is whether local civility or bipartisan national media frayed first. What is certain is that the 1850s found Fairfax County hosting a budding culture war.

Yankee success behind the plow inspired a raft of nationally-distributed literature enlisting the New Yorkers of Fairfax County as the vanguard of the free labor movement. More than a critique of slavery and slaves, the dialogue indicted slave owners and beneficiaries as participants in an exploitative system that encroached on the rights of their African slaves while infantilizing their owners.

In a series of high-profile reports from Virginia, partisan authors excoriated the ignorance and indolence of white southerners whose want to of initiative and knowledge created a situation that only the Yankee could fix. “There is no place in the United States where God has done so much and man so little,” wrote one such chronicler.[15] Virginia-born Quaker Samuel Janney dug the knife in deeper in the pages of the Richmond Whig where his lengthy jeremiad “The Yankees in Fairfax County, Virginia by a Virginian” first appeared.

Janney described Virginia as such, “Her fields exhausted and lying waste—many of her towns and villages exhibiting the appearance of premature decay; her population retreating; her school system wretchedly defective; and a large proportion of her white inhabitants in a condition of ignorance and degradation.” All of which Janney laid at the feet of young Virginians who would rather spend their time “lounging about taverns, going to races or cock-fighting, or other places of amusement.”[16]

This discourse surely strained the bounds of civility and Christian behavior. Once eroded, the benefit of the doubt was replaced with a presumption of slight that seeded an atmosphere of contention and bitterness. A patchwork of neighbors divided itself into two groups: us and them.

One anecdote demonstrates the easy pettiness with which the smallest social infraction could taint a relationship and entrench stereotypes. In the 20th century, Sally Summers Clarke wrote a memoir describing her childhood at Fox’s Mills where her father was superintendent. She recalls the very moment her father soured on Yankees.

“I particularly remember one New York family by the name of Hammond. They bought land near us. Father heard that they needed some tools to fix their house with. After breakfast one morning he went over to the Hammond’s with the tools. They were just sitting down to breakfast when father came. Instead of inviting father to sit down and eat with them they simply sat down and ate in silence. Father was deeply offended. He took his hat and left as soon as possible. The Hammonds meant no offense in not inviting father to their breakfast table. It was just the way they had been raised. But father felt that the Hammonds were guilty of the greatest breach of Virginia hospitality. No one in Virginia high or low, rich or poor, but what was invited to eat when in a neighbor’s home at meal time.”[17]

In the butterfly theory of social conflict, a bruised ego is enough to start a war. While we’re searching for the tangible on Difficult Run, it’s tough to argue that enough insults printed in agricultural journals or fauxpas committed over breakfast could ever boil over to anything more than ill will. These many words, however potent, did not make a civil war, but the calumny and mistrust they encouraged removed all elasticity from the ordinarily pliable socius of Fairfax County.

Long after the war, John Mosby himself wrote that “our civilization is a thin coat of varnish.”[18] Accumulated insults cracked this veneer revealing unbridgeable fault lines that crackled with the primal energy of Fairfax County’s deepest fears.

Slipping Into Slavery

Slavery really did a number on these people’s heads. A whole circuitry of anxieties emanated outwards from the peculiar institution.

Virginia history is laced with instances of panic in which all levels of white society mustered a cohesive kinetic response to uprisings of indigenous or African-descended people against the dominant socio-economic framework. Events like Bacon’s Rebellion and Nat Turner’s Uprising carved through the surface matter of Ol’ Virginny and revealed forever the flickering jack o’ lantern glow of paranoia that broods wherever systemic inequity produces reciprocal violence.

This first fear is pronounced and well known. The second fear is more prominent and less-spoken still.

A society that enshrines the condition of slavery similarly encodes the universal concept of slavery. All citizens of slave states possessing an iota of self-awareness could summon—consciously or not—a scenario in which they too were enslaved.

Southern intellectuals fell over themselves trying to legitimize the strict boundaries of slavery as a righteous and race-based category. Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens achieved the most crystalline version of this foundational theory in his “Cornerstone Speech” of March 1861.

“With us, all of the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law,” Stephens wrote. “Not so with the negro. Subordination is his place. He, by nature or by the curse against Canaan, is fitted for that condition which he occupies in our system.”[19]

In a speech delivered before the U.S. Senate and reprinted for all Fairfax readers in the Alexandria Gazette in 1858, South Carolina’s James Henry Hammond braided the all-important notion of the African-descended slaves’ natural subservience within the framework of a South that took care of its own. Hammond appealed to the teaming masses of white labor beneath the Mason-Dixon when he accused the North of essentially enslaving its white laborers under the guise of free-labor. The rhetorical device was clear: without racially-determined slavery, the lower whites would be the lowest rung in the social hierarchy. Everyone who witnessed the slavery arrangement from within the South could have understood those terms.[20]

The mask of stalwart solidarity between whites slipped further and further from the face of Southern society in influential readings reserved for the studies of learned, wealthy, and prominent men of the slave system who could afford both education and leisure time in which to read. In 1856, Prince William County’s beloved son, George Fitzhugh, printed his pro-slavery missive Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters. Diving into Aristotelean logic for the reenforcing benefit of his parlored readership, Fitzhugh championed the socialism of subjugation and rebuked the anarchy of raw liberty in favor of this simple calculation: “it is the duty of society to enslave the weak.”[21]

One hundred years later, LBJ book-ended this thought tunnel with an observation about the southern electorate, in which the hard-scrabble whites asserted their identity by locating themselves above African-Americans in the social hierarchy. “If you can convince the lowest man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket,” said LBJ.

At Frying Pan in western Fairfax County, these threads wove together in an eerie paradox that unfolded over the decades preceding the Civil War. In 1840, that Baptist church had nearly thirty African-American members.[22] After John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry, Frying Pan was one of the first areas to organize a night patrol against marauding slaves.[23]

What a confusing construction: the enslaved apparently possessed souls that deserved full salvation beneath the equal eye of a divine savior who knew no caveats of race, but the fellowship that carried this covenant calcified against the fear of these same slaves hacking their masters to death in the still of night. What was advertised as a divinely-ordained hierarchy of humanity was seemingly afflicted with core terrors that questioned the entire proposition.

The cartwheeling contradictions manifest in the actions of the Frying Pan Meeting House express best the desperation with which white thought in Difficult Run negotiated its critical vulnerabilities.

This Baptist sphere nurtured many a Mosby man in the decades before the war. Turleys, Hutchisons, Wrenns, Lees, and Foxs all attended church there. What those meetings instilled in their congregants was a distillation of ideas formulated by the area’s preeminent theologian, Jeremiah Moore.

His Baptist faith reflected a typically American contrarianism. Moore began preaching at a time when Virginia had a state church and all clergy were required to be licensed, a process that ensured orthodoxy. Jeremiah Moore was more interested in a republican faith with fewer boundaries between man and the divine. His religious practice was both inherently spiritual and political. Moore suffered for these beliefs. He was arrested numerous times for preaching without a license.

After the Revolution, Jeremiah Moore established his church at “Difficult” where he espoused a rugged, homespun spirituality that was at odds with the forever-looming menace of state power. In an 1800 letter to Thomas Jefferson, Moore articulated an important pillar of his worldview where class, power, and state authority collided.

“And of course,” Moore wrote Jefferson, “to be born poor in Virginia is to be born a Slave.”[24]

The Difficult Run basin that Moore and his students shepherded was saturated by fear of a dual menace: the powerful hegemonic interests of authoritative elites and the omnipresent threat of slave revolt. These twin pillars of threat created a pocket of thought where men had to safeguard their fortunes and their homes from ever-imminent danger.

The very scenario they had been preconditioned to fear emerged over three successive autumns just two years before the war.

In September and October of 1857, a banking crisis in New York quickly spread its contagion down the eastern seaboard. What began as a halt in specie withdrawals became a general run of bank failures from Portland, Maine to Richmond, Virginia. Credit that was so vital to farming interests in Fairfax County evaporated. The run came at an inopportune interval for local farmers. The bubble popped during the annual wheat harvest when sale of crops was expected to inject valuable liquidity into the local microeconomy. What wheat sales occurred in Alexandria in the Fall of 1857 were based on flagging prices that had dropped as much as 36% since July.[25]

For the umpteenth time, enslaving poverty was knocking on the door. Recovery was slow coming. Fairfax County’s economy was still in a place of raw vulnerability in October of 1859 when news filtered in that an abolitionist briefly seized the Federal arsenal at Harpers’ Ferry some forty miles west. Fairfax was dangerously close to a potent attempt at inciting a general uprising of slaves. New old fears joined the press of imminent poverty.

On October 22, 1859, the Alexandria Gazette reprinted a nightmarish scenario first published in a New York paper: “We have no doubt that it was Brown’s deliberate intention to use the arms which he had brought from Kansas for his treasonable purpose: that he calculated upon seizing the United States arsenal, and thus supply the slaves of Virginia and Maryland with weapons and ammunition, in the hope that they would flock to his standard in thousands.” More importantly, the “bloodshed and anarchy” that John Brown designed to unleash on Virginia had been literally and metaphorically supported by numerous Yankee benefactors.[26]

Here, finally, was a situation that touched both terminals on the vast underground battery of fear and anxiety that Fairfax’s slave society fed for a century prior. This was proof positive that the Yankee neighbors harbored menace in their hearts and that subjugation of the southern people by physical or deliberate force was just a prelude to enslavement. The charge that came off this dawning conceptual picture was strong.

Night patrols formed. Militias mustered. The anti-Yankee hostility was palpable. At least one northerner felt inspired to take out a full advertisement in the Fairfax News where he declared his unwavering loyalty to the southern cause and its peculiar institution.[27]

Shortly after Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860, a man named Gartrel who had the temerity to admit he voted for Old Abe was blackened completely in printer’s ink at Fairfax Court House and sent on his way.[28]

The lead up to the vote for secession in 1861 was laden with overt threats of violence by Southerners. Thomas Moore, a grandson of preacher Jeremiah Moore, famously confronted local Yankees with an ultimatum: cancel their subscriptions to the New York Tribune or get out!

WHY?

The war was a horror in Fairfax County. No one, Yankee or Rebel, won. Both armies ate the ecology in equal measure and denuded the economic prospects of Fairfax County for a generation to come. Poverty and alcoholism ran rampant after Appomattox. Once proud Yankee farms lay in ruins and much of the flower of Fairfax’s southern society lay a-mouldering in the grave. Brave charges under proud banners took more from these people than any slave revolt ever had. Too many of the survivors wore pinned up sleeves where a plow hand or sturdy leg should have been.

Today, we’re one hundred and sixty years into a prolonged dickering match about the merits of the impulses that fostered this destruction. Streaked in bad faith, misinformation, and a wicked sunk cost fallacy that often prevents critical thinking, attempting to answer the question “was it worth it?” feels like a foolish exercise. We’re left instead to ask, simply: why?

There is a tendency to lapse into the pretensions of the “preventable war” theory, by which we are supposed to believe that a single generation of irrational Americans surrendered the onus of compromise in favor of violence. One glance at our own time provides an interesting corollary: conflict is a group effort, nurtured by many generations and contextualized in deep patterns of thought and deed that mark every level of the American scene with its striations. In these spaces, accusations are common and accountability is scarce.

Some Southerners in the pre-war space accused abolitionists of “longing for the apocalyptic moment.”[29] If true, the immanentizing effort to foster a lifting of the veil was also a Southern impulse.

Ecological fragility, economic volatility, social fractures, threats of violence—these shared pathways were not so much manufactured in the 1840s and 1850s as they were unconsciously reflected. Two hundred years of unsustainable agriculture, irresponsible banking, boosterism, and countervailing pride created a pocket of contradictions woven in combative language that encouraged conflict.

The collision of peoples that occurred in Fairfax County in the years before the war was but one critical charging spark in a pre-existing storm developed from the anxieties of many previous generations. Sensing a coming front, Virginians—Yankee-born or southern-bred—agitated towards sectional crisis through a mode of self-interest that precluded calming collaboration.

Compromise, change, forgiveness, and communication premised on equity were not strong suits of either group. However gifted these people were as farmers or sportsmen, retrospect finds them wanting entirely for the very skills that make for lasting prosperity. Fear of poverty and hatred of others braided together as both groups did whatever necessary to fashion structures of power and implements of control that assured they and theirs would do well and would not have to deviate too far from the assumptions and prejudices of their own in-group. Sound familiar?

In 1851, a broad cross-section of Fairfax County (embracing a plurality of both northern and southern identity) threw its weight behind the Whig Party. Everyone could agree that tariffs and infrastructure—two policies that protected and improved the interior sphere against outside influences–were the path forward for Fairfax.

Exposed to the cunning rhetoric of grand narratives posited by distant journalists whose lone interaction with Fairfax County itself came in a series of unidirectional broadcasts delivered via ink splatter, simmering fear and hatred at the neighborhood level oozed a solvent of self-righteousness that ate through any and all bonds of affection.

By 1861, the broadcloth of Fairfax society had ripped and contracted. Many of the same men who had found fellowship as Whig delegates in 1851 were so thoroughly convinced of the fragility of their future and the imminent erasure of their past that they cast votes to cleave apart the country they had worked so hard to cobble together.

The story of the road to secession in Fairfax County is a hyper specific drama about the collapse of local systems against the weight of the ecological, economic, social, and psychological demands of its people. It is also, unfortunately, a universal human story retold in broad stroke duplicate wherever neighboring people see, act, and earn differently than their neighbors.

Our species has a tragic quirk that finds us ducking time and time again into the easy and temporary solace of adversarial arrangements when we should be investing in the rough, but ultimately rewarding pursuit of coexistence. This is truly the old bad road at the heart of the human journey.

If we’re lucky enough to realize in the moment what horrors our local hatreds are feeding, we are often too late to convince our neighbors of such.

Old Fairfax learned this lesson the hard way. Only when the storm and its terrible swift sword of lightning and wind leveled the pre-war world did the accumulated charge of so much spite and ill-will dissipate. Temporarily, at least.

[1] Craig, John, Grace Karis, Susan Leigh, Bonnie Owen and Darlene Williamson, editors. Vale History: From Money’s Corner Through Difficult,” 1991-1995. Fox Mill Communities Preservation Association History Committee. Joy S. Starr Collection on Vale History. Collection 06-18. Virginia Room. Fairfax County Library. Page 5-6—now verboten, the 1990s found local historians disclosing archaeological sites and their specific locations into public record. The earliest known site in “Vale” dates back as early as 6000BC.

[2] Pettitt, Alisa. “Virginia Indian History at Riverbend Park.” Fairfax County Government. Accessed 12/24/24. https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/parks/sites/parks/files/assets/documents/naturalcultural/archaeology/archaeology-first-virginians-riverbend-park.pdf

[3] Smith, Bruce D. “The Cultural Context of Plant Domestication in Eastern North America.” Current Anthropology 52, no. S4 (2011): S471-84. https://doi.org/10.1086/659645

[4] Craven, Avery Odelle. Soil Exhaustion as a Factor in the Agricultural History of Virginia and Maryland, 1606-1860. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006. P. 19-20 “Frontier communities are, by their very nature, notorious exhausters of their soils. The wants and standards of living of such communitites have been developed in older economic regions and they make demands upon the newer sections that cannot be met from normal returns.”

[5] Craven, Avery Odelle. Soil Exhaustion as a Factor in the Agricultural History of Virginia and Maryland, 1606-1860. P. 28.

[6] Ibid 32. Craven sites two seasons of maximum planting potential and a total of four very good seasons before the soil was permanently depleted beyond tobacco production.

[7] Crowl, Heather K. “A History of Roads in Fairfax County, Virginia: 1608-1840. Masters Thesis, (American University, 2002). P. 46.

[8] Netherton, Nan, Donald Sweig, Janice Artemel, Patricia Hickin, and Patrick Reed. Fairfax County, Virginia: A History. Fairfax: Fairfax County Board of Supervisors, 1978. P. 134.

[9] Ibid p. 256.

[10] Huston, Reeve. “The Parties and ‘The People’: The New York Anti-Rent Wars and the Contours of Jacksonian Politics.” Journal of the Early Republic 20, no. 2 (2000): 241–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/3124703.

[11] Abbott, Richard H. “Yankee Farmers in Northern Virginia, 1840-1860.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 76, no. 1 (1968): 56-63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4247368 p. 2

[12] Ibid 4.

[13] Charles Adams’ routine appearances before the county court and the stabbing death of Moses Williams at Hunter’s Mill in 1857 all come to mind. Beach, Georgina. “A Game of Cards At Hunter’s Mill.” HSFC Yearbook 24 (1993-1994): 106-130. https://archives.org/details/yearbook-volume-24-1993-1994/ This quote from a 1918 interview of a blacksmith on Difficult Run rings particularly true: “The conversation turning on ancient taverns and old preachers, the Rambler touched a spring in the old blacksmith’s mind and he let himself out with great earnestness. He said that the cause of the upset of so many of the old families was whisky! Whisky! Whisky! ‘The sons of the rich men wouldn’t work, but they would drink,’ and he gave the Rambler a long list of the sons of men of property who dissipaded their wealth and died poor because of whisky.” “The Rambler Writes of Old Families Living Near Forestville, VA.” Sunday Star. June 2, 1918. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ndnp/dlc/batch_dlc_gonzo_ver01/data/sn83045462/00280658388/1918060201/0488.pdf

[14] Evans, D’anne A. The Story of Oakton, Virginia: 1758—1990. Oakton: The Optimist Club of Oakton, 1991. Pg. 26-27. The Hawxhurst Brothers’ purchase of Col. Broadwater’s old mill on Difficult Run in the early-1850s was one of the most quietly provocative events of the decade in western Fairfax County.

[15] Abbott, Richard H. “Yankee Farmers in Northern Virginia, 1840-1860.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 76, no. 1 (1968): 56-63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4247368 p. 5

[16] Janney, Samuel. “The Yankees in Fairfax County, Virginia by a Virginian.” Baltimore: Snodgrass & Wehrly, 1845. https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/may864316

[17] Milliken, Ralph LeRoy. Then We Came to California: A Biography of Sarah Summers Clarke. Merced: Merced Express, 1938. Https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015041065445. Pg. 6.

[18] Seipel, Kevin H. Rebel. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983. P. 254.

[19] Stephens, Alexander. “Cornerstone Speech.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed 4/12/25. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/cornerstone-speech

[20] “Speech of Senator Hammond, of S.C.” Alexandria Gazette. March 15, 1858. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn85025007/1858-03-15/ed-1/?sp=2&q=mudsill&r=0.147%2C0.031%2C0.524%2C0.323%2C0&st=pdf

[21] Fitzhugh, George. Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters. Published in God’s cuttiest Amazon.com provisioned public domain reprint. Citation in question can be found in Chapter XIX: “Protection, and Charity, to the Weak,” if you can find a copy created by humans for humans.

[22] Netherton, Nan, Donald Sweig, Janice Artemel, Patricia Hickin, and Patrick Reed. Fairfax County, Virginia: A History. Fairfax: Fairfax County Board of Supervisors, 1978. P. 288.

[23] Ibid p. 315.

[24] Moore, Jeremiah. “To Thomas Jefferson From Jeremiah Moore, 12 July 1800.” National Archives. Accessed 1/15/24. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-32-02-0036

[25] “Decline in Flour.” Alexandria Gazette. October 6, 1857. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn85025007/1857-10-06/ed-1/?sp=2&st=pdf&r=0.172%2C1.204%2C0.485%2C0.255%2C0

[26] “Mad Brown’s Insurrection.” Alexandria Gazette. October 22, 1859. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn85025007/1859-10-22/ed-1/?sp=2&q=john+brown&st=pdf&r=0.431,0.312,0.31,0.31,0

[27] Riker, Alfred. “To the Public.” Alexandria Gazette. December 29, 1959. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1859-12-29/ed-1/seq-2/#date1=1855&index=6&date2=1861&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&words=Fairfax+News&proxdistance=5&state=District+of+Columbia&rows=20&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=fairfax+news&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=5

[28] “Excitement at Fairfax Court House.” Alexandria Gazette. November 9, 1860. Page. 3, Column 2.

[29] Blight, David W. American Oracle. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011. P. 70.

Leave a Reply